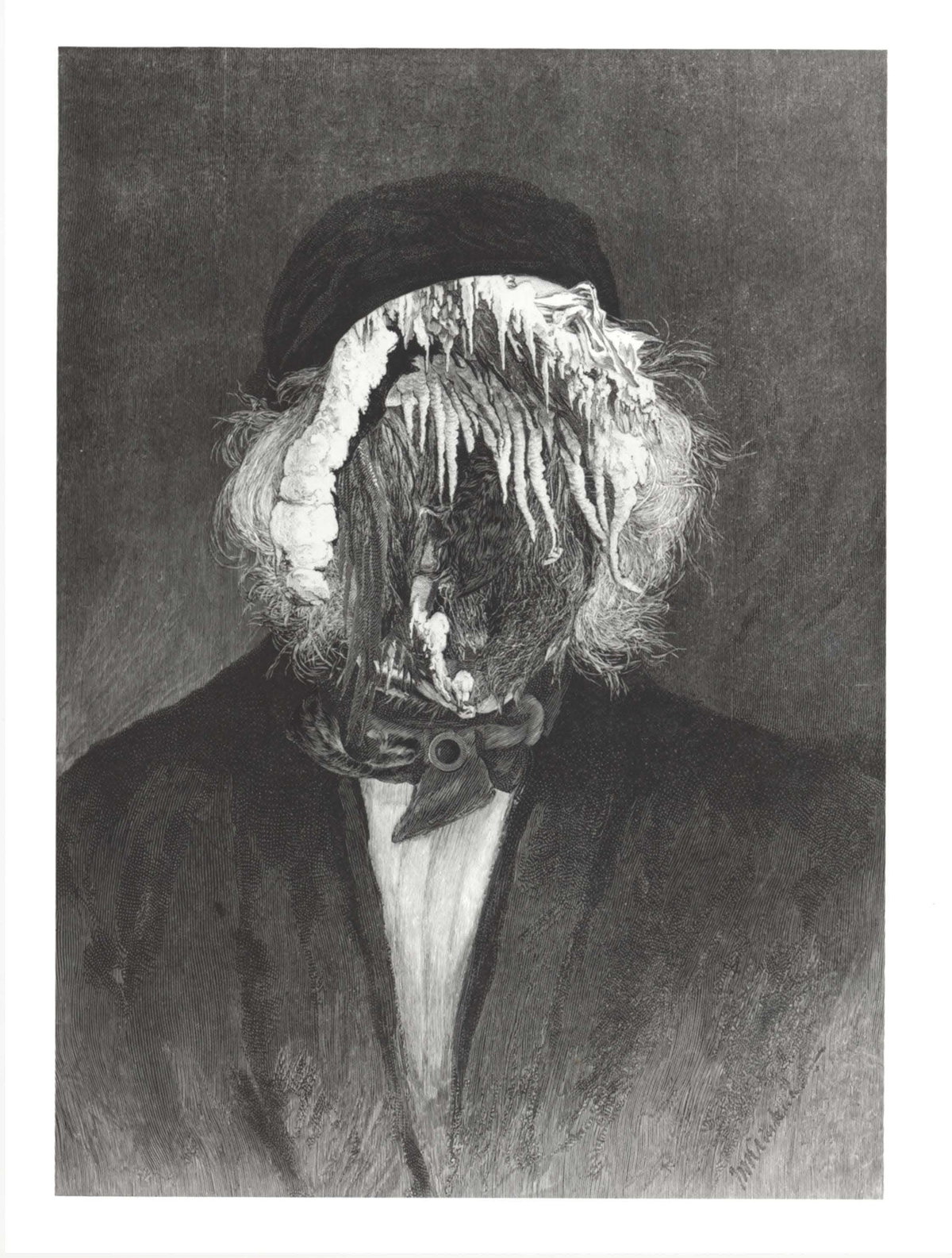

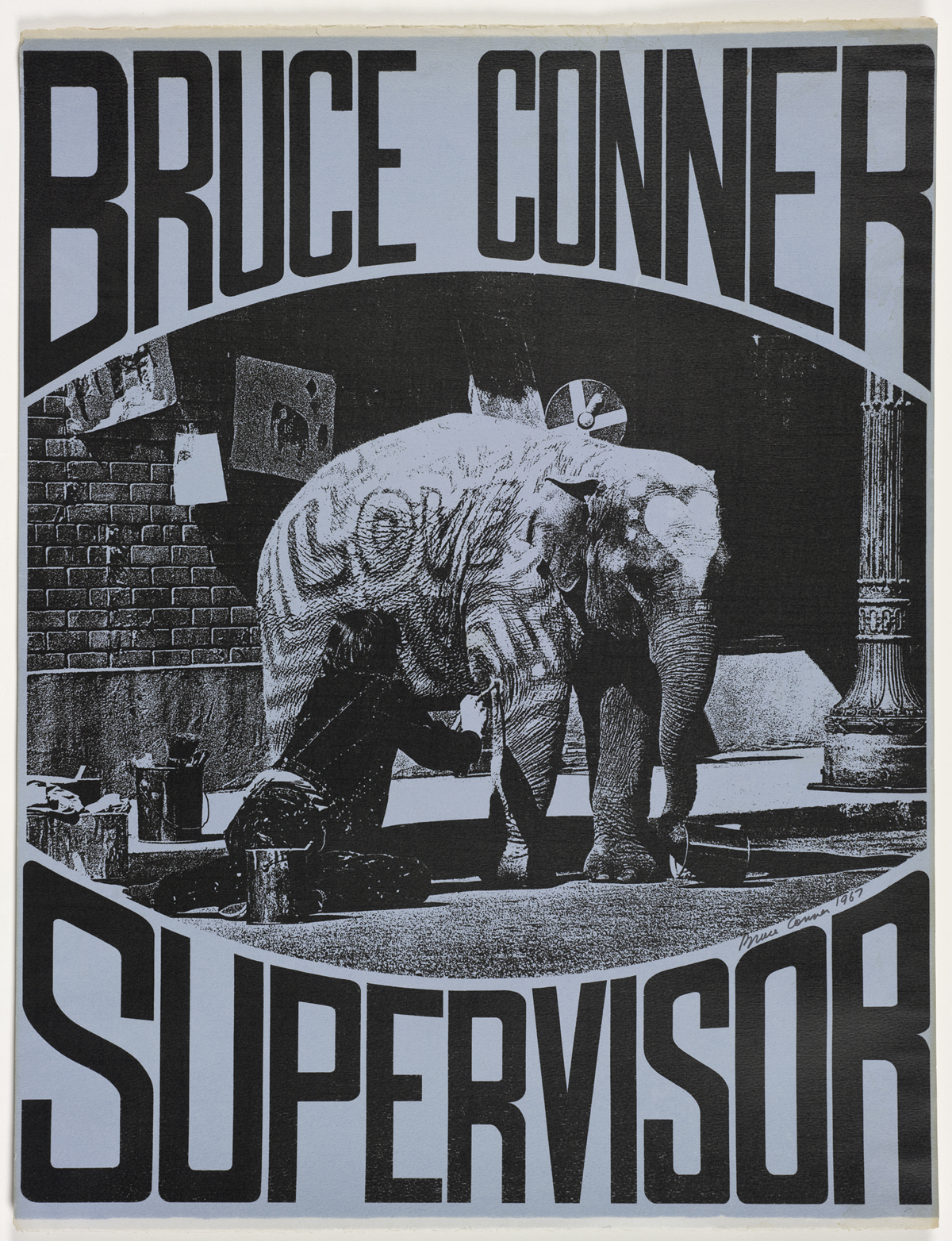

Ask any art school student “Who is Bruce Conner?” and depending on their major, they’ll provide you with a vastly different answer: a) Bay Area conceptual artist; b) experimental filmmaker; c) that guy with all the inkblot drawings; or d) “Who?”

The correct answer is e) All of the above. And more.

Conner’s prolific career, spanning the mid-1950s to his death in 2008, is now on view in SFMOMA’s mammoth retrospective It’s All True, opening Oct. 29. Over six decades, he worked in nearly every media available to artists of his generation, purposely defying both market forces and easy categorization. As soon as he gained recognition for a certain style (as was the case with his early assemblages), he had a tendency to abandon that style completely. He even “ended” his own art career by declaring himself dead on two separate occasions.

