If you’ve wandered through the International Terminal Main Hall Departures Lobby at SFO this month, you may have noticed SFO Museum’s newest exhibit, The Allure of Art Nouveau: 1890–1914. It focuses on a movement that inspired incredible creativity in everything from jewelry to architecture, and was inspired by nature at a time when the harsh, dehumanizing aspects of the Industrial Revolution were freaking people out.

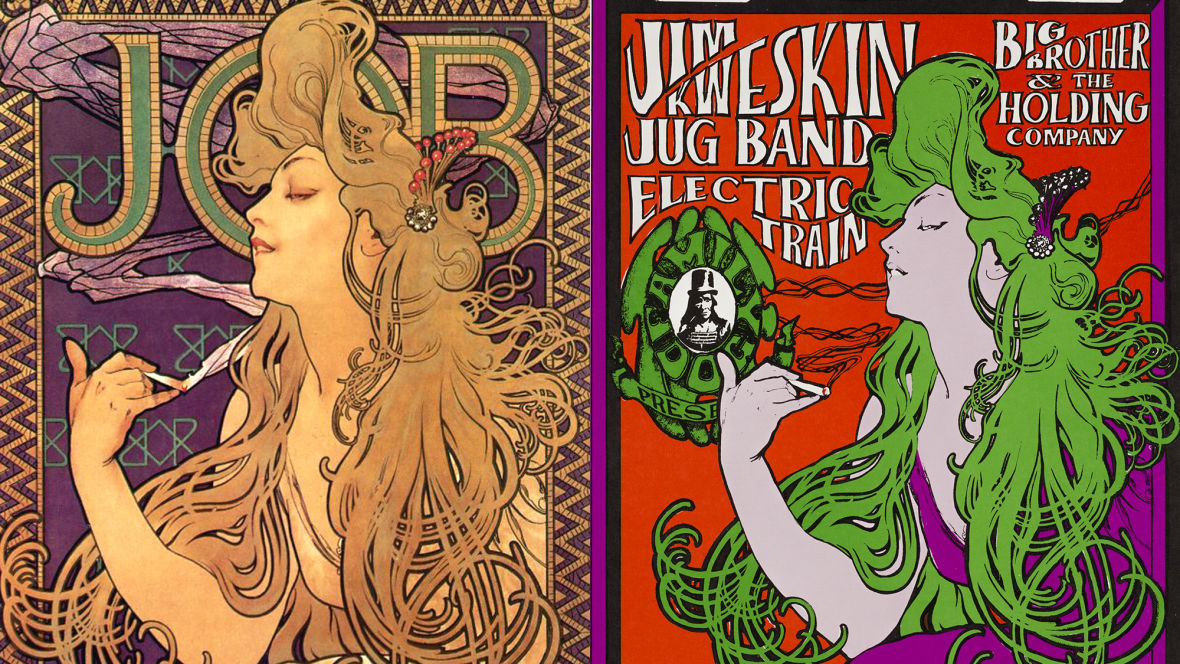

In contrast, Art Nouveau celebrated organic life: curling tendrils of vegetation, vivid colors, and lots and lots of curvaceous women. Art Nouveau slid out of fashion by World War I, but echoes of its influence have burbled up through the decades — most notably during the heyday of rock concert posters and handbills in the late 1960s and early ’70s. Some of those artists are alive and well, and still living in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Norman Orr, who did about a dozen posters for Bill Graham from 1970 to ’71, says he was influenced by was the Moravian artist Alphonse Mucha (1860-1939). “It was the sensuality of the graceful, flowing lines of the Mucha work, and the way that the female form was combined with the sensuality of the line work that I found to be most appealing.”

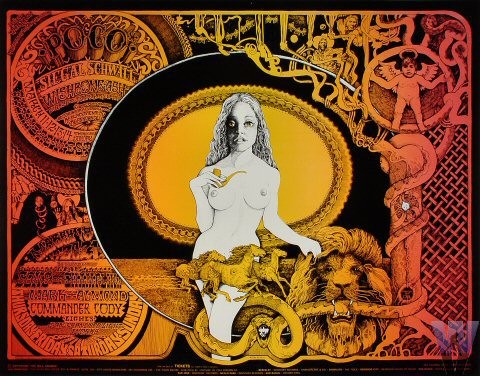

“In my poster for the Poco concert,” Orr says, “I employ a flowing quality to many of the design elements. The snake element, and stylized foliage are reflections of the admiration that I had for the Art Nouveau style.” Orr, now based in Mountain View, still works in a medium – wood – those artists would appreciate.

Jim Phillips of Santa Cruz goes even further.