Multimedia artist Lava Thomas‘ practice centers on social justice, female subjectivity and shifts in historical discourse over time. Her latest work, Mugshot Portraits: Women of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, celebrates a group of women whose vital contributions to the 1955-56 Montgomery Bus Boycott have been subsumed by a historical narrative that centers on the accomplishments of men associated with the modern civil rights movement.

The Rena Bransten Gallery installation of this work could be described as “slow.” It’s a sense first reinforced in presentation; Thomas’ twelve larger-than-life graphite and conte pencil portraits are installed in the front gallery with generous distance between them, which encourages viewers to spend time with each rather than rushing between images before their full measure is appreciated.

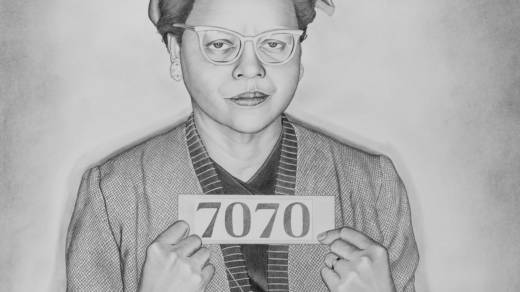

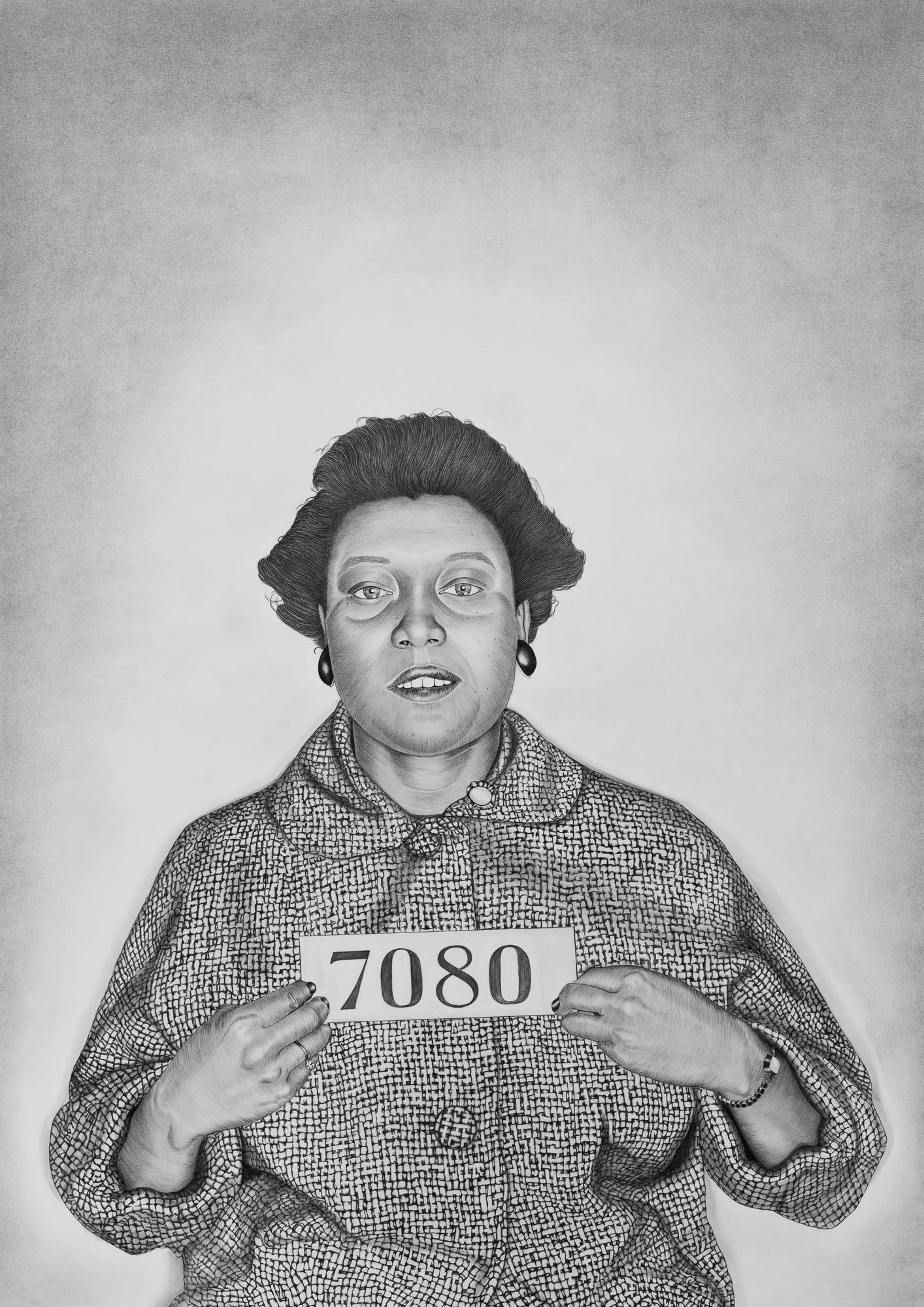

More importantly, the portraits reveal their splendor slowly. Fine lines demarcating a defiant flash in the eyes, or the delicate threshold that marks the upper lip, or the fabric of a winter coat attest to the time and attention Thomas gave to each portrait. Thomas portrays each sitter—well known Rosa Parks, but others who fell out of the historical record—with slight halos, honoring them as work-a-day saints who, in February 1956, turned themselves in to the Montgomery Police Department for their role in organizing the bus boycott.

Though confined to a nuanced black-gray-white spectrum, vibrance as hot as an Alabama summer day beams from each portrait. In the gallery’s anterior space, tambourines fitted with alternating opaque and mirror surfaces remind us that these women’s contributions, like the tambourine to an ensemble band, are small but powerful.

Thomas’ project incorporates crucial critical topics—the Black body as object, not subject, and how that status is determined photographically—that bear historical and contemporaneous significance. Mugshot Portraits calls up an execrable 19th-century photographic project commissioned by the Swiss-American naturalist Louis Agassiz (1807–1873). Enslaved Africans were brought from regional plantations to J.T. Zealy’s Columbia, South Carolina studio and photographed half nude and from different angles. Treating photography as a “factual” tool, Agassiz interpreted these combinations of portrait and scientific illustration through the lens of physiognomy, falsely deducing that Africans are genetically different—and inferior—to their European counterparts. Thomas’ subjects descended from the women, and men, who sat vulnerable before Zealy’s camera. Like their forebears, they carry the burden of racism’s violent gaze. Unflinching, they look back without shame, defying us to acknowledge our complicity in their condition.

Thomas labored over each image, absorbing and translating them graphically, in enormous contrast to the police photographer’s quick deployment of the camera shutter. That difference in purpose—between Thomas’ work and the unknown police photographer—is striking. The photographer (very likely a white man) captured the likenesses of these sitters for record-keeping purposes. Thomas honors them. In mugshots, subjects come to us as numbered, nameless elements in a penal system structured to dehumanize those caught in it. A body represented in mugshots defies state definitions of “law-abiding” (further abject because these sitters are both Black and female), inhabiting what theorist Allan Sekula (1951–2013) calls “a shadow archive” that mirrors the social construct that produced it.