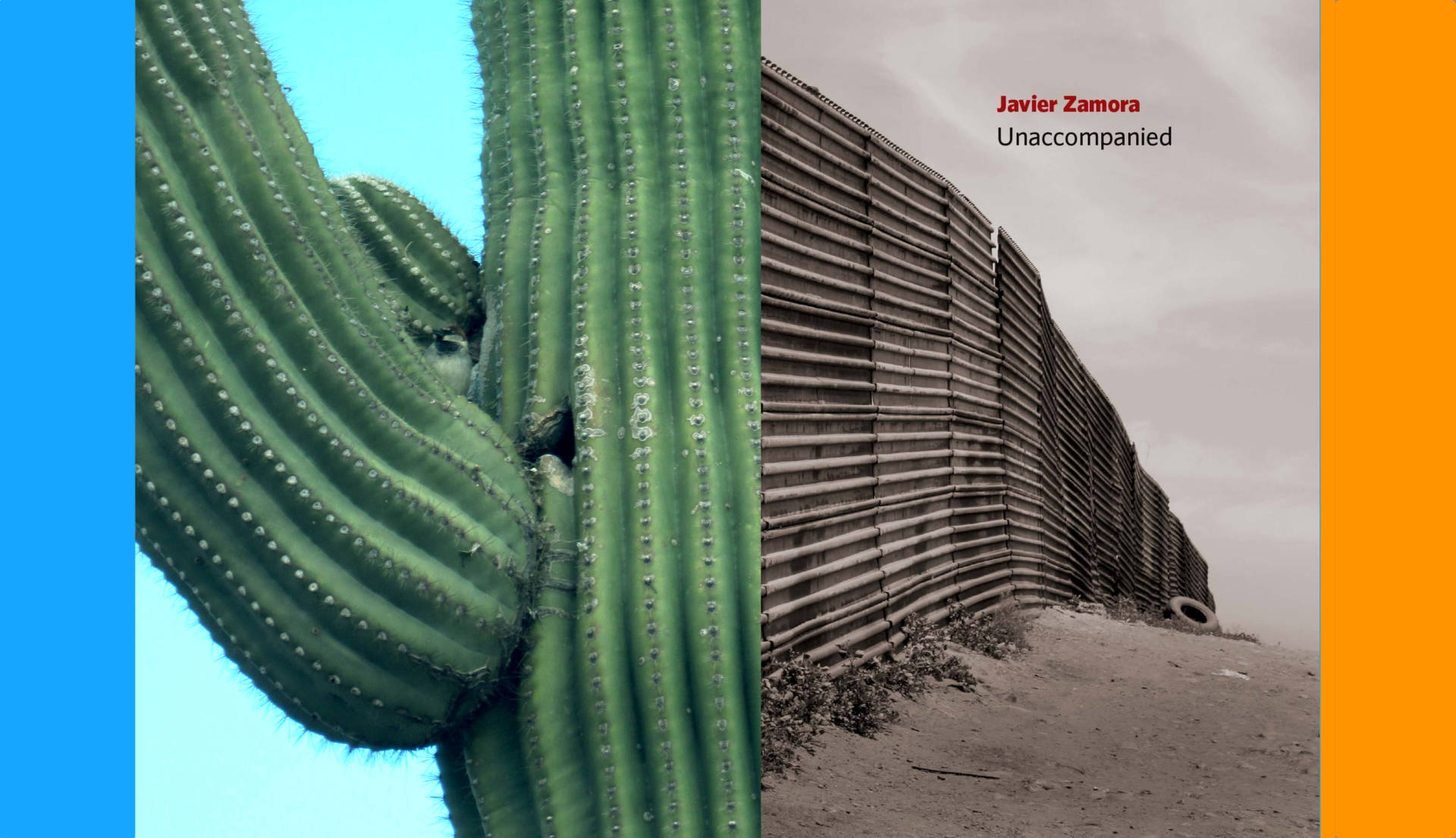

This past Tuesday night at Galería de la Raza, a capacity, standing-room-only crowd filled the space for the full moon celebration of the release of Unaccompanied by Javier Zamora. A book that speaks to the Zamora’s experience of crossing multiple borders from El Salvador to the United States at nine years old to be reunited with his parents, Unaccompanied is a collection populated by deserts, border violence, a family’s desperate claim to survive, and the conjuring up and remembrance of a country left behind. At Galería de la Raza, the scent of pupusas and cheese filled the gallery. There was a kindling air of celebration.

Nothing belied the unrest the city had been in all day long.

Three miles away in downtown San Francisco, protesters that had congregated all afternoon in growing numbers in front of the Federal Building had shut down one lane of traffic and were marching down Market Street, chanting We are people, we are not illegal, no! Earlier in the day, the Trump administration had officially announced that the DACA program — which gives temporary legal status to undocumented immigrants brought to the U.S. as children, and allows them to work and get an education — would be phased out in six months’ time.

Not oblivious to the events going on outside the Mission, patrons at Galería de la Raza gathered with a different sense of urgency — to hear and celebrate a young voice versed in borders, and the effects of borders on the self and family.

Javier Zamora’s Unaccompanied asks: Is fleeing from danger a crime? Is being driven by spotlights and vans into desert trees and into hiding a crime? The government says yes. Unaccompanied begs to differ.

It was dusk for kilometers and bats in the lavender sky,

like spiders when a fly is caught, began to appear.

And there, not the promised land but barbwire and barbwirewith nothing growing under it. I tried to fly that dusk

after a bat said la sangre del saguaro nos seduce. Sometimes

I wake and my throat is dry, so I drive to botanical gardensto search for red fruits at the top of saguaros, the ones

at dusk I threw rocks at for the sake of hunger…”

Zamora’s stunning collection, sprinkled with some Spanish, is deceptively prosaic. In Unaccompanied, the politics of border-crossing take a backseat to the brutal realities that such a journey would entail. There is hunger, there is thirst, there is the saguaro, and bats. There are fruits. There is desert-found kindness among strangers. There are tight spaces: white vans and boats to travel in, and cells when found and captured.