The home video revolution of the 1980s, sparked by the introduction of affordable VCRs, was a major blow to repertory cinemas. Why pay to see a beat-up print of The 400 Blows or North by Northwest with ill-mannered people in a theater when you could rent the VHS and curl up on the couch with your partner, some Jiffy Pop, and a glass of cabernet? (In reality, more people checked out the latest Julia Roberts or Richard Gere flick than Truffaut or Hitchcock. But I digress.)

The VCR killed countless rep houses, while others survived and thrived via a mix of niche first-run films, revivals of classics in new prints and carefully curated and promoted series (noir, pre-Code, Hong Kong action). In San Francisco, one of the partners at the Roxie Theater, Bill Banning, arrived at the inspired yet risky idea of snagging new films that the major distributors passed by — edgy indie narratives and documentaries about cult artists, notably — and distributing them to independent cinemas around the country.

Roxie Releasing, as the distribution wing was christened, had several advantages — the Roxie itself; San Francisco’s then-famously adventurous moviegoers (we’re talking about the ’80s and ’90s, remember); and a coterie of local critics and outlets interested in covering offbeat, out-of-nowhere movies. RR skipped the usual strategy of opening a movie in New York and parlaying reviews and ticket sales into bookings across the country. Instead, the film would premiere at the Roxie and play, and play, and play. The box-office receipts of RR titles were essential to sustaining the theater for several years while it found its footing in an evolving moviegoing environment, and movies like Red Rock West and Man Bites Dog weren’t just hits; they were phenomena that other indie theaters were eager to duplicate.

The Roxie revisits those freewheeling days on Saturday, March 4, with a quadruple feature billed as Bill Banning’s Roxie Releasing: A Tribute.

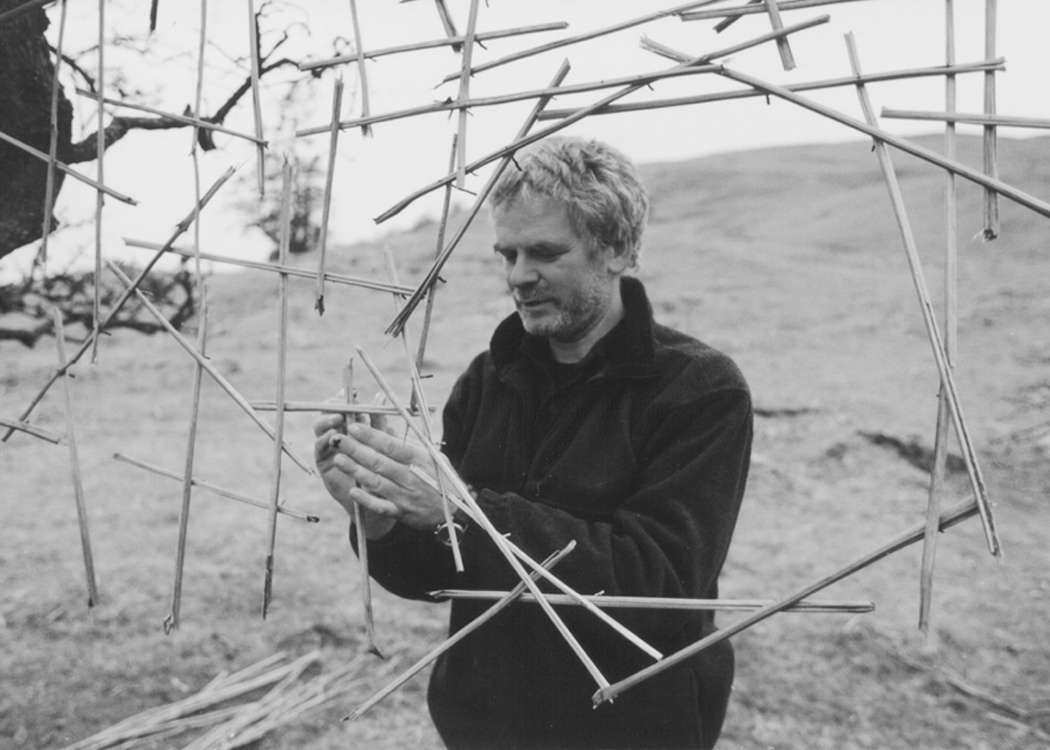

First up is Paul Cox’s gorgeous and moving Vincent (1987), featuring Van Gogh’s letters to his brother (read by John Hurt, whose recent passing we mourn). German filmmaker Susanne Ofteringer’s only work, Nico Icon (1995), recounts the life and times of another gifted and occasionally tormented artist. Yet another landmark portrait, Thomas Reidelsheimer’s Rivers and Tides: Andy Goldsworthy Working With Time (2001), takes an altogether different (and equally inspired) tack by depicting the process of creation (and destruction).