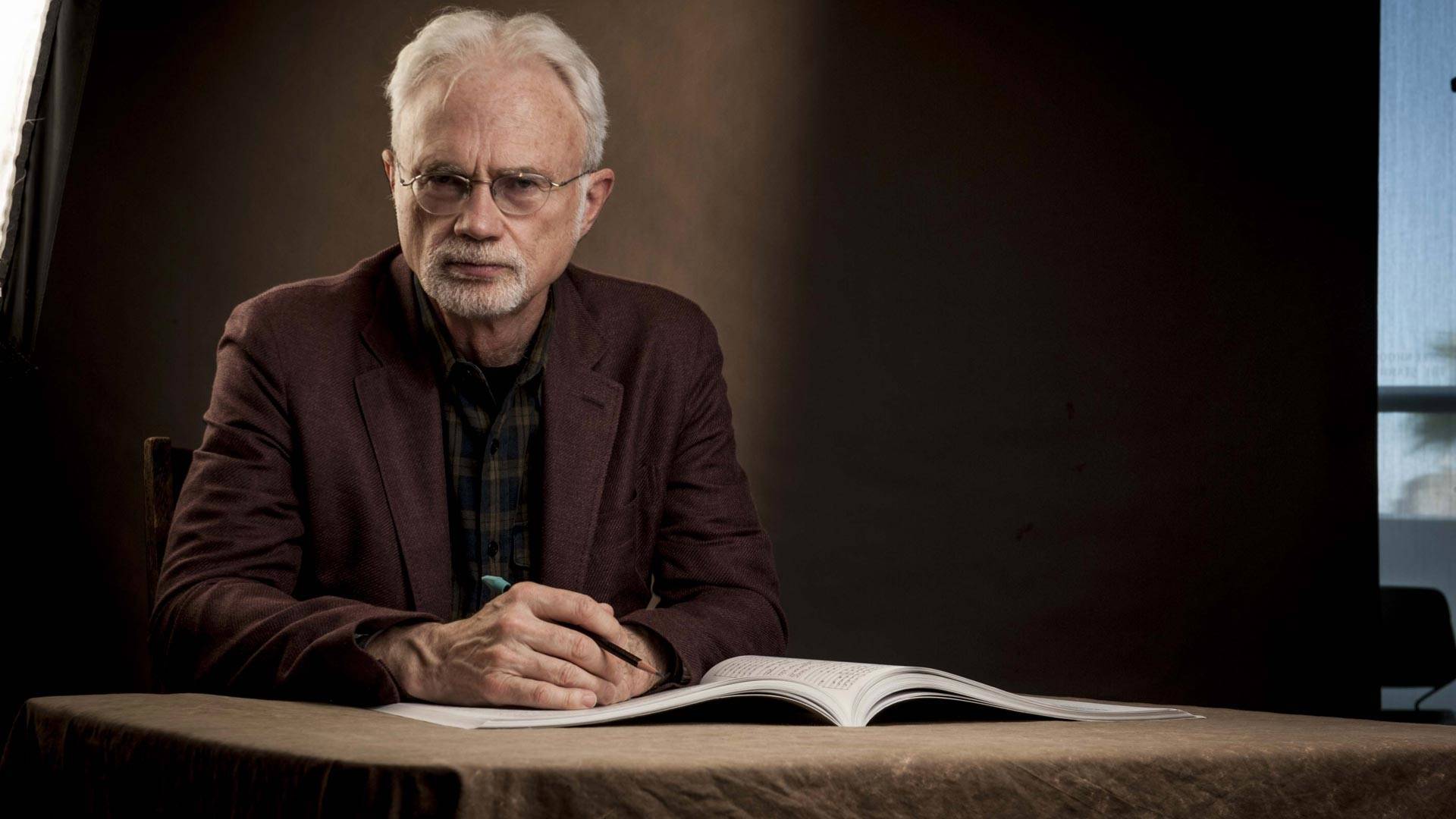

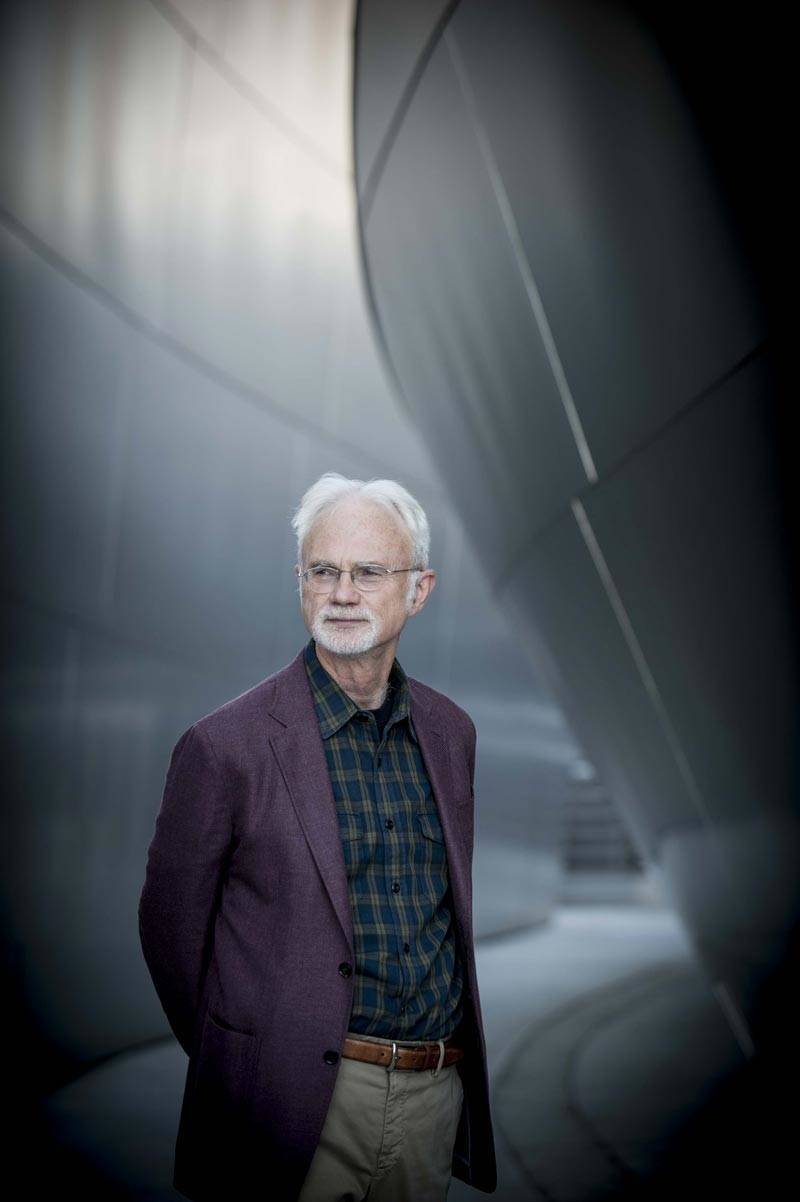

Classical music isn’t the first place one expects to find political and social activism. But then, not many classical composers are John Adams, whose stature as one of the world’s most important and respected modern composers often overshadows the fact that he listened to Jimi Hendrix and Bob Dylan in his Harvard days, resisted Vietnam, and eventually moved to what he semi-jokingly calls the “liberal bubble” of Berkeley.

Celebrating his 70th birthday this month, Adams could easily rest on his laurels — his past works have already addressed nuclear war (Dr. Atomic), feminism (The Gospel According to the Other Mary), the Middle East (The Death of Klinghoffer), and U.S.-foreign relations (Nixon in China). Instead, he’s premiering a new opera this year, Girls of the Golden West, that touches on race relations, the silencing of dissent, women’s rights, and what we now call “fake news.”

In the midst of large-scale celebrations of Adams’ work around the world (including three ambitious programs of his work at the San Francisco Symphony in February), I spoke with the composer over the phone from his studio in northern Sonoma County about life under Trump, the dangers of the internet, the efficacy of musical protest and more.

Note: Interview has been edited for length and clarity.

So, how have you been feeling these past few weeks since Jan. 20?

