In the course of her remarkable life, Sojourner Truth (c. 1797 – 1883) sat for photographic portraits on at least 11 occasions. By itself, this fact is significant. As an illiterate former slave, Truth’s humanity and the humanity of all her fellow African Americans was barely acknowledged, let alone celebrated in an artistic form so esteemed as the portrait.

“I sell the shadow to support the substance,” it reads beneath her portrait. Truth’s sale of her photographic shadow served causes no less significant than personal and collective emancipation.

At the UC Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA), the intimate exhibition Sojourner Truth, Photography, and the Fight Against Slavery presents many of the portraits Truth commissioned. Surrounding those images are their context: the complex paper exchange that by turns “justified” the treatment of enslaved Americans and the Confederate cause, and also helped bolster political resistance to institutionalized human bondage.

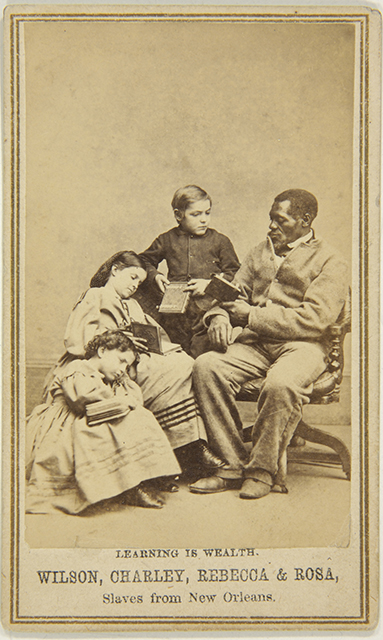

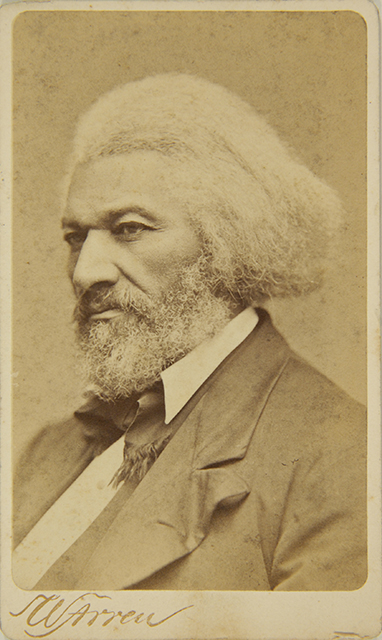

Twenty-first century image saturation traces its roots directly to photography’s dissemination in the nineteenth century. Though many photographic forms were popular at the time, the cartes de visite — small cards fitted with miniature portraits — outstripped daguerreotypes and tintypes. Cartes de visite shaped social exchanges — they were both collectible objects and an inexpensive means of establishing one’s identity.

While only privileged white Americans could afford to commission painted oil portraits, photographic portraits were easy to produce and inexpensive to purchase. Truth marshaled her prescient understanding of this emerging communication and political tool to support abolitionist and feminist efforts, and to claim herself as more than a product of abject circumstances.