The genius of the plays of Young Jean Lee is that no matter what your personal opinion of a specific work is, it’s impossible to view one with indifference. It’s a rare playwright who can consider charged topics such as race (The Shipment), gender privilege (Straight White Men), and gender identity (Untitled Feminist Show) and reveal them as fully nuanced topics with fully nuanced humans on either side of their inevitable ideological divide. A line or scene that may have one audience member nodding along in recognition may provoke a recoil of shock in another, but whatever their reaction, neither will walk away without a strong opinion of the experience.

Lee’s public meditation on Christian faith, CHURCH—currently produced by Crowded Fire, and directed by Mina Morita—is a brief slip of a play, clocking in at around 60 minutes. In concept, it portrays a much-abbreviated church service, one that’s over long before the congregation-audience can begin wriggling uncomfortably in their seats or looking longingly at the exits. The basic elements of a Sunday morning churchgoing—liturgical music, earnest sermonizing, a call to prayer—form the foundation of the performance, and it’s clearly a structure familiar to many audience members, with several spontaneously murmuring amen and offering grace at the appropriate times.

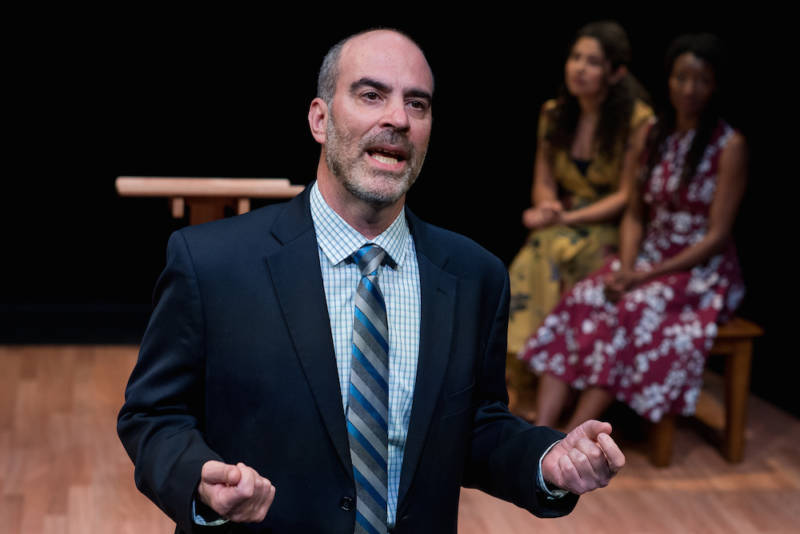

Even for a staunch atheist with religion an integral but maddening part of the long-distant past, a condition I share with the playwright, there are moments in CHURCH that resonate on a personal level. The opening monologue, performed in the dark by Reverend José (Lawrence Radecker), is a pointed observation of the all-too human condition of self-importance and half-hearted armchair activism, directed seemingly specifically to the skeptics.

“You claim to care about suffering in the world and take luxurious pleasure in raging against the perpetrators of that suffering,” he admonishes. “But this masturbation-rage helps nothing and no one.” I doubt I’m the only non-believer in the room who feels personally singled out by this merciless deconstruction of the well-intentioned path to hell. And I can’t deny that it’s a scripture I can subscribe to, right up until the moment he concludes with: “The day will come in which the Lord God Almighty comes in a shining blaze of glory, and the knowledge of your shallow heart will cause you to bite through your own tongue with grief,” and in a single sentence everything I might otherwise have agreed with is subverted by holy fear-mongering. It’s a subversion not at all uncommon in Lee’s confrontational aesthetic.

Other moments in the play appear tailored to resonate more with the true believers in the room, as a cluster of three female reverends join Radecker onstage, clad in playful floral prints (designed by Alice Ruiz), and offering the assembled congregation heartfelt smiles of welcome, as they take turns at the modest podium set centerstage. The Reverend Jordan (Jordan María Don) invites the audience to offer up prayer requests. The Reverend Nkechi (Nkechi Emeruwa) quotes from Hebrews as the audience murmurs along.