Eight years ago, when I first arrived in the Bay Area, I knew next to nothing about Roy De Forest and his UC Davis compatriots (including William T. Wiley, Robert Arneson, Peter Saul, the legendary list goes on). An early visit to the di Rosa collection, with its vast holdings of eccentric, cartoonish, decidedly funky Northern California art — De Forest works included — left me completely flummoxed. “What is this stuff,” I wondered. “And why would anyone collect it?” It simply wasn’t the conceptual, minimal, finish-fetish art I was used to calling art.

But over the years, something changed. The Bay Area and its history of counterculture movements, art scenes full of sardonic humor, groan-worthy puns and true camaraderie, won me over. The sunshine helped. The Oakland Museum of California’s Of Dogs and Other People feels like a personal reward for a conversion in taste.

While other Bay Area institutions double down on the 50th anniversary of a particular season, OMCA instead devotes its summer exhibition space to a Bay Area artist whose story didn’t start — or end — in 1967. Of Dogs and Other People is the wonderfully titled, long-overdue retrospective of the late Roy De Forest, whose six-decade career evades easy categorization.

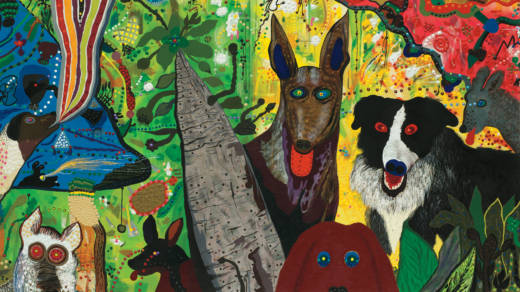

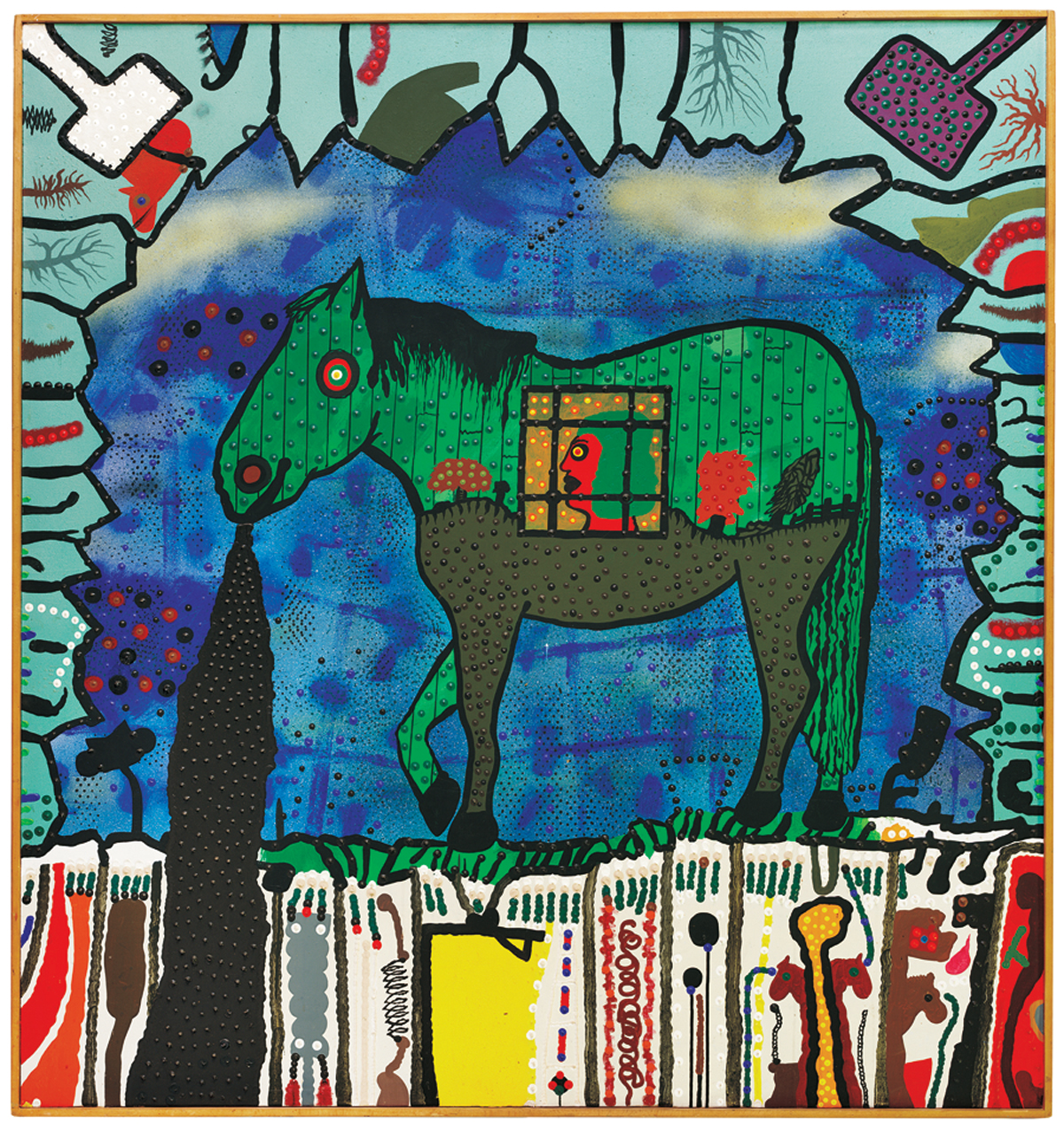

His exuberant, frenetic paintings, embellished frames and colorful sculptures capture the psychedelic energy of the 1960s as it flowed into the idiosyncratic, so-called Funk movement (which De Forest preferred to call “Nut Art”). The exhibition itself, arranged thematically rather than chronologically, gently guides viewers through a phantasmagorical world of De Forest’s own imagining: a world full of giant rabbits, indecipherable treasure maps, swirling night skies and plenty of wagging tongues.

If you’re seeking deep biographical information, historical context and critical analysis of De Forest’s work, Of Dogs and Other People, the exhibition, is not the place for that; Of Dogs and Other People, the exhibition catalog, is. Punctuated by listening stations featuring audio responses by everyone from a fifth-grader to a sword swallower, the exhibition privileges individual interpretation, guided by wall text that poses introspective questions rather than explanations of the specific whats and whys of a given piece of art.

For those used to spending more time reading a chunk of wall text than looking at the work of art it describes, this curatorial approach may be frustrating. I found it liberating.