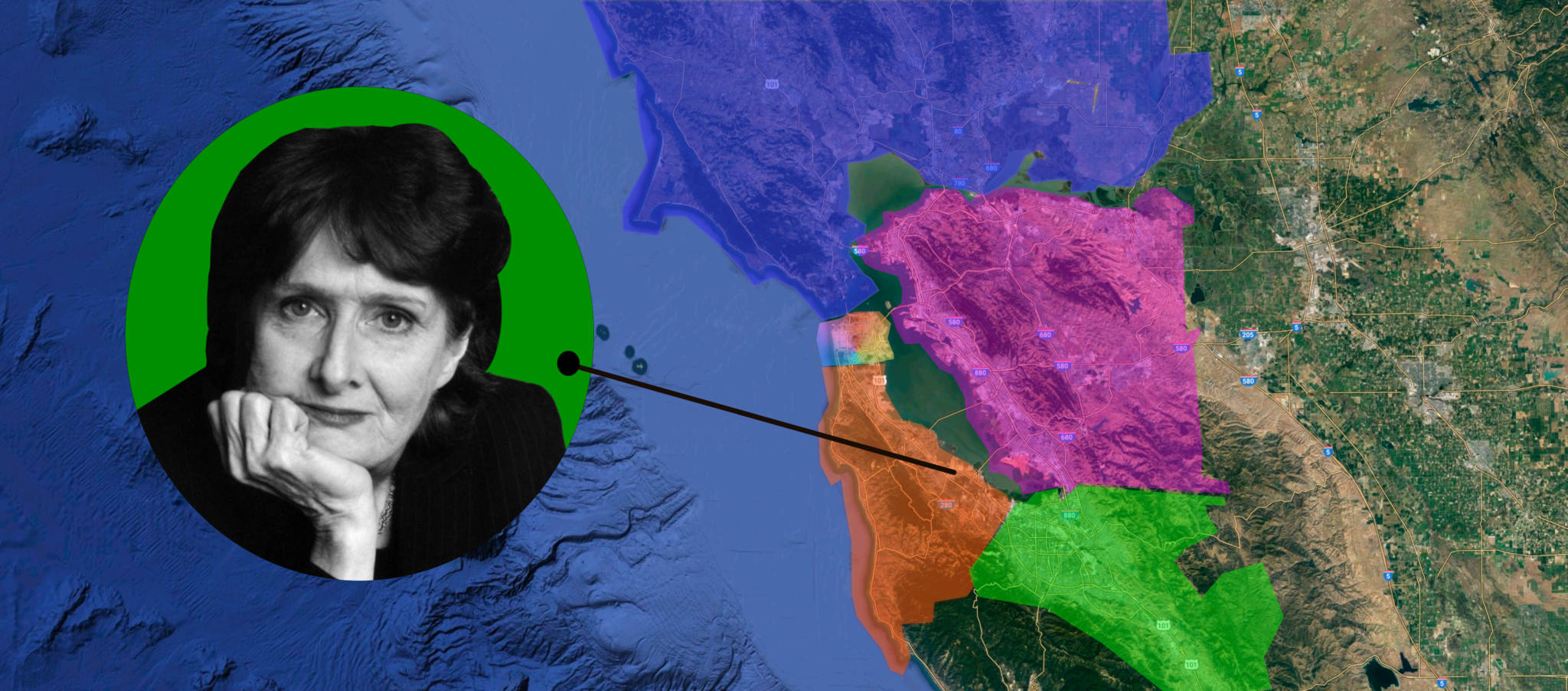

Silences was published in the year my second daughter was born, when I was stumbling between language and new circumstances. Olsen’s radical compassion, her anti-romantic critique of the inevitability of talent has stayed with me ever since. A lot of writing has mattered to me. Some has been shape-shifting. But very few books are also guiding spirits. For me, this was one of them. — E.B.

Eavan Boland’s latest poetry book, A Woman Without a Country, is now out on paperback.