I think I feel pretty much like everyone I know. It’s interesting — I left San Francisco on Inauguration Day to go to Berlin, where they did performances of my big oratorio, The Gospel According to the Other Mary. It was just a cultural shock of the highest order to arrive in this city, which has seen so much tragedy and destruction because of its arrogance way back in the early part of the twentieth century — and is now the most tolerant, most welcoming multicultural city, probably in the world. To arrive as an American knowing that our country is heading full-throttle into what could be the worst social and political crisis in decades, if not in the history of the country, was a deeply shocking and troubling experience.

Did the election of Donald Trump surprise you?

Of course. I think it surprised everybody. Probably even him. I was reading the New York Times and the Washington Post, and we were all being constantly assured that it was a slam dunk for Hilary Clinton. I wasn’t the only one. It was the greatest shock I felt as a citizen since Sept. 11.

You have composed many pieces that would… I don’t necessarily want to call them prophetic, but touch on issues that are very electrified right now.

You mean like The Death of Klinghoffer.

Right, and we’ve just seen Trump’s Muslim ban enacted. There’s Dr. Atomic, and now Trump says we should build up our nuclear arsenal. Or how Nixon in China parallels with today, in a way, as a study of a leader’s personality and behavior. If you could compose an opera based on the White House right now, what issues would it comment on?

The idea of a Trump opera doesn’t interest me in the least. First of all, because so much of what he does is theater to begin with. It’s a terrible form of exploitive theater, but there’s no point in trying to make theater about theater. Furthermore, you don’t want to spend time as an artist giving your very best to a person who is a sociopath. He’s not an interesting character, because he has no capacity for empathy. The only empathy that he can extend is to his family, who are just extensions of his own ego, and beyond that, he doesn’t care. Everyone else is someone to be manipulated and controlled.

The thing with Nixon was he was interesting because he was vulnerable. His weaknesses were marvelously mixed up with his idealism. At the moment in Nixon in China where he comes off the plane, and he greets Zhou Enlai, he sings this aria about being aware of himself as president, and being like the Apollo astronaut. He’s the pilot who’s piloting the ship through shoals. You can believe that there’s a part of Nixon that is actually noble despite all his paranoia and his faults.

I couldn’t imagine doing that with Trump, because there’s just nothing there except this raw, very dangerous ego, and overwhelming vanity. Maybe if I live that long, I will find some story that reflects this crisis, but I would have to approach it from an oblique angle.

Many artists that we’ve talked to have a form of writer’s block. They’re paralyzed by this. Are you?

No, not at all. I’m just finishing an opera for San Francisco Opera, which will premiere in November, Girls of the Golden West. This opera, which I was working on all during the campaign, is based on the real, true facts of that era, and I discovered some interesting parallels. First of all, the people that came to California during the gold rush had been fed “fake news” by the media. All the journals and newspapers in the Midwest and the East even as far away as Europe were full of these bogus stories where all you had to do was get out here, and you could just bend over and pick up nuggets of gold and become immediately rich.

Which turned out to be, say, “alternative facts”?

That’s exactly it. When they got here, some people did get wealthy. But most of the people that got wealthy were the people who were smart, and didn’t make money from gold, but from supporting the influx — like people who sold food at outrageous prices. It’s amazing what the inflation of prices was in San Francisco and throughout Northern California during the gold rush.

But secondly, once things started getting tough, the white people turned around and virulently attacked the Mexicans, the Chinese, the Chileans and anyone who looked different. Of course, I’m composing this opera during the Trump campaign and feeling — what do the French say, rien de nouveau sous le soleil — there’s nothing new under the sun.

And also, my opera deals with a few very brave and feisty women who were out here, and some of the misogyny. The culminating event in this opera is an incident that took place in the tiny gold rush town of Downieville, which is just down the road from where I’ve had a cabin for the last 35 years. A young Mexican woman about 25 was being harassed by a drunken white gold miner, and she stabbed him and killed him. The whole town insisted on giving her an immediate trial, and then they hanged her from the bridge over the Yuba River.

To keep drawing comparisons to the modern day, we’ve seen so much violent behavior in the past year. Some of it encouraged, even.

It’s awful. I was composing this crowd scene where I had to make up slogans for the crowd to scream. I had to contain myself from adding “Lock Her Up.” I thought that would be just a little too close to home. Anyway, I don’t want to make it sound like I’ve written this vicious propaganda work. Actually, there’s a great deal of warmth and humor and humanity in the piece.

