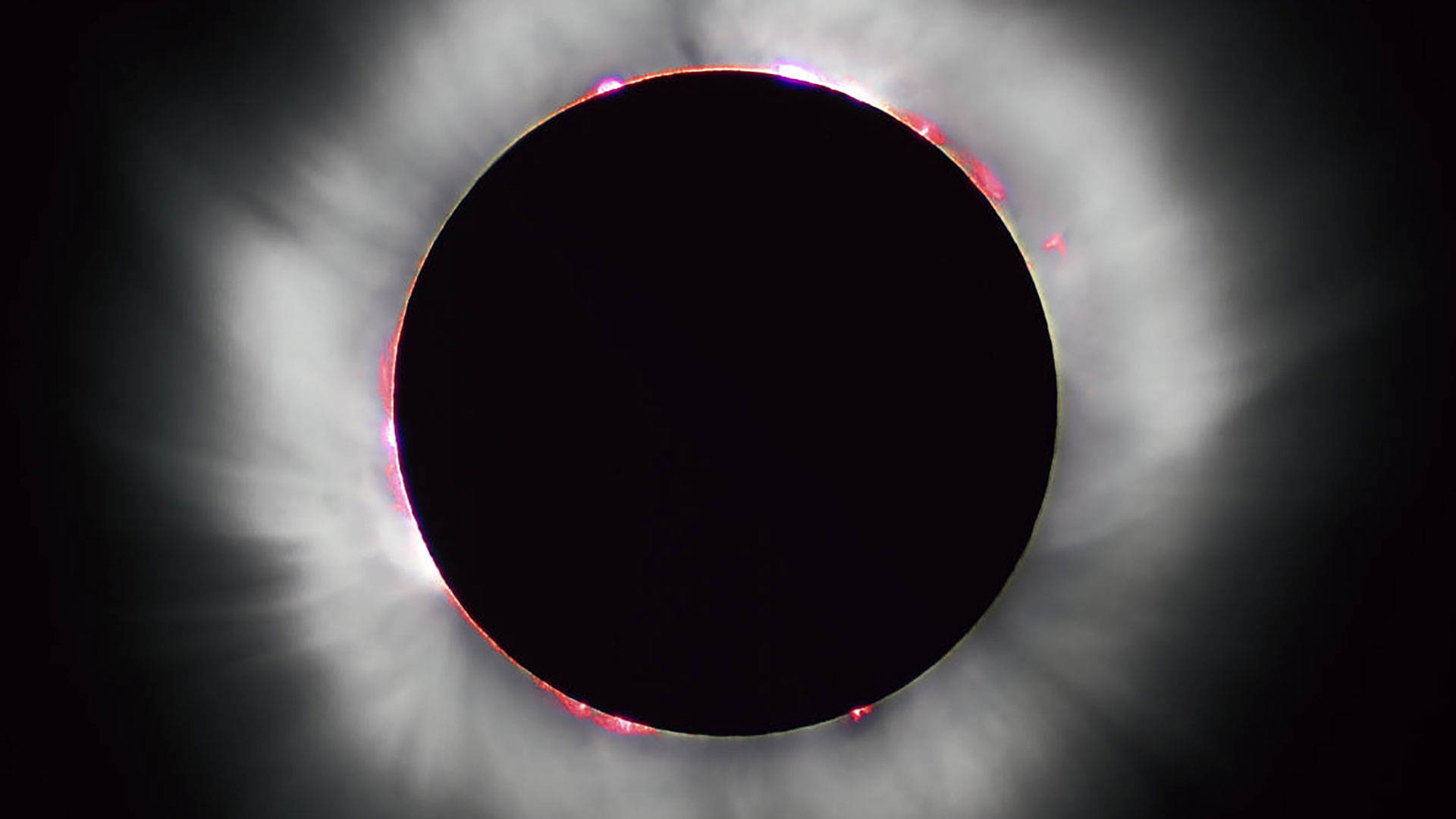

What with the stunning eclipse, the troubling interactions of President Trump and Kim Jong-un, the daily fraying of truth, the melting arctic, and white supremacists gathering in Berkeley and San Francisco, the end of the world comes easily to mind.

The poet Czeslaw Milosz imagined the end of the world as an unnamed destruction not remarked upon by the happy porpoises that jump in the sea, the women walking through fields, nor the vegetable peddlers that shout in the street. Instead, he writes:

Only a white-haired old man, who would be a prophet

Yet is not a prophet, for he’s much too busy,

Repeats while he binds his tomatoes:

There will be no other end of the world,

There will be no other end of the world.

Heaven is All Goodbyes by Tongo Eisen-Martin is not a book about the end of the world. But the author’s second poetry collection, released by City Lights, has an feeling of being written from the brink of cataclysm.

In Eisen-Martin’s verse, black men get out of cars “against white supremacy,” Europe reaches America “carrying headaches and mirrors,” alarms are made of gold, and in perhaps the most succinct description of our national circumstance, “People are newspapers / and actors / And the congregation is all going to die in character.”

I read this book while in the bathtub, with my ears below water, like I was listening to a pristine record with headphones. Musical references pepper this collection, so it is no wonder I had music in mind. There is a sublime cadence in Eisen-Martin’s work that is polyphonic, gritty, and unexpectedly fragile, like jazz. These poems yell, shriek, whisper, mumble in a mosaic of disenfranchised voices pondering police brutality, guns, the power of community, the terror of inherited addiction, and the cold nature of a city that blankets the poor and colored in oppression.

In a recent interview for the Poetry Foundation, Eisen-Martin

In a recent interview for the Poetry Foundation, Eisen-Martin