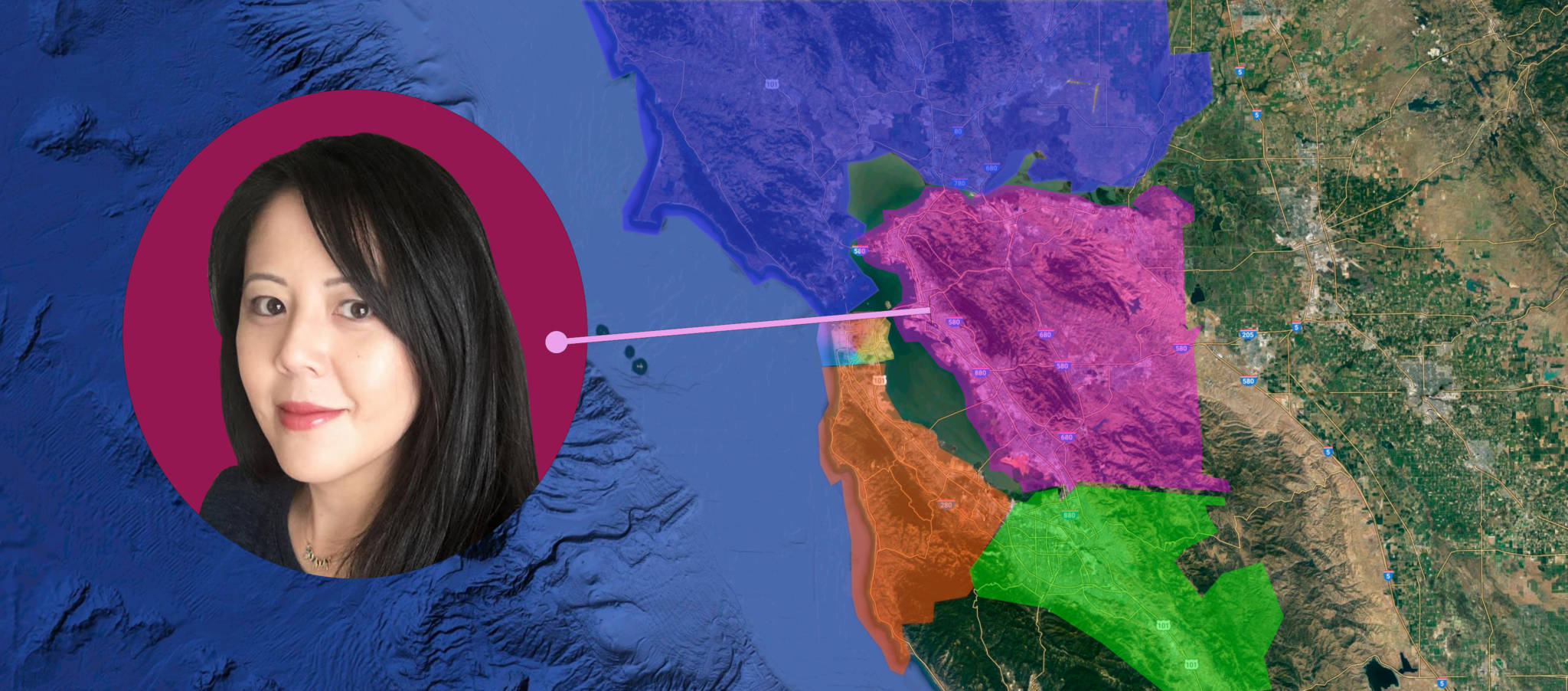

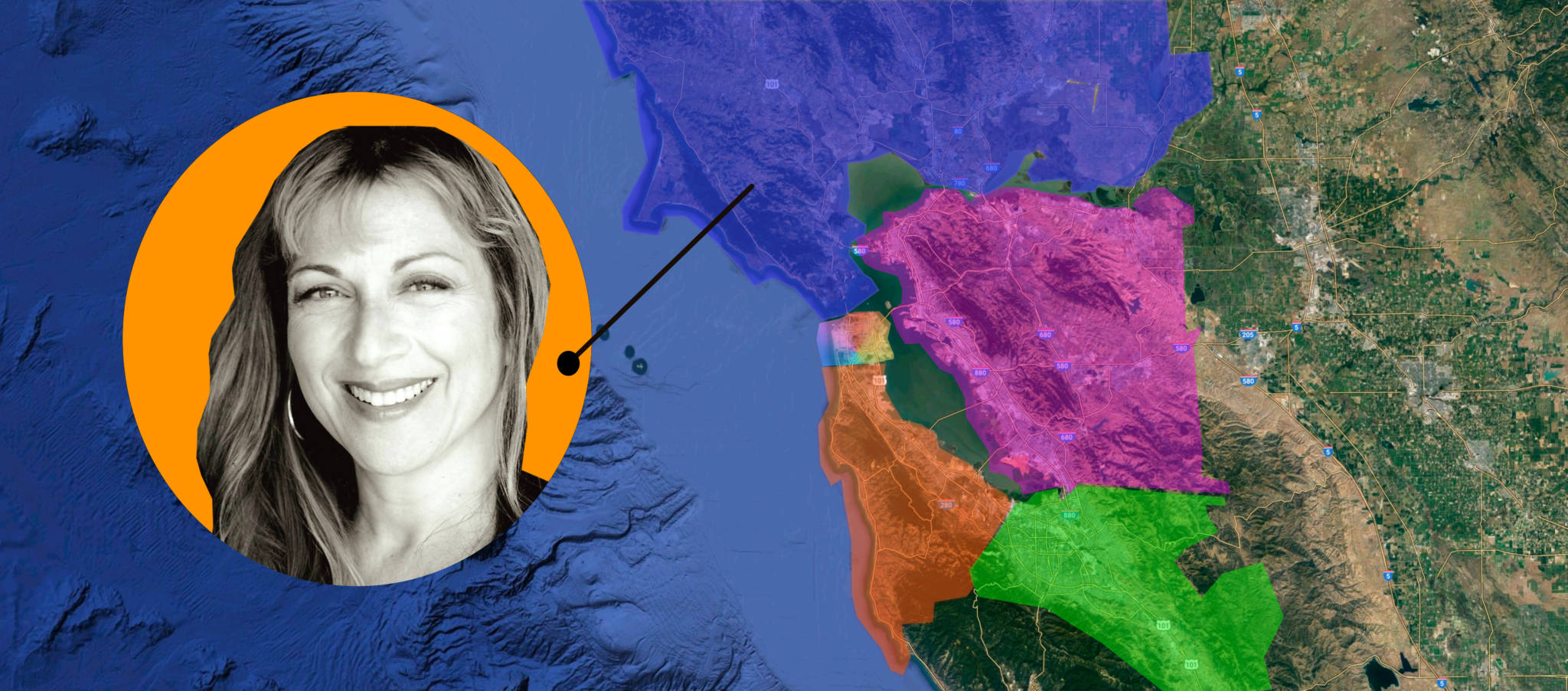

Beth Bich Nguyen, East Bay

When I was in high school, one of my closest friends was my boyfriend’s mother. We would talk for hours and hours, often about books. One day she gave me a copy of Love Medicine, Louise Erdrich’s first novel. I started reading and immediately fell in love with the gorgeous words, the landscapes, the characters who were stunningly complicated. They asked me to think more, think better, and reconsider everything I thought might be possible. I had grown up in a household of Vietnamese refugees in a very conservative part of Michigan — the same place Betsy DeVos is from—and I had gotten the message, early on, that my story didn’t matter. I’d pretty much only read literature by and about white people, and up to that point had read very little contemporary literature. All of this would change later in college, but in high school I was still thinking I had to fit in, which is to say disappear. Love Medicine helped show me otherwise. I wouldn’t have known to find Louise Erdrich, whose work is always a revelation, but I was lucky that I had someone in my life who knew that this was exactly what I needed to be reading. — B.B.N.

