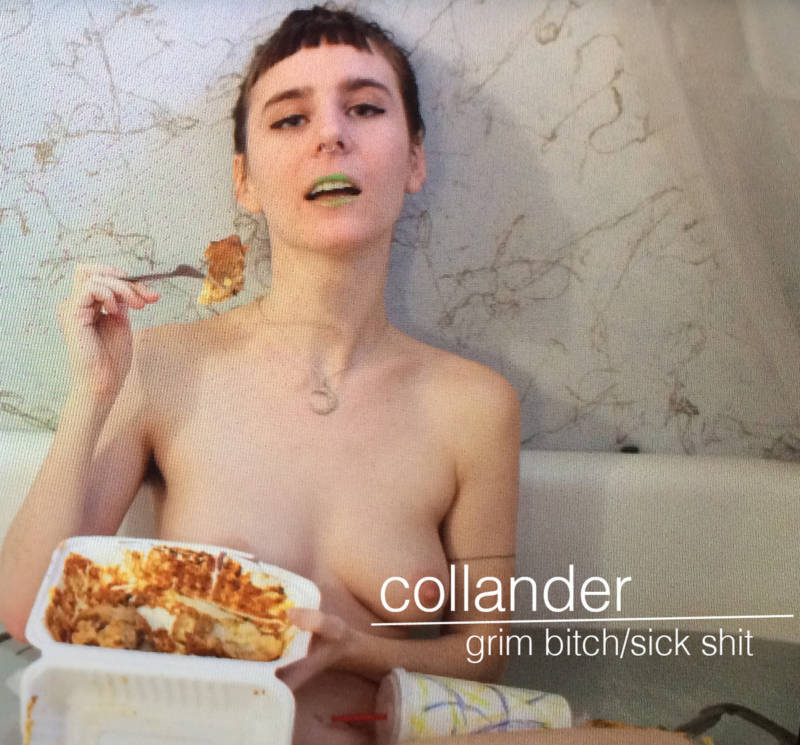

The cover for Collander’s sophomore album, grim bitch/sick shit, features Alli Yates sitting naked in a bathtub filled with floating trash eating a greasy container of baked beans. Leaning against a faux marble wall wearing chartreuse lipstick, she looks oddly luxurious, sassily owning the sickly color of her modelesque pout.

Yates, who sings over self-produced lo-fi pop beats as Collander, said that the imagery came easily to her. Being a disabled and chronically ill person who rarely leaves her home, she can often be found in the bath — and not rarely, eating. “It became this joke among my friends that I should start a series of selfies of me eating all these different dishes in the bathtub,” she laughs.

But the cover also encapsulates a bit of what Yates’ music does, which is poetically speak to the experience of being a sick femme living under late-capitalism. Grounded in a disability justice framework, Yates makes music about everything from pain to heating pads to the “medical industrial complex,” using an almost magical-realist approach to reimagining diagnoses and the sometimes-dark aspects of her daily life.

Yates first taught herself to make beats using GarageBand in 2014 during a six-month period when she wasn’t leaving her bed, resulting in five short songs collectively titled bed mongering. She eventually moved on to using a small synthesizer, sampler, and reverb pedal. Those were her tools when creating the nine tracks on grim bitch/sick shit, which she wrote and recorded over the course of three weeks early last year, when she was unpacking “varying amounts of trauma.” Initially, she told herself the music-making was only a reflective process — a low-pressure outlook that helped her finish the project despite being a perfectionist with limited energy — but eventually decided to release it online as well.

At the time, Yates was going through multiple breakups, having just left a partner as well as all of the doctors she was seeing. And the stripped-down songs reflect that ambiguous merging of romantic and medical experiences. In “blood left,” Yates’ high, shimmering voice softly sings over a pared-down composition of artificial drums and spacey gusts: “I don’t have any blood left for you/how could you still see it that way?” And in another: “Instead of empathy/you’re just medicalizing me/you’re a goblin of emotion/and I hate you.”