This is the result, so far.

Just to be clear: this is not the sound of the actual Tsar Bell. It’s a digital simulation of what the bell might have sounded like.

Adventures in sound

Chafe and a group of like-minded scientists, musicians and artists have been playing with sound for several years now. In 2013, they riffed on climate change with a project called Polar Tide, performed at the Venice Biennale. The sound art installation involved computer simulations of bells that dropped in tone as an imaginary water level around them rose. In 2014, the team created software that allowed members of the public to dictate the sounds coming out of Hoover Tower Carillon at Stanford.

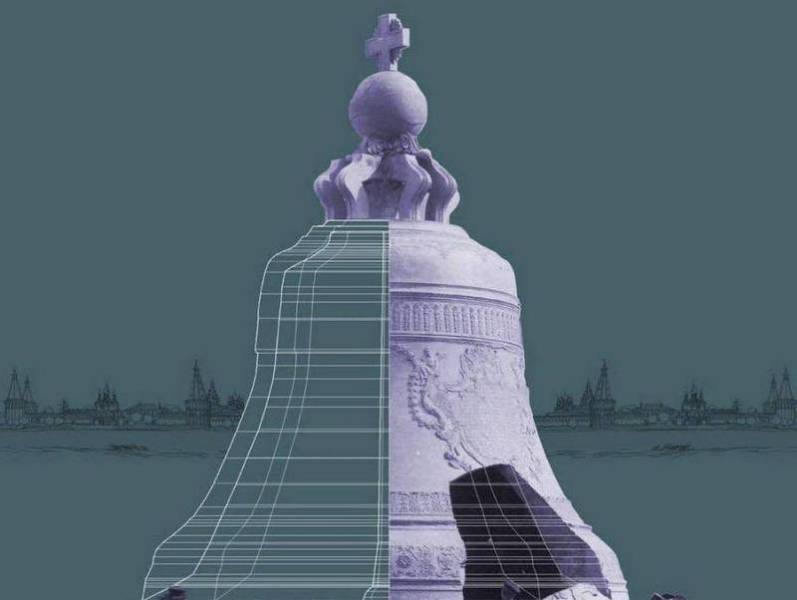

The scientists in the group began their exploration of the Tsar Bell by playing with small pieces of metal and then small bells. “We’re using techniques which come from mechanical and civil engineering,” Chafe says. “You design computer models of large things and you stress them, or you bang on them and you see how they vibrate.” Hit a bell and it vibrates in the air. These “deformations” create sound.

The “sound” is a set of partial frequencies. “So we have a list of the potential frequencies that this big, old bell would have produced had it ever been rung intact,” Chafe says. “We take that list and then we use a computer synthesis program to then recreate that sound that was found in the analysis, but do it in real time as a computer music instrument.”

Eventually, Chafe and his colleagues drew a model of the Tsar Bell on the computer, and subjected it to conjectural analysis. Chafe says the team got advice from an expert in bell acoustics. The expert thought the team was employing way too many partial tones in the simulation. “So we weeded those out,” Chafe says. “In fact, we went from almost 1,000 partial frequencies down to 61 in this version.”

An emotionally evocative exercise

Olya Dubatova is the only Russian-born member on the team — and an artist. “It was incredibly powerful and moving for me,” Dubatova says, noting church bells have long held great symbolic value in Russian culture.

Dubatova recalls a climatic scene in Andrei Tarkofsky’s masterpiece film Andrei Rublev. In 16th century Russia, a young boy convinces the authorities he has the know-how to cast a giant bronze bell. Once it’s completed, the moment of truth arrives. In front of a doubtful crowd, including a group of sophisticates from Renaissance Italy, the young Russian proves himself, and by extension, his country. “The sound of the bell was the most important sound before the Soviet Union,” Dubatova says. “People really want to go back to tradition and restore that legacy.”

The moment of truth for the Tsar Bell simulation

Team member Greg Niemeyer, director of the Berkeley Center for New Media, supervised the stereo system installation at Sather Tower ahead of the concerts. What kind of sound system can handle these deep, subsonic tones without distortion? A purpose-built set of 12 speakers from the Berkeley acoustics company Meyer Sound. “These are very big waves,” Niemeyer says. “These are very long waves. They need to pushed hard to sound good.”

Niemeyer expects people to be able to hear the “bell” throughout Berkeley. “We hope that it’s going to be an experience that takes people places where they don’t often go,” he says.

In addition, the team members have come up with music inspired by their interaction with the Tsar Bell. Chafe is one of the three composers. The other two are DJ Spooky and Jeff Davis, Cal’s chief bell ringer, or “carillonist.”

Chafe’s composition, June’s Ring, follows in the same vein as a piece he did for ships horns performed in the harbor of St. John’s, Newfoundland. “These are big ships, and that’s a big harbor,” Chafe says. “It’s a different piece depending on where you are in the city. If you’re close to a big ice breaker on one end of the port, and far from a little tug boat, you hear one concert, and vice versa.

What’s next for the team? The Liberty Bell? Or, if size is the driver, the scientists and artists involved in this work could look for Burma’s Dhammazedi Bell, said to be bigger than 300 tons. The 15th century monster is believed to be lying somewhere underwater in the Bago River.