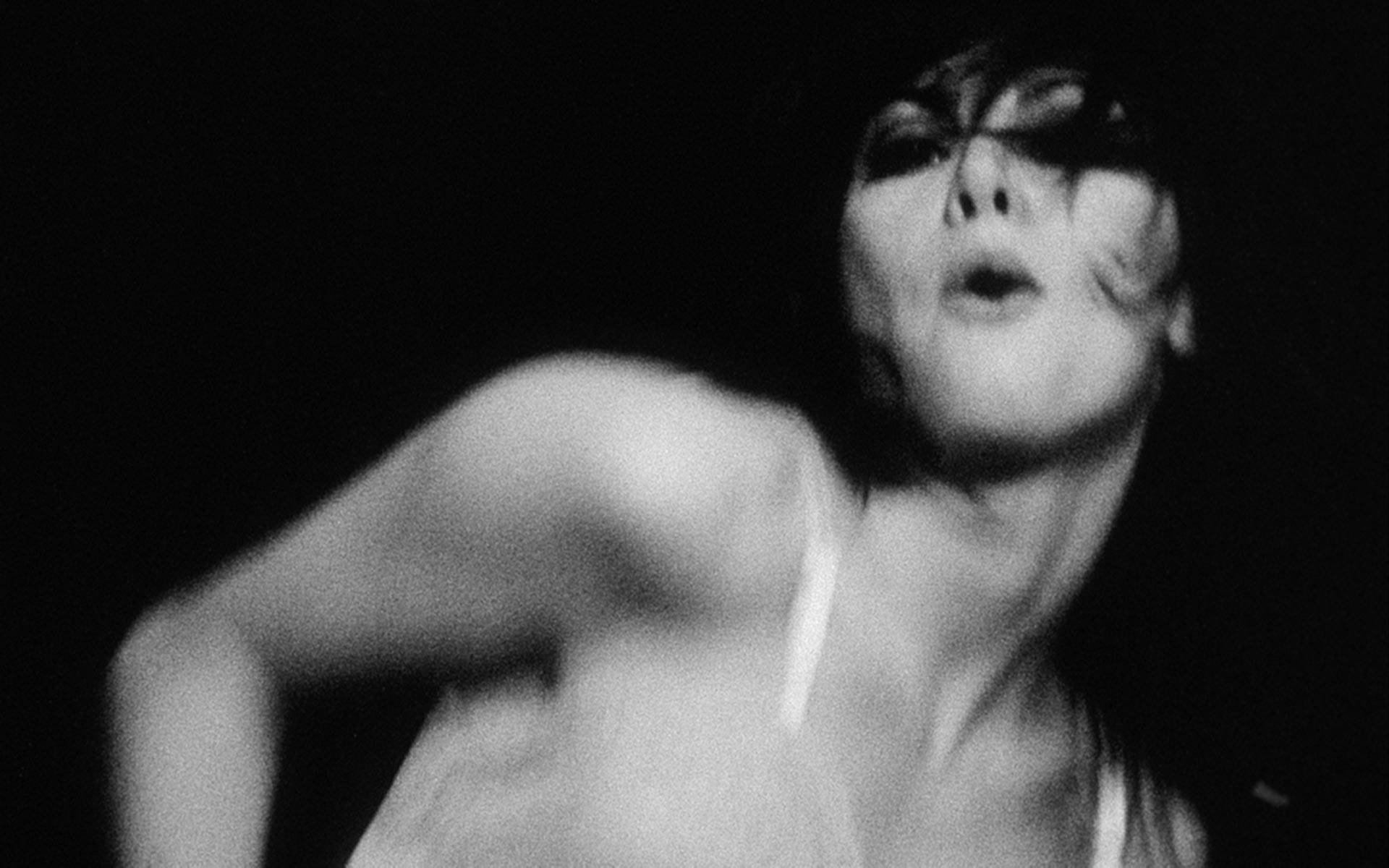

It’s All True often organizes Conner’s wide-ranging practice by material and subject matter (compare his otherworldly “angels” photograms with his black-and-white photos of San Francisco’s late ’70s punk scene), but it’s important to realize many of the works — collages, films and drawings — were made concurrently.

Nowhere is this more obvious than in the “Hecho in Mexico, 1961–62” gallery (look for the joyful light yellow walls), a room filled with works made while Conner and his wife Jean lived in the Juárez neighborhood of Mexico City. Sourcing everyday materials from his home, he covered items like shoes, a folding screen and a pillow with collaged paper, photographs and brightly colored paint. Projected in the center of these objects are two versions of the film Looking for Mushrooms, compilations of fuzzy colors, slow-motion fireworks and religious festival footage set to the Beatles’ “Tomorrow Never Knows” and Terry Riley’s “Poppy Nogood and the Phantom Band,” respectively.