On Aug. 10, 1966, as the black community in San Francisco reeled from the sudden death days prior of the Fillmore District’s Charles Sullivan, a different crowd — young, mostly white — convened in the neighborhood. Their purpose? To see Sam the Sham & the Pharaohs perform at the venue Sullivan had once operated, the Fillmore Auditorium.

The show was promoted by an upstart rock impresario whose name is now virtually synonymous with the Fillmore and the ’60s rock scene in San Francisco: Bill Graham. It marked not just a turning point for the storied venue, now recognized as the center of the psychedelic era, but a microcosm for the transformation of the Fillmore district, over which Sullivan had presided for years with widespread respect and influence.

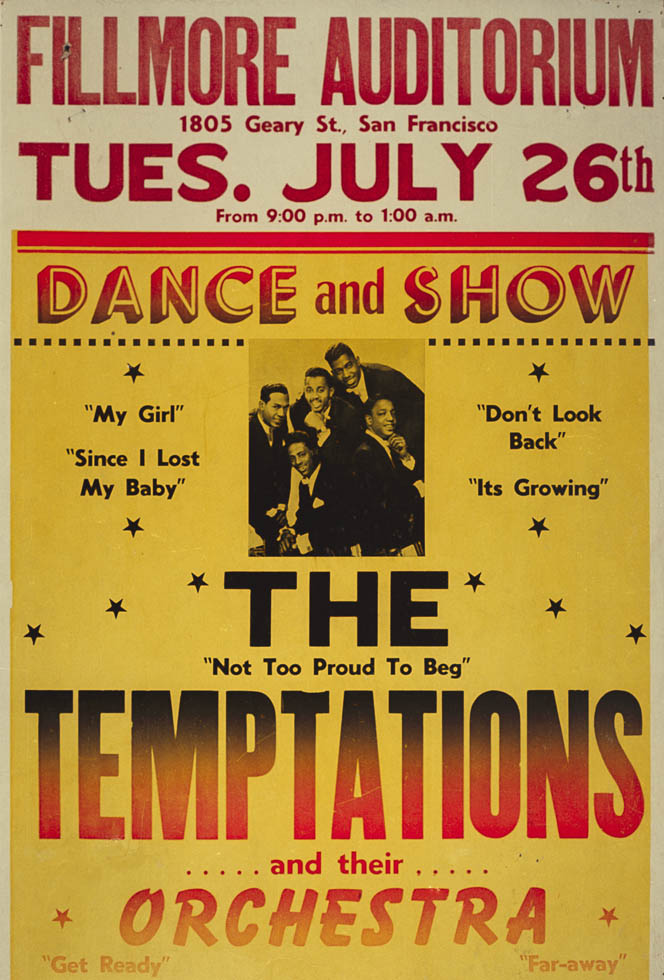

A concert mogul with a nightlife empire in the Fillmore district, Sullivan was busy arranging massive shows for artists such as the Temptations just days before he was found dead from a point-blank gunshot wound to the heart in 1966. Newspapers reported on the neighborhood memorial service that August, when hundreds gathered to eulogize who reports called one of the wealthiest black men in the west.

“A civic and cultural leader is killed and it sends shockwaves throughout the community,” says historian and radio host Rickey Vincent, of the timing of Sullivan’s death. “But that becomes a silent narrative, because it coincides with this explosion of countercultural activity.”

A not-so-peaceful transition

Bill Graham, of course, would go on to turn that explosion of countercultural activity into a career. A Capricorn with a clipboard, Graham beckoned the 1960s youth culture upstairs to the Fillmore Auditorium in all its extravagance: dissociative drugs, newfangled lightshows, and a lot of white guitarists enamored of a kaleidoscopic blues. But the liberationist riot of sight and sound arrived amid gathering nastiness for residents of the neighborhood below, a black cultural center embattled by the bulldozers of redevelopment.

Sullivan’s death and Graham’s ascent meant outgoing jobs and black entertainers, and incoming hippies. The swift violence that felled the powerful figure — coupled with the police’s contentedness with their unlikely suicide theory — sowed more sadness and fear in a neighborhood that already appeared besieged. Rumors even emerged that Graham was somehow involved in the death of Sullivan, whose murderers remain unknown.

Graham’s autobiography Bill Graham Presents: My Life Inside Rock and Out admiringly remembers Sullivan, yet Graham has also said that he “discovered” the Fillmore. The Los Angeles Times reports that Graham “refurbished” the Fillmore. And the venue’s website credits Graham with instigating a “musical and cultural Renaissance” at the Fillmore. Summer of love literature often omits that, as longtime neighborhood resident Danny Duncan has said, “African Americans — we used the Fillmore Auditorium before Bill Graham took it.”

Graham operated the Fillmore Auditorium for two and a half years, and later opened the Fillmore West and Fillmore East. “The Fillmore Sound” became synonymous with the “San Francisco Sound,” referring to the inception of psychedelic rock. Graham died in a helicopter crash before the venue reopened in 1994, and the Fillmore today heavily honors the famed rock impresario (and his apple giveaways for concertgoers).

