In the last several months, the shifting socio-cultural landscape of the San Francisco Bay Area has become the focus of the international media, primarily in response to the rise of new technology and its aftereffects. Protests over tech commuter buses as potent symbols of gentrification and displacement, and scuffles among strangers in public spaces over Google Glass and its invasive surveillance technology have become San Francisco icons in the media. Suddenly, all eyes are on San Francisco as the center — or, perhaps, epicenter — of technology’s quaking authority over the 21st-century global community. In this regard, the city of San Francisco (really the greater Bay Area) has become a test case on the impact of rapidly escalating, brand-spanking-new wealth and its relationship to new technologies, privacy, public resources and social infrastructures. San Francisco has become a cautionary tale: Everything happening here can happen wherever else technology companies are setting up shop, which is everywhere. This article is the first in a series that will explore how this shifting terrain is dramatically impacting the livelihood of artists.

But, first, why should anyone care that the Bay Area is changing? So what if some tech entrepreneurs are sitting pretty with the 1%? Wealth disparity is nothing new, and cities change all the time: people leave, people arrive, businesses launch, businesses fail. It’s all a cycle. Even this current dot boom is part of a cycle of booms and busts in a community long focused on booming. And yet this time is different, in part because of the devastating impact new wealth is rendering on the fragile infrastructure of San Francisco’s homegrown art scene and its artists, as well as small businesses, nonprofits, advocacy organizations, lower income communities, families with children, immigrants, the mentally ill and homeless, and the generally disenfranchised.

Last week, longtime San Francisco Chronicle art critic Kenneth Baker wrote an article about the recent displacement of galleries due to exponentially inflated rents. He noted, “As far afield as Toronto and London, mid-level art gallery businesses face extinction by fast-growing, cash-rich enterprises hungry for office space in top locations.” Faced with an abrupt change in location, some galleries consider reinvention, while others simply disappear. (See KQED’s article on gallery closures and the ongoing Priced Out series for more.)

Recently Rena Bransten, George Krevsky, and Patricia Sweetow Galleries were priced out of their downtown locations at 77 Geary. Still others have closed in the past few years, including Don Soker (evicted and looking for a new space), Eli Ridgway, Guerrero Gallery, Marx & Zavaterro, Michael Rosenthal, Togonon Gallery, Triple Base, and Queens Nails. In Oakland, Mama Buzz closed in 2012, Swarm Gallery shuttered last year and Hatch Gallery announced its eviction this month. The absence of these physical spaces is a loss in the larger scheme of things, whether the individual galleries were popular or not. Galleries offer culture, community gathering spaces, and space for discourse, while exporting local artists and importing new ideas — all free to the viewer. In a conversation for this article, recent Guggenheim Fellow artist Michael Arcega, formerly represented by Marx & Zavattero, speaks of a familial sense of loss in the wake of the gallery’s closing, “So long as I kept making work that was relevant, they supported me and made an effort to create a support structure for my work. It’s very different now without that.”

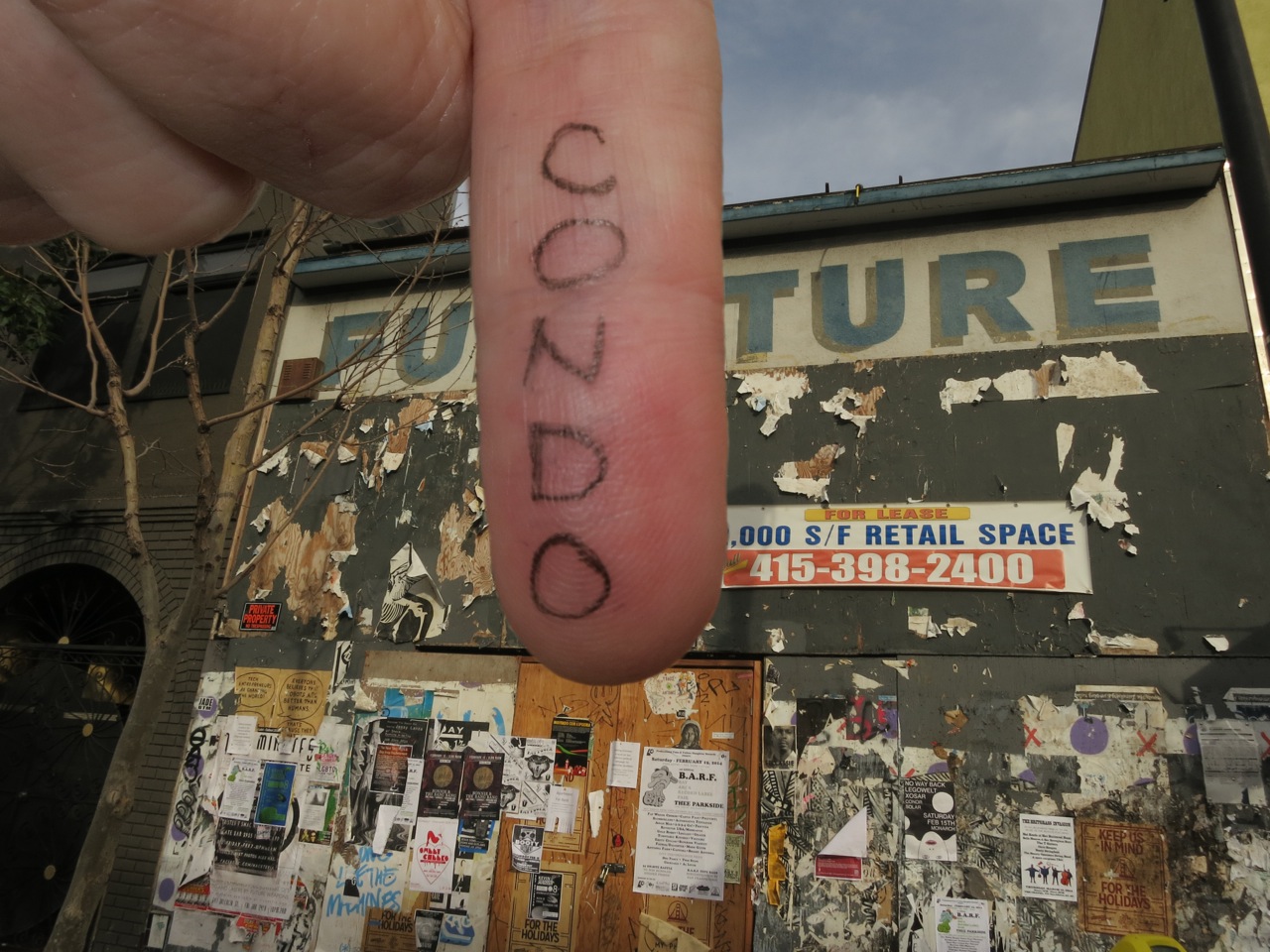

Recently several prominent galleries have also relocated away from walk-able, BART-adjacent areas of downtown to less accessible reaches of the city in Potrero Hill, including Brian Gross, Catharine Clark, George Lawson, Jack Fisher, and Hosfelt galleries. Adobe Books, and the eponymous Adobe Books Backroom gallery, relocated after an extensive rent hike last year. The Thing Quarterly owners Jonn Herschend and Will Rogan contemplated going out of business after losing their lease and finding rental prices untenable in the Mission. They ended up finding new offices in the Tenderloin.