In 1989, Josh Rosenthal was the music director of a college radio station in Albany, NY, determined to lure Elvis Costello onto his show. But Rosenthal’s contact at Costello’s label, Warner Bros., stonewalled him. Unfazed, Rosenthal went direct, entreating the songwriter with a note and a cache of cassettes delivered to his hotel. Costello personally accepted. Rosenthal sent a limo. The Warner rep, impressed by Rosenthal’s audacity, planted him in a publicity position at Columbia Records straight out of college, effectively poaching the young record man from A&M Records — where he had another job offer.

It’s a pivotal scene from Rosenthal’s first book, The Record Store of the Mind, a collection of memoir and reportage that meditates on both major-label machinery and marginal, unsung artists alike. Rosenthal ate latkes with Lou Reed and garnered gold records for his part in reviving bluesmen and breaking rappers in the same fiscal quarter. And yet, those gold plaques live in the closet; The Record Store of the Mind privileges the quiet euphoria of listening. It tells the stories of artists such as Dino Valente and Smoke Dawson, figures largely forgotten until Rosenthal lent his ear and a belated platform with Tompkins Square, the Grammy-award winning label he founded in 2005 after a decade at Sony.

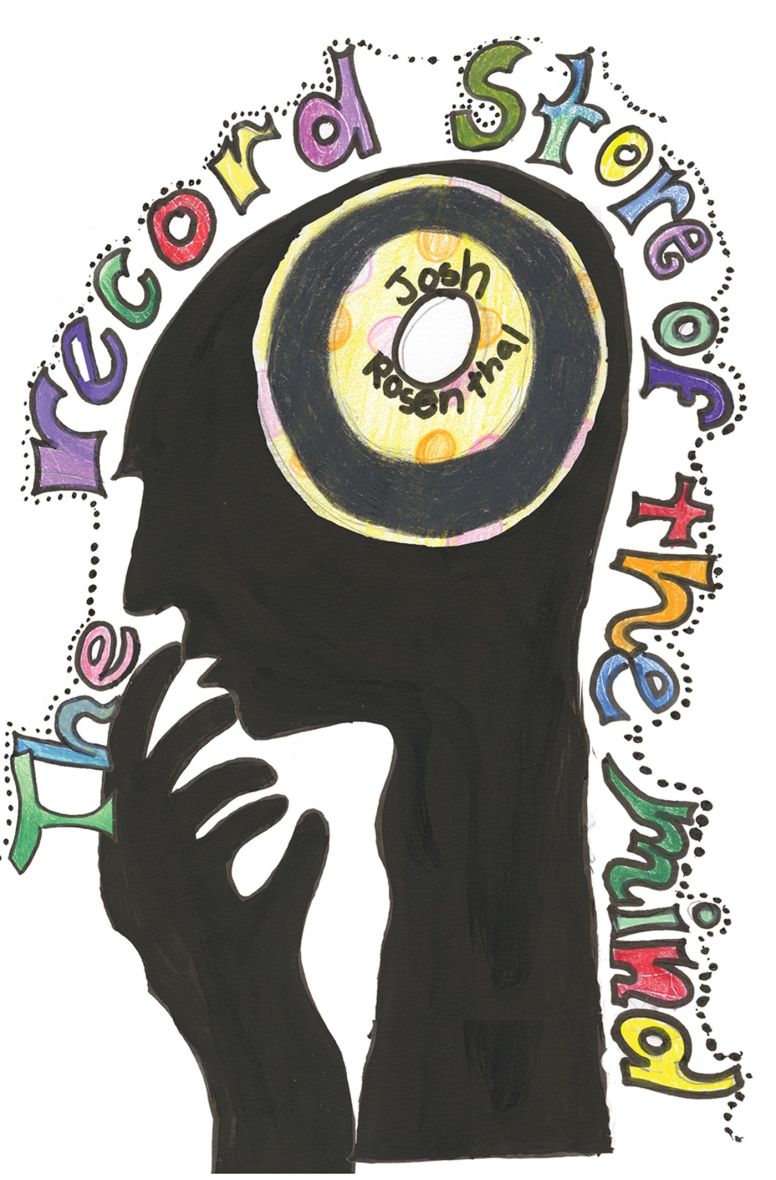

Self-published, Rosenthal’s book physically evokes the homespun records he writes about. The title — spilt across the cover in crayola-psych lettering — is clunky in a way that signals deeply personal exhibition and charming ambivalence towards commercial conventions. And for a book that considers the trend of quasi-communard folkies appearing on album covers with their babies, the cover imagery’s origin is rather apt.

“My younger daughter said she drew me a book cover for my birthday present,” Rosenthal says, seated beside the Presidio Officers Club fireplace on a recent afternoon. “I had an idea already, so I said, ‘Oh, that’s nice,’ but then she showed it me and I went ‘You win, that’s the cover.’”

And in the introduction — a Bay Area record store flyover and a paean to physical media — it’s his daughter who poses the book’s central question. Impatient with her dad, surely, she wonders aloud, “How do you know what you’re looking for?”

Rosenthal, 48, grew up in Syosset, Long Island — the origin of Lou Reed and Billy Joel, to the pride of the author and his peers, and where he first discovered the profound power of stray pop hits on the radio. “1970s soft-rock songs — mushy, overwrought — helped me locate my heart,” he writes, countering notions of pop as shallow or plastic with an argument that young people glimpse real, “romantic love” through the pathos of a snappy chorus and the majesty of melody. Rosenthal says that his close childhood friend, the filmmaker Judd Apatow, drew upon their shared upbringing for his cult TV series Freaks & Geeks, celebrated for its unusually keen sensitivity to the pangs of adolescence.