“You can go to the Fillmore now and see fanciful posters of rock shows from back in the day, and they give a sense of history that’s joyful and fun and irreverent and that begins in 1966,” says Vincent, who moderates a panel series this month on the “black psychedelic impulse” at the California Historical Society. “If you walk in the building, that’s what you get, the impression that the Fillmore began with Bill Graham.”

‘Wall-to-wall people’

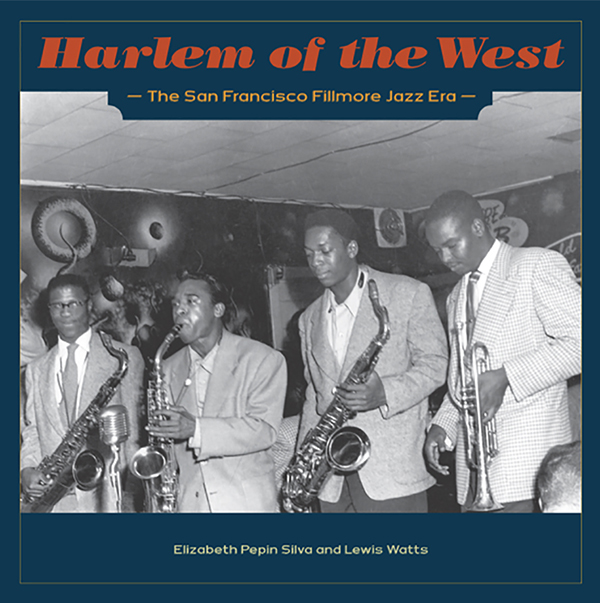

But in the black community, the Fillmore had been bustling for many years. “From Hayes to Post, it’d be wall-to-wall people on weekends,” recalls Lewis Watts, co-author with Elizabeth Pepin-Silva of the recently republished book about the Fillmore, titled Harlem of the West. “People would come Friday afternoon and stay until Sunday night.”

This was partially a result of the black population in San Francisco ballooning during World War II, when jobs in the local defense industries lured workers from the South. Housing discrimination restricted the newcomers predominantly to the Fillmore district and surrounding Western Addition, where the wartime internment of a robust Japanese community left vacant storefronts and Victorians. Black San Franciscans, few before the war, numbered more than 42,000 by 1950.

This new population transformed the Fillmore into a cultural center remembered as “Harlem of the West,” with more than two dozen nightclubs in a square mile: the Champagne Supper Club hosted Billie Holiday’s San Francisco stage debut; the back room at creole restaurant Jackson’s Nook accommodated the spillover from nearby Jimbo’s Bop City; and the basement spot known as Estelle’s After Hours Place let people party until Jack’s of Sutter opened for its 6am Sunrise Jazz Session.

As described in Harlem of the West, much of the area’s nightlife was presided over by Sullivan, an entrepreneur known for sharp suits and a loose billfold. His empire encompassed liquor, jukeboxes, and vending machines. He bankrolled Jimbo’s Bop City, renowned for lively jam sessions, and operated the lounge of the Booker T. Washington Hotel, choice residence for visiting black celebrities. And in 1952, Sullivan snagged the lease of a segregated roller-skating rink at the neighborhood’s center and rechristened it the Fillmore Auditorium, presenting artists such as Duke Ellington and Count Basie.

From slavery to ‘The Mayor of the Fillmore’

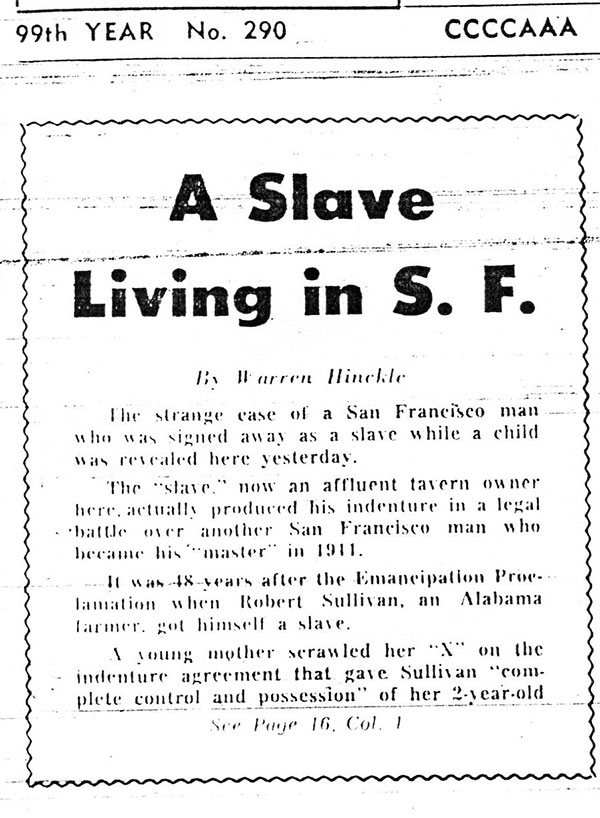

Humble does not begin to describe Charles Sullivan’s origins. “It was 48 years after the emancipation proclamation when Robert Sullivan, an Alabama farmer, got himself a slave,” reported the late Warren Hinckle in a page-one San Francisco Chronicle story from 1963. “A young mother scrawled her ‘X’ on the indenture agreement that gave [Robert] ‘complete control and possession’ of her two-year-old.”

