Certain artists become famous not just for what they achieve, but for what the art historical consensus believes they could have achieved had they not died young. Jean-Michel Basquiat, Francesca Woodman, Keith Haring, Felix Gonzalez-Torres — none reached the age befitting a mid-career retrospective, all left us with the tantalizing beginnings of potentially monumental art practices.

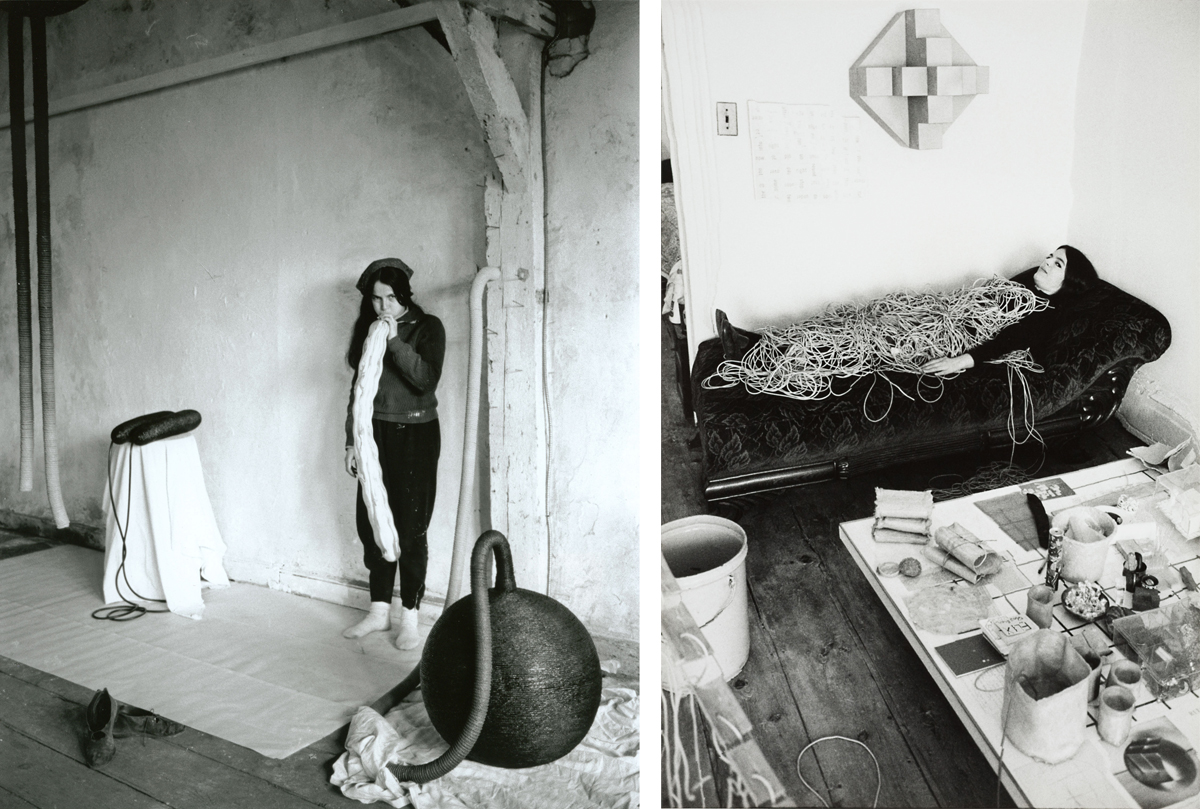

Sculptor Eva Hesse is a member of this “what might have been” club, a prodigious and adventurous maker who died in 1970 at the age of 34, just five years after bursting onto the New York art scene with her particular brand of “eccentric abstraction.”

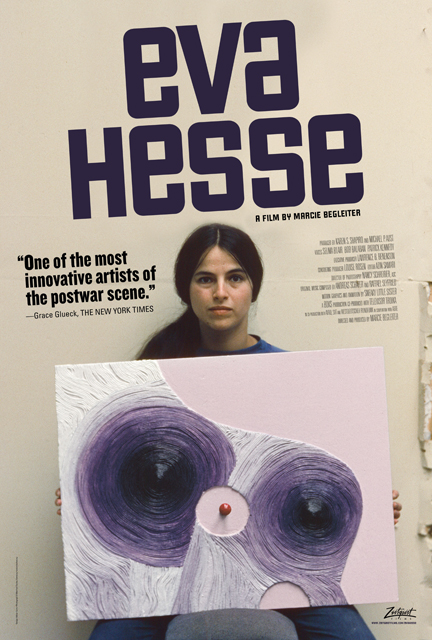

Marcie Begleiter’s new documentary on Hesse (remarkably, the first documentary about Hesse’s life and work), simply titled Eva Hesse, dwells not so much on the imagined possibilities of a lengthy career, but on Hesse’s dedication to her art. Hesse’s work is beautiful and important, yes, but Begleiter’s lens focuses on her ability to transform emotional turmoil, personal tragedy and even her own uncertainty into art that was wholly her own.

Born into a Jewish family in Hamburg, Germany in 1936, Hesse and her older sister Helen were evacuated via Kindertransport to the Netherlands in 1938, away from the Nazi regime. Reunited six months later, the Hesses immigrated to New York City in 1939. They were the only members of their extended family to escape the Holocaust. Learning this, Hesse’s mentally unstable mother took her own life when her youngest daughter was just ten years old.

In Begleiter’s retelling, Hesse’s early trauma and sense of isolation fostered within the artist a single-minded focus on her career. After studies at Pratt, Cooper Union and under Josef Albers at Yale, Hesse was determined to “make it” as a painter in New York. “I’m almost too anxious for every moment and every future moment,” she wrote in her journals. “I will paint against every rule.”