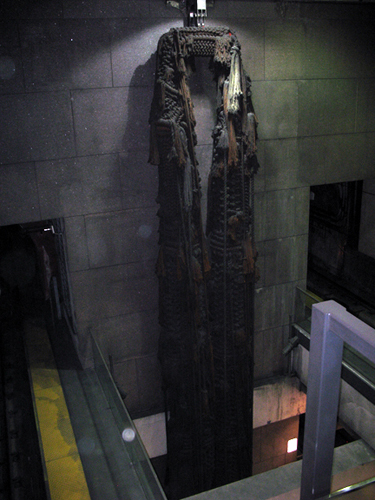

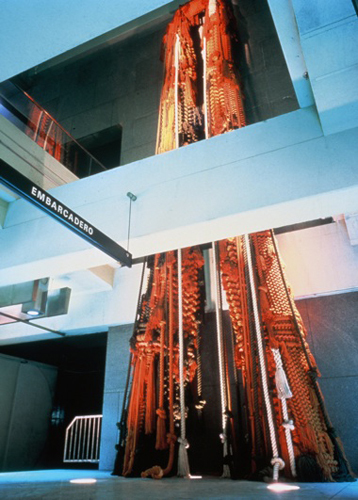

Barbara Shawcroft’s Legs (1975-1978) is a three-story-tall public sculpture, situated in the eastern end of Embarcadero BART/Muni station. It largely resembles masses of rope, but it is made from Nomex, a flame-resistant synthetic material developed by DuPont and used to create gear for firefighters. It was commissioned for permanent placement in the station at the behest of the original architects, Tallie Maule, Hertzka and Knowles Associates (Finland/U.S.), who required a budget for the installation and maintenance of two large sculptures at either end of the station as part of their design; Stephen De Staebler’s Wall Canyon (1975-1977) is situated at the opposite end of the station. Both pieces won placement after an open competition. Despite initial arrangements, Legs has only been cleaned twice in 35 years. Today it looms in the station like an abandoned monument and is strangely compelling despite its obvious neglect.

BART’s proposed 2014 Fiscal Budget suggests decommissioning the sculpture, with a potential budget of up to $300,000 dedicated to this legal and technical process. An initial public hearing was staged on May 23, 2013 to collect public input about the proposed budget as a whole; the total budget exceeds $1 billion and the proposal regarding Legs is but one line item. A second public hearing is scheduled for June 13, 2013; the board will vote on the budget that evening.

Though the cost of cleaning the sculpture is substantially less than the cost of decommissioning it, the proposed budget presents removal as the only option. The impetus for decommissioning the sculpture is unclear. Why change anything now, after so many decades? Text from the budget proposal addresses the difficulty of maintaining the sculpture, while also acknowledging that limited efforts have been made to clean it over the years. Few would argue today that its placement makes sense: airborne soot is an issue in any train station — but it was designed and placed with this concern in mind. In conversation, Luna Salaver, a BART spokesperson, suggests that larger capacity concerns should be taken into consideration, but this is not stipulated in the proposal, nor is there any assertion of hazard.

On the surface, the debate about decommissioning the work seems to be rooted in aesthetic subjectivities, at a time when permanent public art is a receding cultural value. The public hearing on May 23 was filled with more than a hundred union employees waiting to address labor issues. It is easy to see how a sculpture becomes superfluous in the short term, but public works find value in longevity. Even the artworks that fall out of vogue — or never found it to begin with — are considered visual culture in the longer view of history.

The issues at stake in decommissioning public art are complex, beyond the fact that the funds could benefit a substantial number of other creative initiatives. The proposed decommissioning also raises larger questions about the sustainability and permanence of public art in an evolving cityscape. When Legs was commissioned, the station was brand new — today it services 11,000 passengers per hour during peak commute times. Increasingly public art is moving towards temporary gestures, often privately funded, to circumnavigate divided public opinion, bureaucracy, and dwindling arts funding — the recently launched Bay Lights is a prime example.