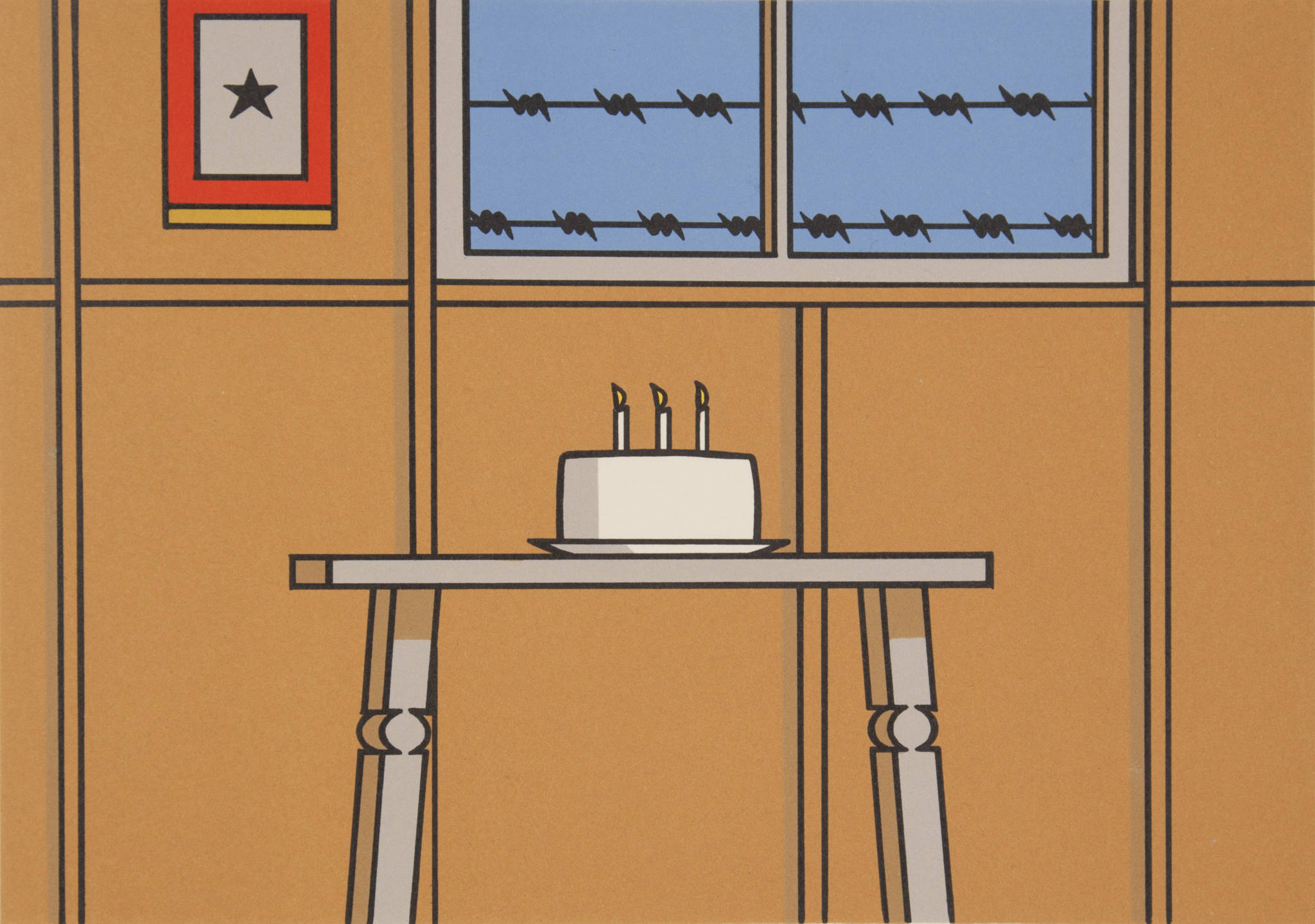

“Home.” “House.”

The terms are often used interchangeably, but a profound psychological divide separates the two. In an impressive multi-disciplinary installation, the artists featured in the San Jose Museum of Art’s exhibition The House Imaginary take up the heady emotional meaning of how and where we live.

In the aftermath of World War II, German philosopher Theodor W. Adorno wrote in Moralia Minima that the physical and psychological concept of home was forever altered: “Dwelling, in the proper sense, is now impossible.” Global catastrophe delivered death and displacement to millions. More than seven decades later, death and displacement due to war and economic privation still plague the world’s population, pitting aggressive nationalistic pride against our best impulses to care for one and all.

The House Imaginary does not directly address the current moment, but instead approaches topics including immigration, forced migration, and the effects of income inequality as they register in the Bay Area — from a more suggestive perspective.

Located in the first of three second-floor galleries that host the installation, Carman Lomas Garza’s 1997 color lithograph Sandia portrays a relatable, beautifully mundane scene: a multigenerational Latino family gathers on the front porch at dusk to eat watermelon. It is a scene that plays out all over the United States as spring gives way to summer, and warm evenings are tempered by the cool sweetness of the juicy melon. An accomplished image, and representative of Garza’s commitment to portraying Mexican-American life, Sandia is all the more poignant for the humane message it conveys: the family unit — however that is defined — is central to our understanding of home. That concept is realized by who we live with, as much as by where we live.