Do you read the comments? I read the comments. I read them after articles on immigration specifically, because the arguments tend to trickle down to the same thing and I like thinking about patterns and semantics. With immigration, you can almost do a countdown—six or seven comments in, a common disagreement appears: are Native Americans original inhabitants or immigrants? The irate will say that Native Americans crossed the Bering Strait and so they are immigrants, and this is one way of saying the country doesn’t belong to them, as well as the country belongs to those who took possession of it.

Two books I read this month promise to take your arguments from the general to the specific: Violent Borders: Refugees and the Right to Move by Reece Jones (a history of borders, focusing among others on the US-Mexico border, Bangladesh, and Palestine) and Chasing the Harvest (an oral history of migrant workers in California agriculture). Each provide a wholly focused view on immigration.

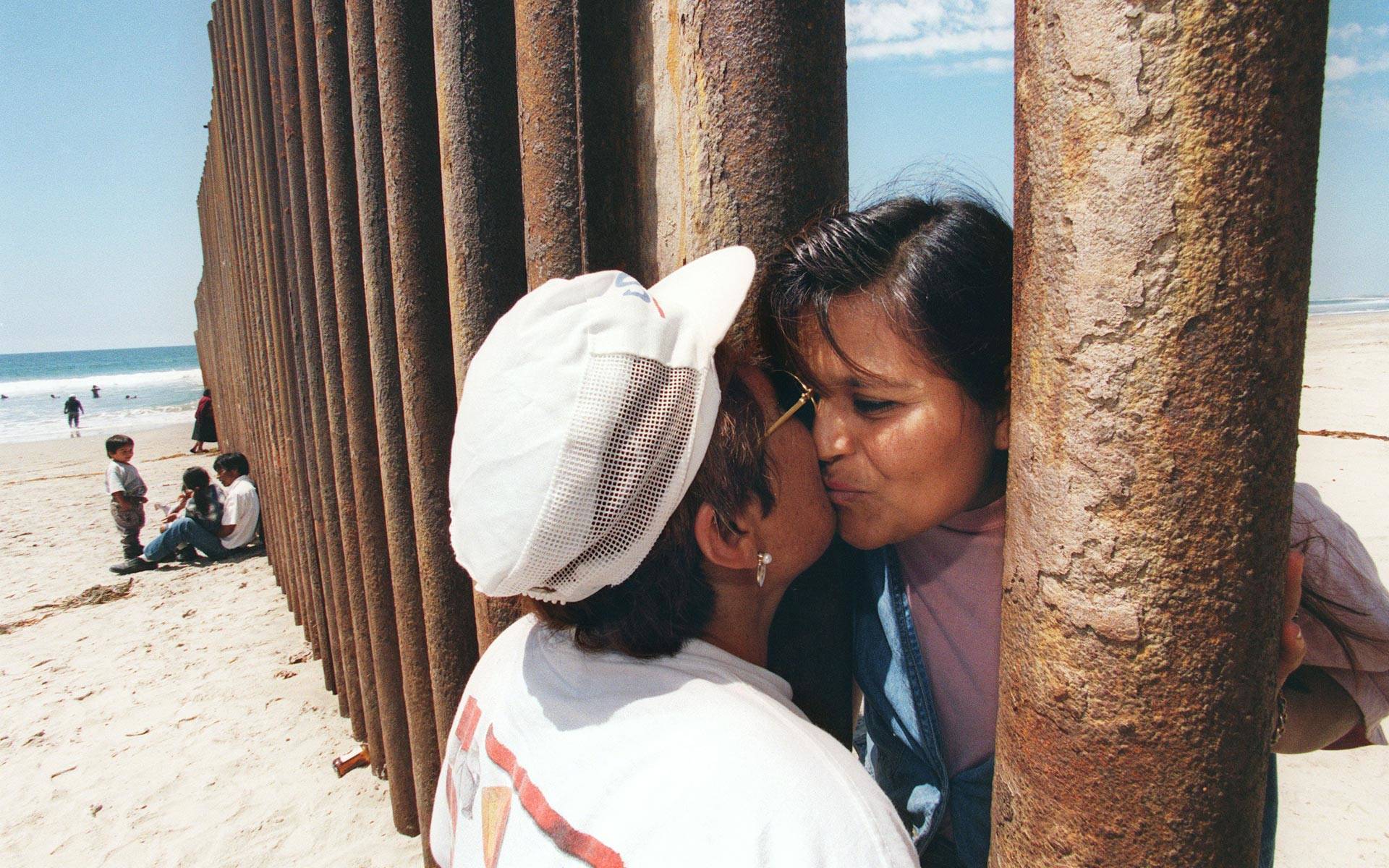

The United States is one of a few countries whose immigration philosophy is jus solis or right of land, which means that if you spend enough time on U.S. territory you have a right to citizenship. But who has that right and if it matters how they entered is our all-consuming question.

In Violent Borders, Jones provides plenty of examples of how these semantic arguments lead to inequality, isolation, racism, and institutional loss of liberty for entire groups of people. This is the case of the Rohingya, a Muslim minority in Myanmar. As recently as 1982, Myanmar (then Burma) passed a law granting citizenship to specific ethnic groups. It did not include Muslims and so, though the Rohingya never moved an inch, they became foreigners in their own land stripped of rights of labor, travel and representation in government. Myanmar claims the Rohingya immigrated from Bangladesh. Bangladesh argues the Rohingya did not originate there. The Rohingya are stateless and in limbo. They cannot even claim refugee status in another country, because having no state, they cannot prove their origin.