The history of Yosemite Valley is long and storied, complete with the eradication of the grizzly bear population, adventurous entrepreneurs, violently displaced native peoples and the bizarre Bracebridge Dinner — an annual Christmas pageant staged since 1927 that transforms the picturesque Ahwahnee hotel into an old English manor filled with food, song and dance.

Less known within these colorful stories is the role visual artists have played in capturing and preserving the Yosemite Valley in the popular imagination, and ensuring its continued existence as a national park today.

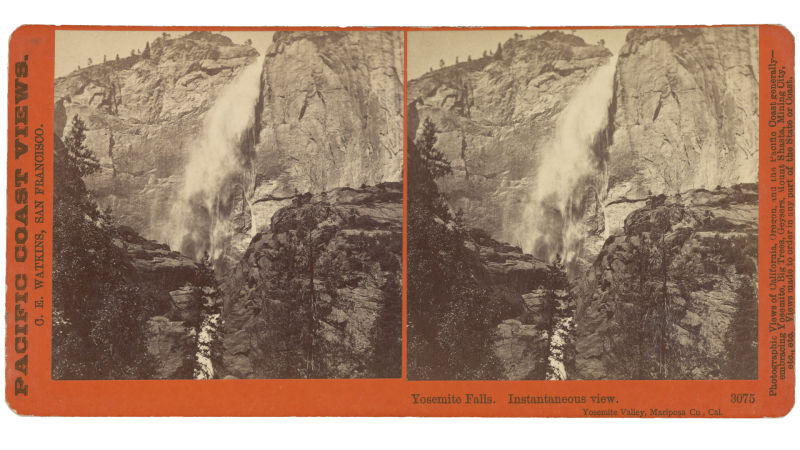

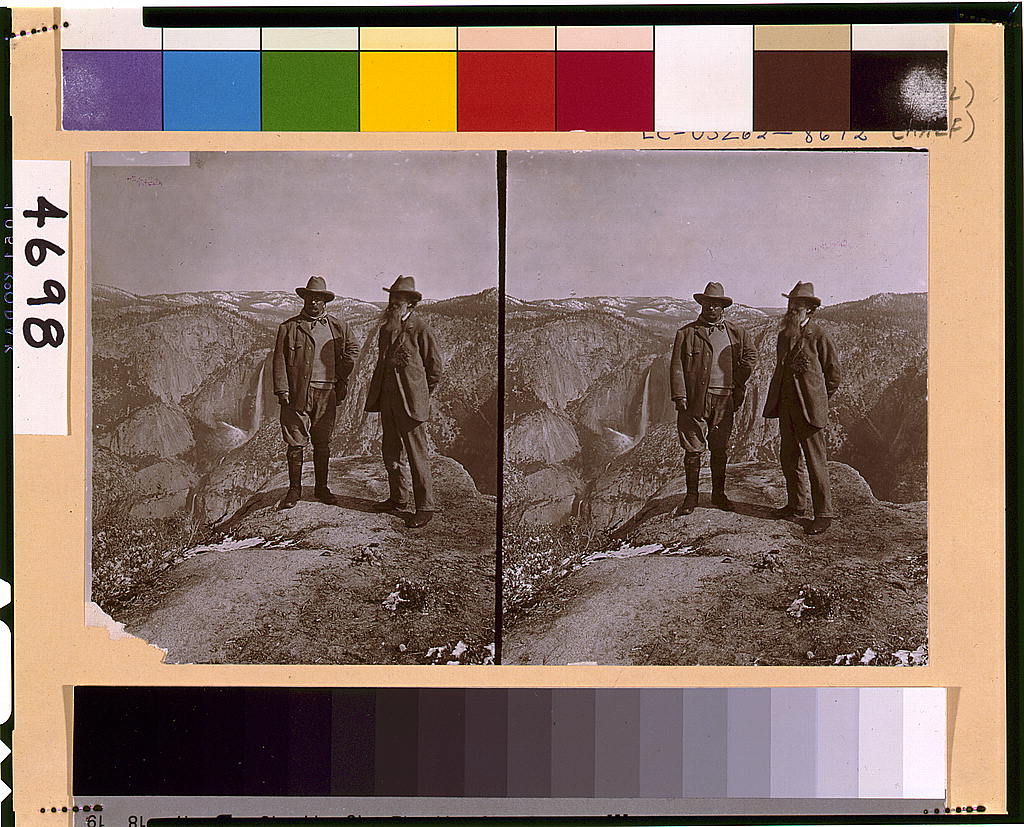

Those dramatic, romantic, impossibly beautiful landscape paintings and faded sepia-toned photographs you breeze by in a museum actually helped shape public interest, presidential opinions — and, ultimately, legislature. While influencing federal environmental policy may not have been their original intent, these artists helped to change the course of American history.

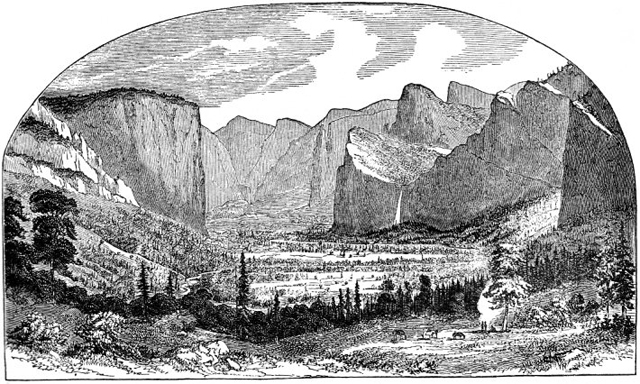

But let’s back up a bit. After Yosemite Valley’s “discovery” by the Joseph Walker Party in 1833 (Native Americans called the valley home for somewhere around 8,000 years prior), James Hutchings, a carpenter, aspiring gold miner and journalist, helped put the Valley on the map with his Hutchings’ California Magazine, published between 1856 and 1861. The first issue, a self-proclaimed “forty-eight pages of interesting reading matter, in double columns” also featured the very first illustrations of Yosemite Valley, rendered by another failed gold miner, Thomas Ayres.

Hutchings’ magazine turned Yosemite into a destination, bringing tourists and entrepreneurs of all kinds to the region. The stampede of visitors brought international fame to the landscape. But it also led to environmental degradation. While today the idea of preserving a remarkable landscape seems like second nature, back then it was wholly new. What force could possibly be strong enough to save Yosemite Valley?