When history professor Stephen Mucher attended a protest at Los Angeles International Airport in the wake of President Trump’s immigration ban affecting seven Muslim-majority countries, he was pleasantly surprised when the crowd started singing the U.S. national anthem.

“We ended up breaking into song, and it suggests there’s some longing in us to claim this at a time where we feel our values are under attack,” says Mucher, who serves as the director of Bard College’s Master of Arts in Teaching program in Los Angeles.

The experience in January inspired Mucher to reflect on the legacy of “The Star-Spangled Banner” and its relevance today. But instead of focusing on the first verse, whose lyrics, Mucher believes, say a lot about the flag but not a lot about the Constitution, the professor turned his attention to the fifth:

“When our land is illum’d with Liberty’s smile,

If a foe from within strike a blow at her glory,

Down, down, with the traitor that dares to defile

The flag of her stars and the page of her story!

By the millions unchain’d who our birthright have gained

We will keep her bright blazon forever unstained!

And the Star-Spangled Banner in triumph shall wave

While the land of the free is the home of the brave.”

A stanza for a country divided

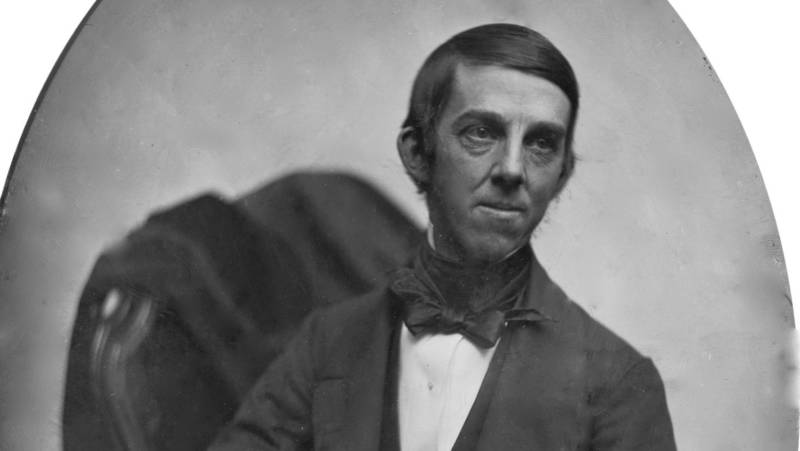

Poet Oliver Wendell Holmes penned his fifth stanza in 1861 — 47 years after Francis Scott Key’s original verses — when the U.S. was in the grip of civil war. It circulated widely in the north during those years of conflict, but eventually retreated from public view. “He wrote that fifth verse, I believe, with real sorrow at what was happening to his country,” Mucher says. “The divisions we had in this country in 1861 are similar to what we have now.”

The country was of course actually at war back then. But Mucher believes this obscure stanza, written more than half a century after Francis Scott Key penned the other four, speaks more urgently than the first verse to the politically divisive times we live in today.