New Experiments in Art and Technology (NEAT), the latest exhibit from the Contemporary Jewish Museum’s Chief Curator Renny Pritikin (with help from exhibition artist Paolo Salvagione), brings together three generations of Bay Area artists bridging the tricky and much-maligned gap between high tech and aesthetics.

In 1968, when the original E.A.T. (Experiments in Art and Technology) launched, the project paired artists with engineers. But today, artists are their own engineers. The NEAT material list reads like the contents of a futuristic hardware store: custom software, thermal plastic, 3D printed housings, and LEDs galore.

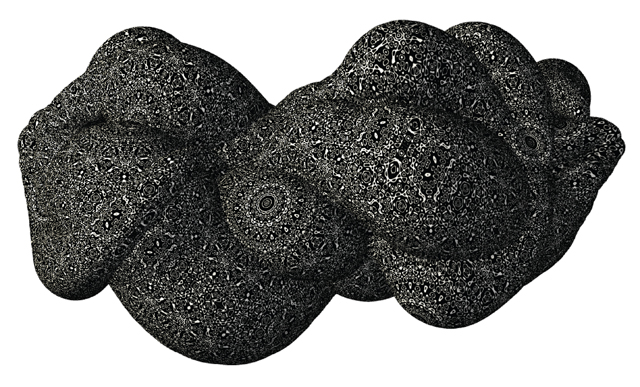

What do experiments in art and technology look like today? Many are kinetic. Many produce light. Many invite participation. In the CJM’s darkened upstairs galleries, the ambiance is that of a less-rambunctious, more meditative Exploratorium. Balancing visible machinery with mysterious inner-workings, the works in NEAT routinely provoke a sense of wonder, if not outright play.

The very first work to greet visitors is Paolo Salvagione’s Rope Fountain, a group of six gently oscillating ropes circulating through motors mounted at the baseboards. The ropes move in tandem like synchronized swimmers, whirring and slapping at the gallery floor. The temptation to touch them is almost unbearable.

Thankfully, Scott Snibbe’s interactive pieces quickly fulfill that desire. The experiences he provides are both public and private — visitors don headphones to hear music and touch iPads running custom software, others witness graphic renderings of their actions projected large-scale on the gallery walls. The most thrilling of these synesthetic stations is REWORK_ (Glass Machine); with the ease of just a few touches, museumgoers can produce their own Philip Glass-esque tunes.

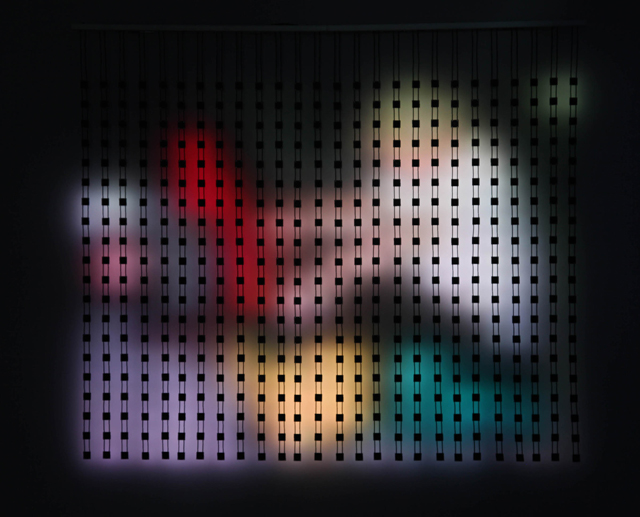

Nearby, Camille Utterback’s Entangled invites a more full-body interaction with the art. As visitors step into the light of two projected rectangles, their figures translate into fragmented patterns on a two-sided scrim. The work creates a strange vertiginous feeling, eliciting plenty of dreamy arm-waving and disoriented side-stepping as visitors work to decode the movement of color and shape before them.