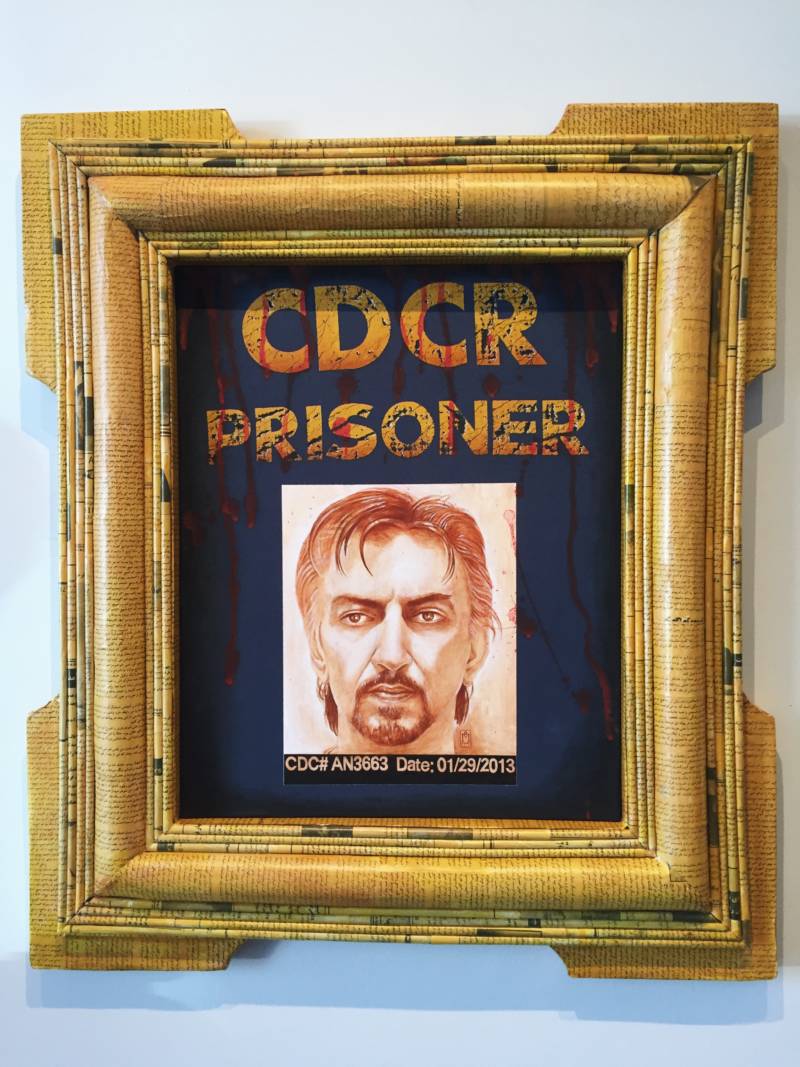

Two massive paintings by Oakland artist Dave Kim meet the viewer at the entrance to Vessel Gallery’s Excuse me, can I see your ID?, an exhibition that aims to unravel over-simplified understandings of Asian-American identity.

The first is a rendering of a young Korean-American boy — actually, Kim himself — sporting a small cowboy hat and playfully pointing two toy guns at the viewer, a little holster attached to his jeans. Per Kim, it’s called “Double Exposure” in part because the reference photo is literally double exposed — and you can see the effect in the painting as well, as a streak of light running across the bottom. But the title works, too, as a short poem about the experience of growing up between two cultures and the youthful naiveté of thinking they could be reconciled with a costume.

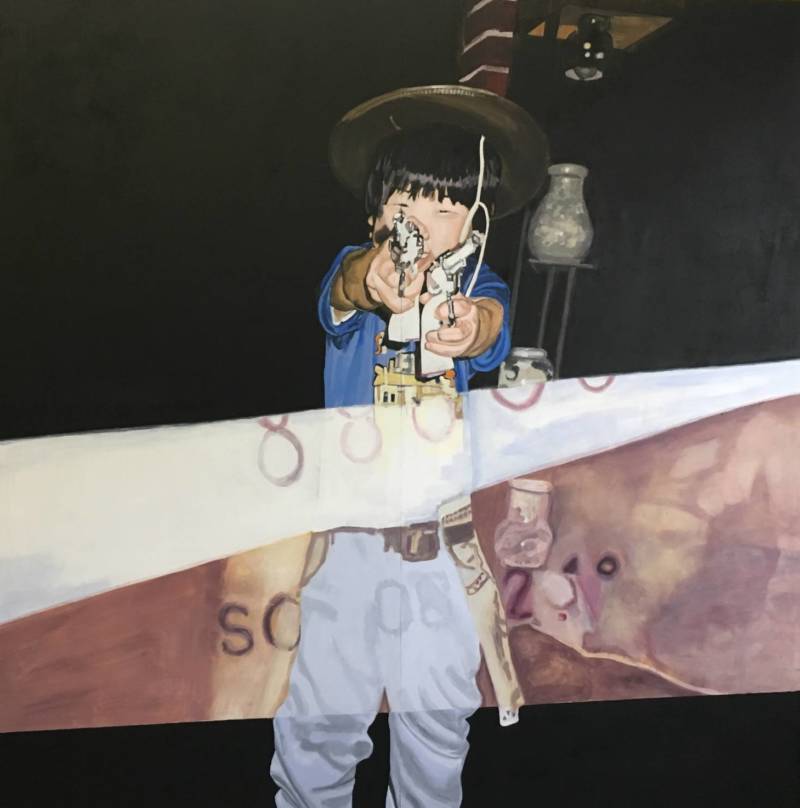

The second is a reflection on Kim’s teen years, during which he joined a Filipino gang in Los Angeles called Maplewood Ave. Jefrox. To those who can decipher them, the aerosol scribbles on the gray-painted background tell a story. There’s the name of the gang, RIP messages to two lost members, a diss by a rival gang, then a rebuttal by Jefrox. At the reception for the show, Kim points out that he joined the Filipino gang because there were no Korean gangs, just as the Filipinos had joined Latino gangs before they had their own. “Even though we’re Asian, we took on the characteristics of Latino gangs in every way, from claiming a neighborhood, to the attire and even the language we used,” he writes in his artist statement. “I think the thing to remember is that I joined it not to be violent or become a criminal, but to be a part of something, to find belonging, importance — find purpose.”

Kim chuckles as he points out that these days, he’s the one having to paint over tags that show up on his home in West Oakland — even though, when he went back to paint that aerosol piece, the script didn’t take long to come back to him. Now, he says, he tries to find belonging in other ways.

Kim’s pieces are an effective primer for the show in part because of their reflection on seeking acceptance and attempting assimilation. But they’re perhaps most appropriate because they surprise — by embracing the slipperiness of Asian-American identity and the complicated ways in which Asian-Americans sometimes adopt tropes belonging to other identities in order to fill out their own relatively ambiguous cultural slates. That fluidity was, in part, what curator Lonnie Lee was trying to get at when she started developing the show two years ago.