Beth (Bich Minh) Nguyen is the author of Stealing Buddha’s Dinner, Short Girls, and Pioneer Girl. She directs and teaches in the MFA in Writing Program at the University of San Francisco.

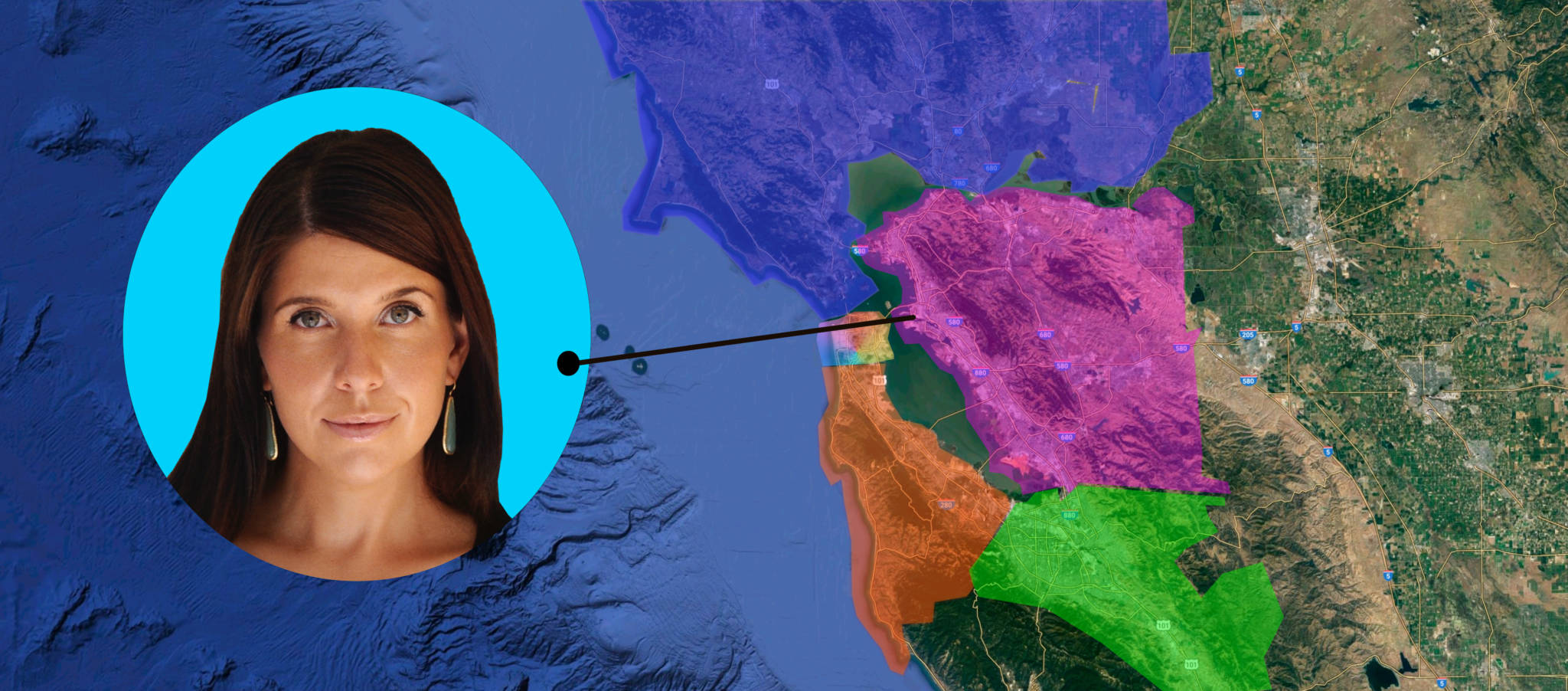

Molly Antopol, Oakland

I have admired Joan Silber’s work for years, for its warmth, humor, insight — and language that, line by line and paragraph by paragraph, inspires and surprises. Characterized by psychological precision and emotional generosity, her work has always felt to me that it belongs in the company of Grace Paley, Natalia Ginzburg, and Alice Munro. Her newest novel, Improvement, which effortlessly moves from New York to Turkey to Germany, brilliantly examines how even our smallest decisions can seismically affect the people around us. In poetically compressed, unshowy prose, Silber explores the lives of women I found myself caring about as intensely as the women in my own life. Improvement is an intensely soulful and beautiful book that I want to thrust into the hands of everyone I love. —M.A.

Molly Antopol is the author of The Unamericans.