The two-year-old was Charles, whose history came to light in a legal dispute after Robert, elderly and living in San Francisco, attempted to invoke parental rights. Charles had come to the west coast in search of work as a machinist. When union racism blocked him from the industry, he chauffeured on the Peninsula, and eventually opened a bar and restaurant in San Mateo. As the Western Addition filled with black workers, Sullivan eyed opportunity. Fillmore Street was known as Swing Street, and the once-indentured man set out to become the people’s mayor.

“He was culturally seeding the black identity into San Francisco like few other people,” says local artist Harry Hall, whose research on Sullivan culminated in a one-man play, Blues for Charles, which premiered in 2014. “For those years the Fillmore was a mecca. I mean, before Charles we [black people] weren’t even allowed inside.”

A neighborhood decimated

Yet for almost the entire lifespan of the Fillmore as a bustling hub of blues and jazz, new trends in urban planning conspired with racism to end the music. The San Francisco Redevelopment Agency was empowered to acquire properties on the promise that, through razing and rezoning to increase density, they’d improve quality-of-life and reduce housing costs.

One of the first determinations of the agency was that huge swathes of the Fillmore and Western Addition were hopelessly “blighted,” and slated for demolition. As a 1999 KQED documentary on the Fillmore points out, official documents of the time included “non-white population” as one condition of blight.

Much of the neighborhood was earlier “red-lined” on maps issued by the government to banks, meaning creditors were advised not to issue home loans. This produced a population of predominantly renters. Agency officials promised them that, if they left, they could return later to better, cheaper homes. But that didn’t happen. Agency certificates professing a right-to-return, issued in thousands by agency, remain useless.

The neighborhood lost 883 businesses and 4,729 households, according to the agency’s own figures. Within the redevelopment zone was nearly every nightclub, juke joint, and bar. Much of them perished to accommodate a sleek new Geary Boulevard, widened so that residents of western neighborhoods could swiftly commute to work downtown.

Among other landmarks, the Booker T. Washington Hotel was bought and destroyed by the agency; the lot remained empty for decades, until the construction of a large Safeway store. Bobbie Webb recalls in Harlem of the West that his band, Bobbie Webb and Company, played the last show there in the Sullivan-operated lounge. “We played a great gig that night, and the very next day they began demolishing the hotel,” he recalls. “It was so sad because it wasn’t falling apart. I guess it was just in the way.”

A ‘shining light for every black artist’

Sullivan was one of few black businessmen who weathered the storm of redevelopment. “He was one of the top promoters of African-American artists in the area,” reckons Hall. “And he seemed to really be crossing over.”

By the time he encountered Bill Graham in 1965, Sullivan was organizing entire coastal tour-routes for icons of the day. Some of his bookings, such as James Brown, were too big for the Fillmore, so he’d book at the 12,000-capacity Cow Palace arena in Daly City. In other words, he was already doing in the mid-’60s what Graham would become famous for in the next two decades.

The scope of Sullivan’s business, coupled with the declining black population in the Fillmore, perhaps helps explain why he allowed Bill Graham to throw a benefit gig for the provocative San Francisco Mime Troupe, then battling obscenity charges, on December 10, 1965. Headlining above a newly named Grateful Dead was Jefferson Airplane. Graham, who’d been suggested the venue by Chronicle critic Ralph Gleason, says in his autobiography that he’d never been to the venue: “I knew nothing about it.”

Graham struck a deal with Sullivan for off-nights. Eventually, according to Graham’s autobiography, the police pressured Sullivan to stop lending his coveted dance permit to the upstart promoter, who’d been repeatedly denied one of his own at City Hall. “No, no, no. I just ain’t going to let this happen now,” Graham recalls Sullivan saying one day. “You just go back downtown, man. And you beat those white motherfuckers.”

Graham marshaled support from business owners, attorneys, and various city power brokers for his bid to acquire a dance permit, and, after a crucial push from the Chronicle’s editorial board, prevailed in June of 1966. “A few months later, Charles Sullivan got himself killed. He had a bad habit of always carrying a roll of money with him,” Graham says in his book. “Had that not happened, I think I would have done anything Charles wanted. Just out of gratitude.”

What followed is familiar, especially amid this year’s rosy retrospectives of the Summer of Love. So what else should we remember about the Fillmore Auditorium? “That it was a shining light for every black artist who dreamed of making it in the music business in San Francisco,” says Hall.

“If you feel soul in there today it’s because of Charles, and if Bill Graham was alive I bet he’d tell you the same thing.”

All images courtesy of ‘Harlem of the West,’ by Elizabeth Pepin Silva and Lewis Watts. A new, updated edition of ‘Harlem of the West’ is available in hardcover ($60) and softcover ($35), plus $5 postage, by ordering via Paypal or emailing otwfront@gmail.com.