Coming up as a young feminist punk, I regularly attended events merging art, performance, music, speakers, politics, and nourishing food. Rag-tag and DIY, these happenings allowed my community to tell our own stories, and provided a space to explore trangressive ideas of gender, place, class, and society. They also usually took place at unexpected venues — like anonymous storefronts, guerrilla cafes, and private houses.

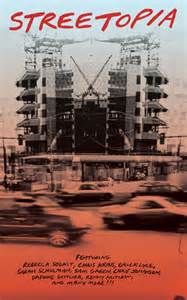

Streetopia, a new book bringing together art, photos, essays, interviews and speeches from a 2012 “Anti-Gentrification Art Fair” in San Francisco, is a reminder of why such guerrilla spaces and actions remain crucial.

Edited by Erick Lyle, Streetopia acts in part as a historical archive of the festival — curated by Lyle, Chris Johanson and Kal Spelletich — which spanned five weeks and 43 free live events in venues across San Francisco. Participating artists included Barry McGee, Monica Canileo, Swoon, and Emory Douglas. Visual art and sculpture were just two aspects of the ambitious, layered project, which also included a daily free food cafe (inspired by the Black Panther’s Free Breakfast for School Children program), ongoing exhibits, Tenderloin people’s walking history tours, street dance performances by artists like Brontez Purnell of the Younger Lovers, daily speaking events, DIY herbal medicine classes, and skill share workshops.

In a story that’s become all too common, Lyle moved in 2009 to Brooklyn after being evicted from his Bay Area home — a sad blow for San Francisco, which lost a long-time chronicler of its subterranean sociopolitical histories. Take the excellent “The Epicenter of Crime: The Hunt’s Donuts Story,” Lyle’s essay about the “thoroughly and irreducibly criminal” coffee shop at 20th and Mission where winos, prostitutes, gang members and graffiti writers took donut breaks side by side. His classic book On the Lower Frequencies paints a detailed history of the punks, activists, and misfits who squatted in an abandoned pool hall at 949 Market in 2001, turning it into an thriving community space, complete with a free cafe. And as the editor of Scam zine and a homeless activist, Lyle played an integral role in trying to keep radical politics and messy, sometimes desperate utopian dreams of equality and creativity alive, even as those ideals in San Francisco became swallowed by startups and tech wealth.

“Streetopia [the festival] was in some ways an attempt to continue the collectivity and non-monetary exchange of culture embodied in the 949 Market squat in more traditional venues,” writes Lyle in the new book’s introduction. These venues included the Luggage Store Gallery — the home base for Streetopia — along with the Tenderloin National Forest.

Initially conceived as a way to document utopian movements in San Francisco, Streetopia the event soon morphed into a reaction, writes Lyle, to Mayor Ed Lee’s announcement of “ambitious and contentious” plans to redevelop the Mid-Market Street area into “dot-com corridor.” At this point, Twitter entered the picture — aided by an unprecedented payroll tax break, offered as enticement for tech firms to choose long-neglected Market Street for their headquarters rather than Silicon Valley. The area was soon christened a new “arts district,” despite the fact that artists and nonprofits “scrambled to find studio and exhibition spaces in the Tenderloin and around Sixth Street in the wake of concurrent city plans to re-brand these historically low-rent areas — long slandered as the city’s skid row.”