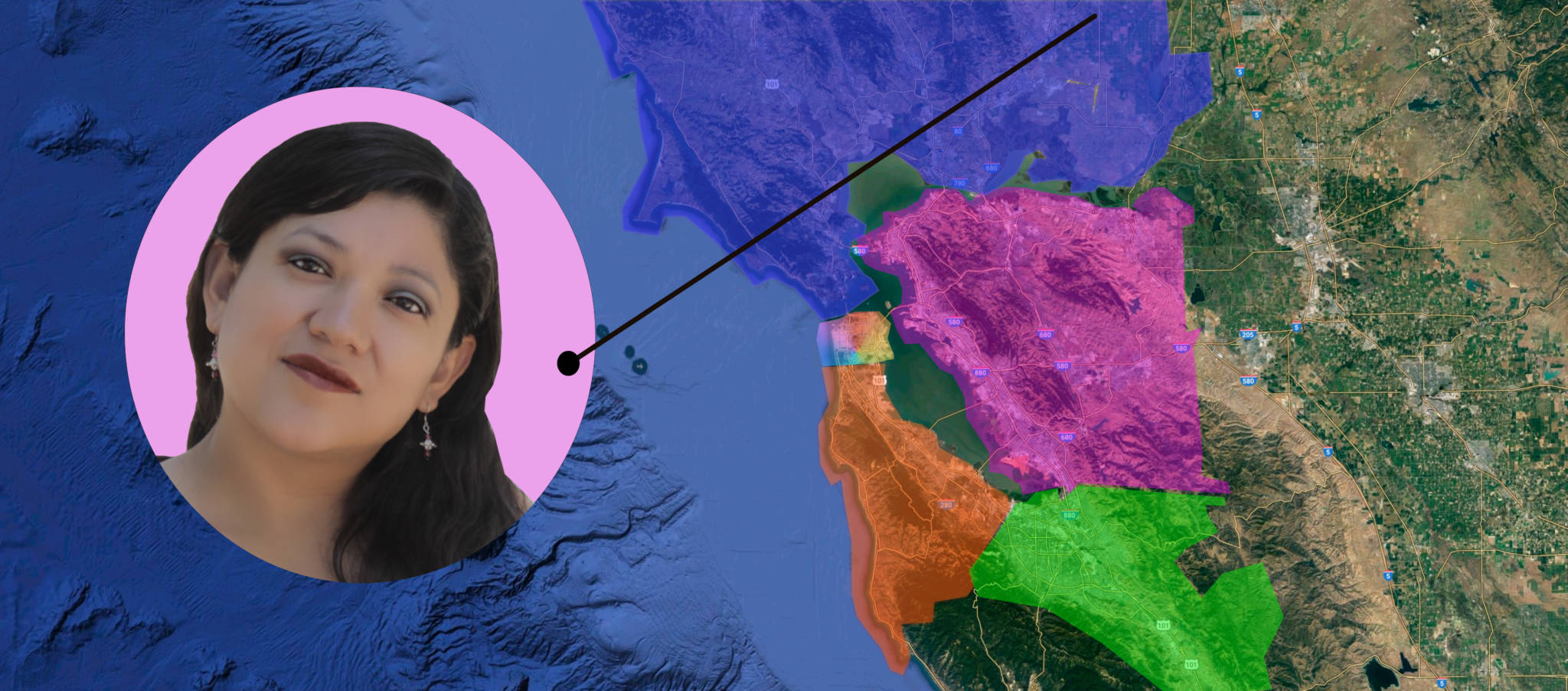

Reyna Grande, Woodland

I was 23 when I met my first author. The creative writing program at UCSC hosted Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston. I’d often felt I was clutching at a dream made of smoke, but seeing her onstage made my dream of being a writer feel more real. There she was, a flesh-and-blood author standing under the bright stage lights. At five feet tall she was as tiny as me, but she held herself with such confidence and spoke with such conviction that a minute into her talk, she was no longer small. She was larger than life, and I clung to her every word as she spoke about her memoir, Farewell to Manzanar.

Something changed for me that night. When I’d read her book, I’d felt connected to her through her words, but even more so at this moment when she was only a few feet away from me and we were in the same room breathing the same air. Though her book was about Japanese-Americans and the internment camps, I related to her story. As a woman of color and a Mexican immigrant, I knew how it felt to be marginalized, to have to prove constantly how American I was, always to have to fight for my right to remain. Her difficulties of trying to navigate American culture while trying to hold on to her Japanese heritage mirrored my own struggles.

Many of the students waiting in line to meet her were in tears, especially those of Japanese descent. They said to her, “Thank you for writing our story. You’ve inspired me to keep fighting.”

It was then that I fully grasped what a writer did. A writer changed lives and told her readers, You’re not alone. Have courage. At that moment, I became even more committed to my writing and empowering my own community. — R.G.

Reyna Grande is the author of A Distance Between Us.

Cristina Garcia, Marin

