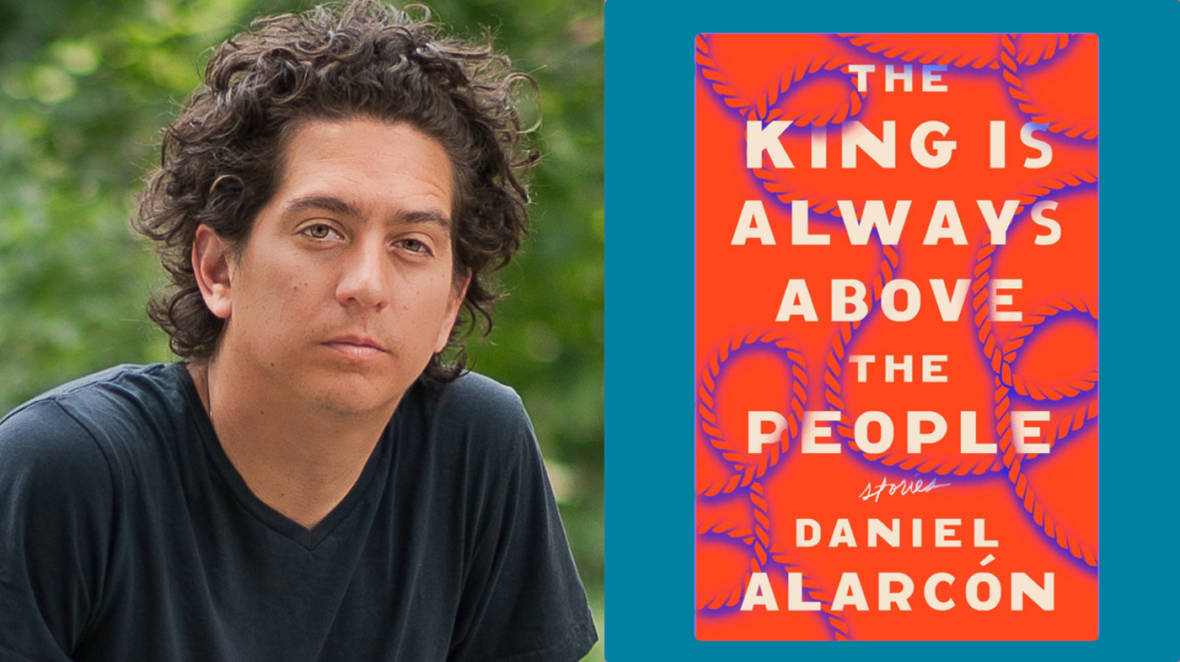

Daniel Alarcón’s latest story collection, The King is Always Above the People, is a modern study of self-deception — that is, the capacity to know and to simultaneously suppress.

The male protagonists in the volume’s 10 stories wander aimlessly, avoiding their past, as if terrestrially shipwrecked. They are adrift in an unnamed country that reminds me of Peru, but the specific place is besides the point. The pressing matter is the pull of our own subterfuge. These stories seem to ask in a chorus: in all the small and fragile ways in which we make believe, how are we undone by our own pretense?

It is enticing to abandon a life, to engage in reinvention, start anew. At least once in our lives we gather our things and move cities, countries, hemispheres. We try a new nickname, pick up affectations, other ways of speaking, and we pretend this newness is old, has always been there.

This book brought to mind how, a few years ago, as my heels clicked on the metal floor while getting on an underground train, I decided — I mean, I accepted — the self-assigned role come to me from the ether of newly-single woman. Entering the train had been like coming on stage. I had been married for some years, but mid-stance I mustered up the level of mysterious ennui I thought the part required. I lowered down to the seat as I thought a newly single woman might, with a lightness that might be too tender for a public place. Then, staying in character, I fished out my book. I licked my finger before turning the page (a foreign gesture). I read the sentences in the mind of a single woman, and then, after a few stops, I stood. I exited the train and it was curtain call: my role was over.

The King is Always Above the People imagines a world where the pretending doesn’t come to an end. It continues. In the title story, a young man arrives to a new town, and for no obvious reason misrepresents himself as an orphan who is saving to go to college. In “The Lord Rides a Swift Cloud,” a man at the end of a long trip tires himself out from acting unlonely for strangers, and in “The Auroras” a man falls into playing house with a married woman whose husband is away.