We just saw a massive number of women marching around the country, and with the San Francisco Symphony, you’re doing Scheherazade.2 and The Gospel According to the Other Mary, both stories with strong female characters like the Girls of the Golden West. Where do you think your empathy for women comes from?

I’ve lived with some wonderful and very strong and independent women, including my wife Deborah O’Grady, the photographer, and our daughter Emily, who is a painter. I think over the years I’ve become more sensitized to male assumptions, or presumptions. I’ve been able to look back on my own assumptions and realize that some of my own behavior, like almost every other man I know, needed a little adjustment.

But as a composer, what Carl Jung described as the female anima is such a strong force, and it really is the lyrical and expressive element in music. I don’t want to get into corny descriptions like they used to, where they said the first theme in a symphony was “masculine,” and the second theme was “feminine” — that’s a kind of embarrassing, sexist thing. But I do think of the feminine as an archetypal notion of warmth, expressiveness, understanding, and also of power. Those are the kinds of energies that are really behind the meaning of music.

What do you think about the idea that artists have a responsibility now to react to our new administration?

I think that’s an easy thing to say. I would simply say, forget the “artist” part of that and just say we all have a responsibility. Every citizen does. And how we do it is up to each individual, whether you want to get on a plane and go protest in front of the White House or whether you want to work actively in your own neighborhood to get out the vote. Everybody has to do it in his or her own way.

Your way has meant that you’ve had people like Rudy Giuliani and Ruth Bader Ginsburg comment on your work.

I got five minutes of scolding from Rush Limbaugh! I want to put that in my biography as a mark of distinction.

After that, after The Death of Klinghoffer, did you feel a need, or an allure, to create art to spur listeners into challenging ideas?

No. I don’t think that there was anything positive about that event. Some people said, “Isn’t it great that a piece of classical music caused all that controversy, and you’ve got editorials in the New York Times?” I didn’t take any pleasure from that at all, because it was deeply disturbing to be the target of an organized, online shaming campaign. The only positive thing about it was the mood inside the Metropolitan Opera. That the people who were there were very emotionally committed to it, and the fact that as the run went on, it became the best-selling opera of their year, or one of the top two or three. There was a nice satisfaction about that. But ultimately, it was a really awful experience in the fact that the Anti-Defamation League forced the Met to cancel the international telecast. It was a disgrace.

Some people today might spin that to their advantage. But you don’t revel in a reaction like that — you’re not an internet troll.

The internet is… I don’t use Facebook. My publisher has a page for me, and I do follow a very, very few people on Twitter, but they’re mostly young political reporters. I really like the site Vox.com.

The thing that I noticed about the feeds I’m reading — I was just saying this to my wife, this morning — it all agrees with my thought, and that’s the danger of the internet. People just read stuff from people that they agree with. I read all the news that kind of fits my political point of view, and I realize that people on the other side are doing the same thing, reading stuff that originates with Breitbart or whatever.

I know that we’ve had terrible crises in the country. In the past, Lincoln had to deal with these horrible anti-draft riots and terrible situations during the war, and of course we had the McCarthy era, on and on. But there’s something new and unknown that we’re really not prepared for in the country, and that’s the behavior patterns that the internet is causing. That’s one of the reasons that things are so violently divided in the country.

Everybody’s walking around right now saying, “What can we do?” Where do you see hope at this moment in America?

When I came back from Berlin on Saturday night, I came out of the customs area where they check your passport, and I heard this cheering, just a huge crowd, and then I walked into it, and there were hundreds and hundreds of people in the foyer with signs and placards. I got this rush, and it really brought me back to my student days during the Vietnam War. For years, I’ve been saying, “What’s happened to the outrage? What’s happened to the activism we showed back in the late ’60s and early ’70s?” And now I think that the country is experiencing that. It’s like a spasm.

I just read that new biography of Patty Hearst. And, you know, with the SLA, and the Weathermen, there was a lot of domestic violence during the early ’70s. I fear that that’s going to happen again, but I do think this sense of protest and outrage and activism has been aroused. It’s anybody’s call. The scary thing is that the other side has guns. Of the thousands of people that I know personally, I think I know maybe one or two people who actually keep a gun in their home. The other side has them. That’s a very, kind of unsettling and alarming thought that if we ended up actually having a social situation that borders on a civil war.