From the very first sentence of Autobiography of Red, you know that ordinary rules no longer apply. Geryon, the hapless hero, is a little red monster with wings who is sexually abused by his brother; struggles at school and against his diffident, chain-smoking mother; falls helplessly in love with a callow young man named Herakles; takes a serious interest in photography; and travels to South America where he attempts, among other endeavors, to dance tango in Buenos Aires. Part portrait of an artist as a little red monster, part a portrait of otherness, Carson collides Greek and indigenous Andean myths, high and low verbal pyrotechnics, and provides adventures aplenty.

With each re-reading, Autobiography of Red reminds me that heroism can come in the unlikeliest of packages. That art and artists exist in all places and times — and that they are necessary to understanding the world. That suspension of disbelief lies in the details and that humor can be both subversion and saving grace. And finally, that poetry can gift us with, to quote Carson here, “moments that are the opposite of blindness.” — C.G.

Cristina Garcia’s latest novel Here in Berlin is out now.

The Spine is a biweekly column. Catch us back here in two weeks.

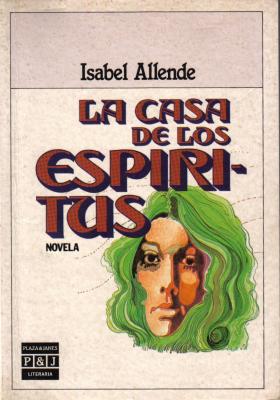

I stole it from my sister and read it in a hushed corner, turning page after page, like I was being spoken to in a trance. I’ll always think of The House of Spirits as a door, because Isabel Allende led me to discover other women writers. And each time I finished a book, the feeling was like walking into rooms that contained infinite rooms — for every writer had been touched and guided by another before her.

I stole it from my sister and read it in a hushed corner, turning page after page, like I was being spoken to in a trance. I’ll always think of The House of Spirits as a door, because Isabel Allende led me to discover other women writers. And each time I finished a book, the feeling was like walking into rooms that contained infinite rooms — for every writer had been touched and guided by another before her.