Today, the ground floor of the building at the corner of Turk and Taylor Streets in San Francisco’s Tenderloin district is a nondescript concrete rectangle; it stands unassuming, seemingly unimportant. But as a historical marker in the sidewalk will tell you, this was once the site of Compton’s Cafeteria, a background to one of the most historic and little known events in queer history.

Three years before New York’s Stonewall riots, a drag queen at Compton’s Cafeteria, sick of the continued harassment she and her community experienced at the hands of the San Francisco police department, threw her coffee in the face of the officer who grabbed her arm. Other patrons joined the fray; the confrontation erupted into riot of thrown dishware and overturned tables, following the police out onto the street as they called for backup. Sugar shakers went through the cafeteria windows and glass doors, drag queens beat police with their heavy purses, and a corner newsstand went up in flames. As filmmaker Susan Stryker narrates in her 2005 documentary Screaming Queens, so launched the “first known instance of collective militant queer resistance to police harassment in United States history.”

Screening on KQED Saturday, July 23, Screaming Queens: The Riot at Compton’s Cafeteria has a particular resonance now, 50 years after the event that inspired its making, as the need for queer safe spaces becomes a subject of focus once again.

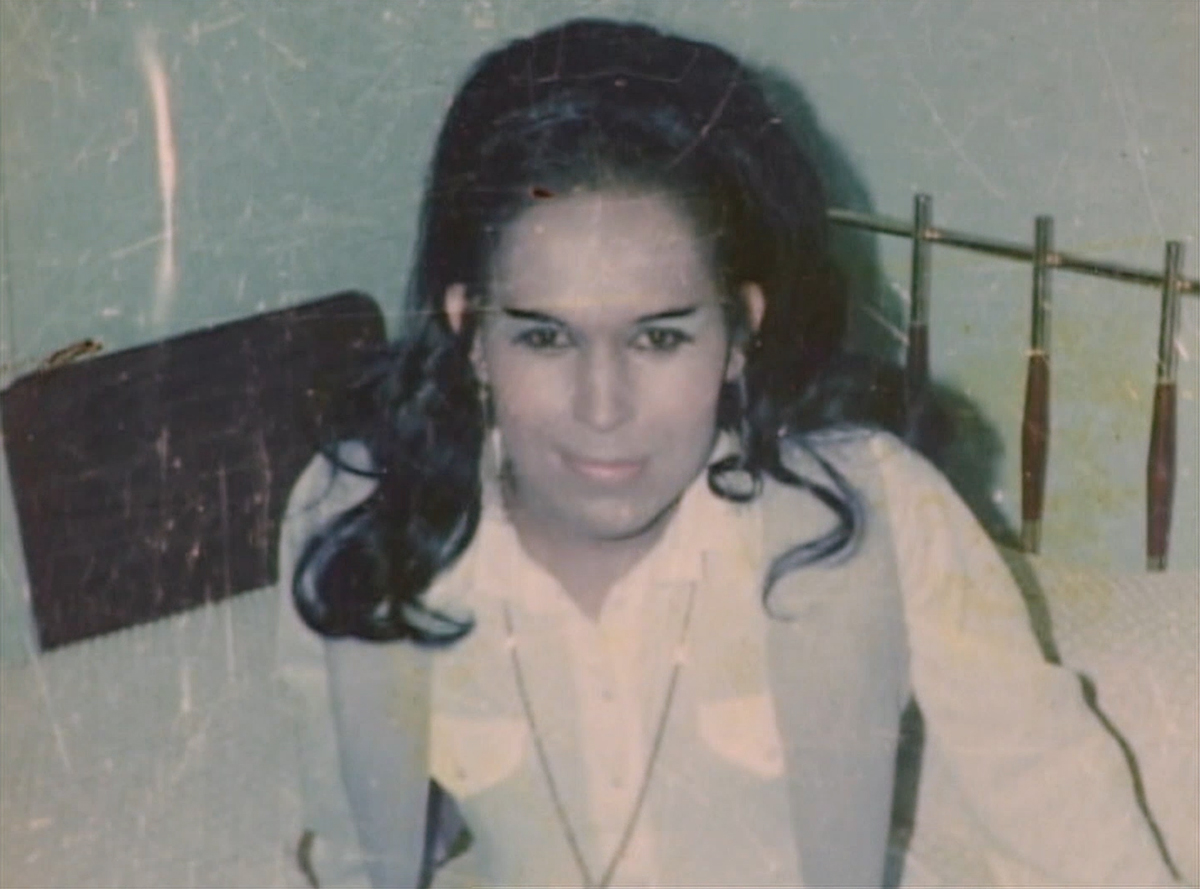

Overshadowed by Stonewall, the riot at Compton’s Cafeteria might have remained a little-known, almost mythical event that took place “one hot August night,” until Stryker dug deep into the GLBT Historical Society archives and tracked down the people who remembered the Tenderloin as it was.

“It was beautiful because it was clean,” says one of Stryker’s interviewees of Compton’s. “It was like Oz,” says another, “something like The Wizard of Oz.” The cafeteria served reasonably-priced food 24 hours a day, acting as a gathering place for drag queens, trans women, sex workers and down-and-out individuals into the wee hours of the night.