After 25 centuries Sophocles’ Antigone is still the sharpest theatrical take on state power and dead bodies. King Creon’s refusal to bury his niece’s Antigone’s brothers and Antigone’s defiance of the King’s decree shows how politically and dramatically potent a corpse can be.

There have been too many corpses in San Francisco recently — the bullet-ridden bodies of Alex Nieto and Mario Woods — killed in strange and discouraging encounters with the police. The resulting outrage has produced hundreds of modern day Antigones: political activists storming City Hall calling for the resignations of Mayor Ed Lee and Chief of Police Greg Suhr; low riders shutting down Valencia Street; and, most dramatically, the 17-day hunger strike by the “Frisco Five” at the Mission Police Station which came at least to a temporary end over the weekend.

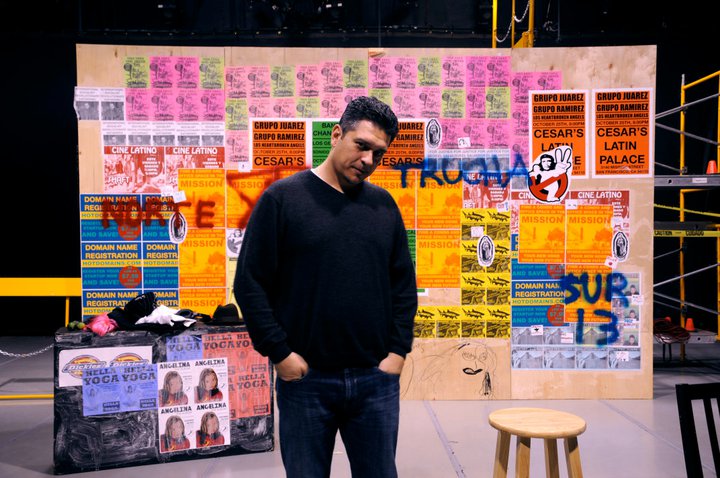

There is only one corpse in spoken word poet and novelist Paul Flores’ solo show, You’re Gonna Cry. Its understated and dismaying entrance into Flores’ portrait of Mission district in the mid-1990s is shocking, especially in the way the dead body just kind of appears and then just as quickly fades away. It’s a horrible sequence, not really related to state violence, and yet in spite of the 20-year difference in time between the events depicted in Flores’ play and today, it somehow feels of a piece with what’s happening now.

It takes a while for Flores’ play to get going. When it does, it bounces deftly between sharp political commentary, goofy fun, and a surreal sense of tragedy. It’s one of those one-man shows that seems to include everyone in the world. Of the most important, there is Cesar, a young Chicano poet; Lydia, a Latina party girl; Richard, a tech worker and new homeowner; Ronnie, a drug-dealing puppeteer; Bianca, his 7-year old niece, who feels the dangers of the world with an aching calm; and Chingon, a kind of all-seeing hipster of the street. And that’s just the beginning of the neighborhood.

There’s not much of a plot, just the desire of each character to take on the world and experience everything that the Mission had to offer at that time. For Cesar, it’s the beginning of a political bohemia; for Lydia, a chance to escape her traditional and domineering father; for Richard, the white man’s journey into a world he sees as more vibrant and alive than suburban Palo Alto.