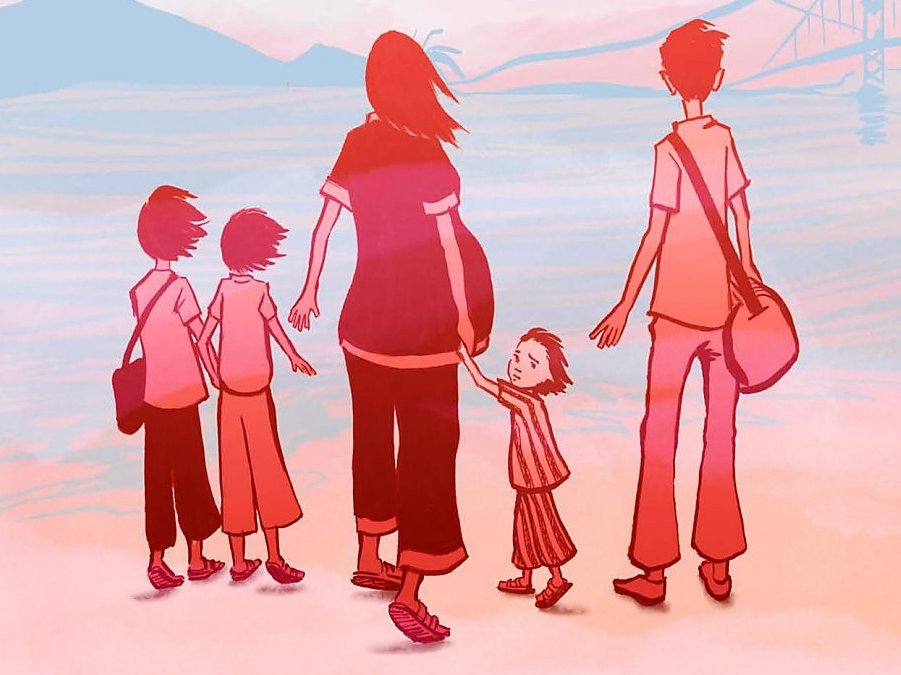

Cartoonist Thi Bui‘s Eisner Award-nominated graphic memoir is called The Best We Could Do; it’s the story of her family in the years before, during and after the Vietnam War. The Eisners — mainstream comics’ top award — are given out every year at San Diego Comic-Con, where Bui was one of this year’s featured guests.

Alone on stage for her spotlight panel at the convention, Bui invites audience members to come up and read passages from her novel. “There are several voices and I would like to not do them all,” she says. “I’m going to try to entertain you before I make you sad.” And her story is sad. Her parents lost nearly everything during the war, and ended up fleeing Vietnam in the late 1970s, when Bui was just a small child.

I meet up with Bui outside the San Diego Convention Center, as people in costumes rush to line up for more panels, and men ring bells on ice cream carts. She says the novel began with a grad school project. “I was a graduate student at NYU, deconstructing all of the bad representations of Vietnamese people in the Vietnam War in movies and pop culture and American scholarship, so it was a very academic grumpiness that I had at the beginning.”

Bui wanted to do more with that research, to make it accessible to a wider audience. And she says graphic memoirs — like Art Spiegelman’s Maus, about the Holocaust, and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, about growing up during Iran’s Islamic Revolution — inspired her. “I really wanted to do what they did,” she says, “weave the personal and the political and the historical to tell a story of the Vietnam War and all the things that caused it, in a way that I felt like I hadn’t seen before.”

“I’d heard a lot of the stories growing up, and the stories were pretty heavy … so I had this kind of heaviness that I grew up with, and I wanted to make sense of the stories.” — Thi Bui

So Bui interviewed the closest sources she had — her parents. She says telling them she was writing a book about their lives helped break the ice. “It’s really hard to sit your parents down and say ‘Tell me all about your painful history,’ but if you tell them, ‘I’m working on a book, could you help me with my school project,’ then they’ll oblige … your oblique Asian strategies!”

The book delves as much into her family’s history as it does Vietnam’s; traumatic things her parents had seen as children and young adults in the years before and during the war. Bui says she asked basic questions to get the connective tissue of her parents’ stories: “Was it hot, were you hungry, how did the sand feel on your feet after you lost your slippers in the boat?” These questions helped her parents recall rich details that Bui wove into the graphic novel. Details like the executions of political prisoners her father witnessed, how much money her mother got for selling her valuables, the dimensions of the boat her family took to flee Vietnam.

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))