Suzanne Somers, I hereby declare that you’ve been fired. Hang up your Thigh Master and make way for the Queen. After five minutes of talking with underground comics legend Aline Kominsky-Crumb, I’m ready to buy any tonic, cream, pill, or supplement that could possibly account for her otherworldly effervescence. She’s stylish, bronze, and I’m confident she could body slam me. Her vigor feels impossible when I learn that she’s 70 years old.

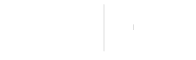

Then she tells me she had just finished chemotherapy three months before embarking on an international book tour to promote Love That Bunch, her career retrospective graphic novel, and I am floored.

“Getting through cancer, I got through it with no fear. I had no fear. And it wasn’t like I was trying not to be scared or I was trying to be positive. I actually wasn’t scared,” Kominsky-Crumb tells me. “At my age, I’m going to die from something.”

As I chat with her in a small Bernal Heights coffee shop, the vision of serenity and health before me seems light years away from “The Bunch” – Kominsky-Crumb’s tortured cartoon alter ego who figures prominently in Love That Bunch.

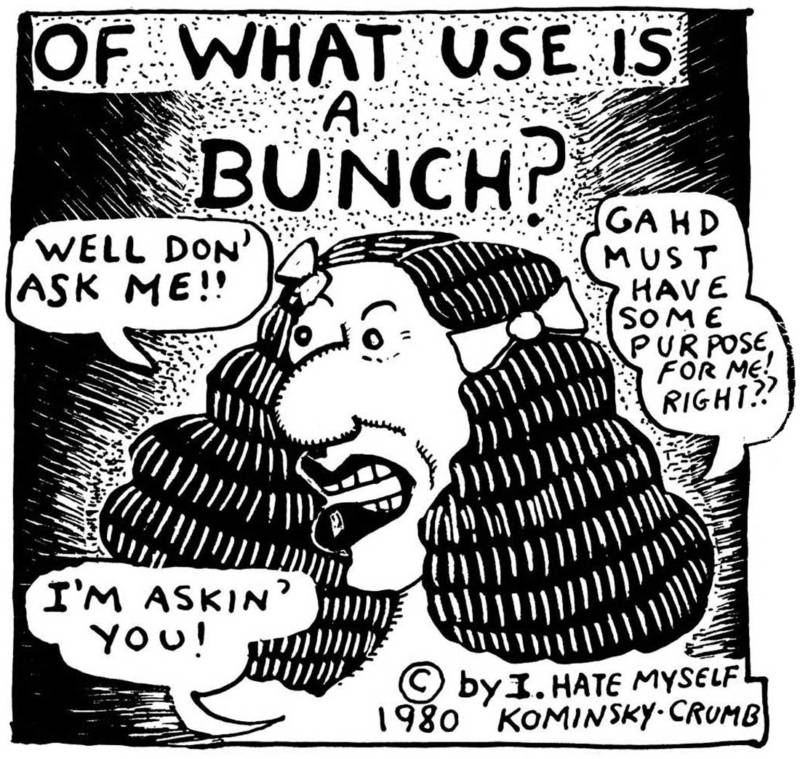

The Bunch was born during San Francisco’s ’60s underground comics scene, after Kominsky-Crumb fled a tumultuous upbringing in New Jersey. Rendered in her signature, appropriately uncontrolled style, The Bunch is raw, unfiltered, and living large in both carriage and personality. She’s also painfully vulnerable, obsessed with her appearance, and perpetually self-deprecating as she navigates the free love scene of ’60s California. While other women of the early underground comix movement drew themselves as gorgeous, strong superheroes, Kominsky-Crumb drew herself sitting on the toilet.

“[We were] all being feminists in our own way, but our vision of what that meant was different and contradictory in some cases,” Kominsky-Crumb says. “The original group were these militant feminists who I thought didn’t have much of a sense of humor, and they really didn’t like my work, particularly because it was self-deprecating.”

Kominsky-Crumb’s compulsion to draw confessional, funny, and unflattering work began as a response to a painful childhood. Her book opens with the story “The Young Bunch: A Nonromantic Unadventure Story.” It’s filled with disturbing scenes of early sexual encounters, and ends with a panel of father Arnie hammering her head against the wall for coming home late while mother “Blabette” frets in the background, “Arnie, don’t kill her!”

“A lot of it was just that raw anger and pain,” Kominsky-Crumb says, “and if you don’t express that, you go crazy.”

It has largely gone unacknowledged, but Kominsky-Crumb was the first woman to publish autobiographical comics. That’s all the more noteworthy considering that women are, traditionally, expert diarists; starting as young girls, writing on the inside cover of Hello Kitty journals, “WARNING: Keep Out. Snoops caught reading this will be cursed with 100 years of diarrhea and will burn in hell. This means YOU.” As girls get older, sometimes the stockpile of conflicted feelings grows too large, breaking tiny gold diary locks, and spilling into the public eye.

“You want to tell all of these bad things about yourself and then see if you’ll still be loved,” Kominsky-Crumb explains. “‘Look, I do this. Do you still love me?’”

Though both Kominsky-Crumb and her husband, cartoonist Robert Crumb, were always highly regarded within subversive art circles, they were afforded a relative degree of personal privacy due to their chosen medium. Comics were mostly either ignored or maligned up until the late ’90s, when academics got involved and deemed funny books “graphic novels.” Though Kominsky-Crumb herself is no wallflower, such anonymity was especially valuable to Robert.

“He has Asperger’s Syndrome. Very mild, but he does,” she says. “He had a very difficult time talking, but he would be in a corner drawing so he had a way to get it out and to communicate. If you’re really an artist, then you don’t have a choice. You’re one of the walking wounded.”

But then the release of Terry Zwigoff’s 1995 award-winning documentary Crumb jeopardized that blissful anonymity.

“Terry filmed it over the course of about seven years because he never had any money,” Kominsky-Crumb says. “We just sort of forgot about it. We let him do it because he was our really good friend. I thought if it ever got made at all, which I doubted, it would be some real small thing. In the film he asks me, ‘What if your mother see this?’ I said, ‘She’s not going to see this unless it comes to the mall next to her condo.’ And then it did. She was really upset.”

Luckily, Aline, Robert, and daughter Sophie had already moved to the French countryside when the movie was released. They had left rural Winters, Calif., where all of their neighbors worshipped God and guns, and bought a house in a small village in Southern France, where they still live today. Years of art, yoga, and therapy have resolved many of Kominsky-Crumb’s neuroses. Her brother, Sophie, and her grandchildren live next door. If there’s such a thing as a happy ending, Kominsky-Crumb may have found it.