One of the most iconic burns in the history of The Simpsons occurs in the episode “Two Dozen and One Greyhounds.” In the wake of a botched dinner party, Rev. Lovejoy storms out of the Simpsons’ dining room and yells, “See you in hell!” before slamming the door. Taking a beat, he re-opens it to smugly add “from heaven”—and slams it again.

In artist Craig Calderwood‘s hands, that line, which titles their latest show at the Luggage Store Gallery, is less of a reference to the sitcom and more of a riff on the catty, religious certainty that shades Lovejoy’s clapback. As a phrase, “see you in hell, from heaven” packs a linguistic wallop, a zinger of immeasurable sass that is literally cosmic in scope. But even if you divorce the remark from its holier-than-thou connotations, you are still left with a taste of the world’s oldest binary thinking—the good go up, the bad go down, and I know exactly where you stand.

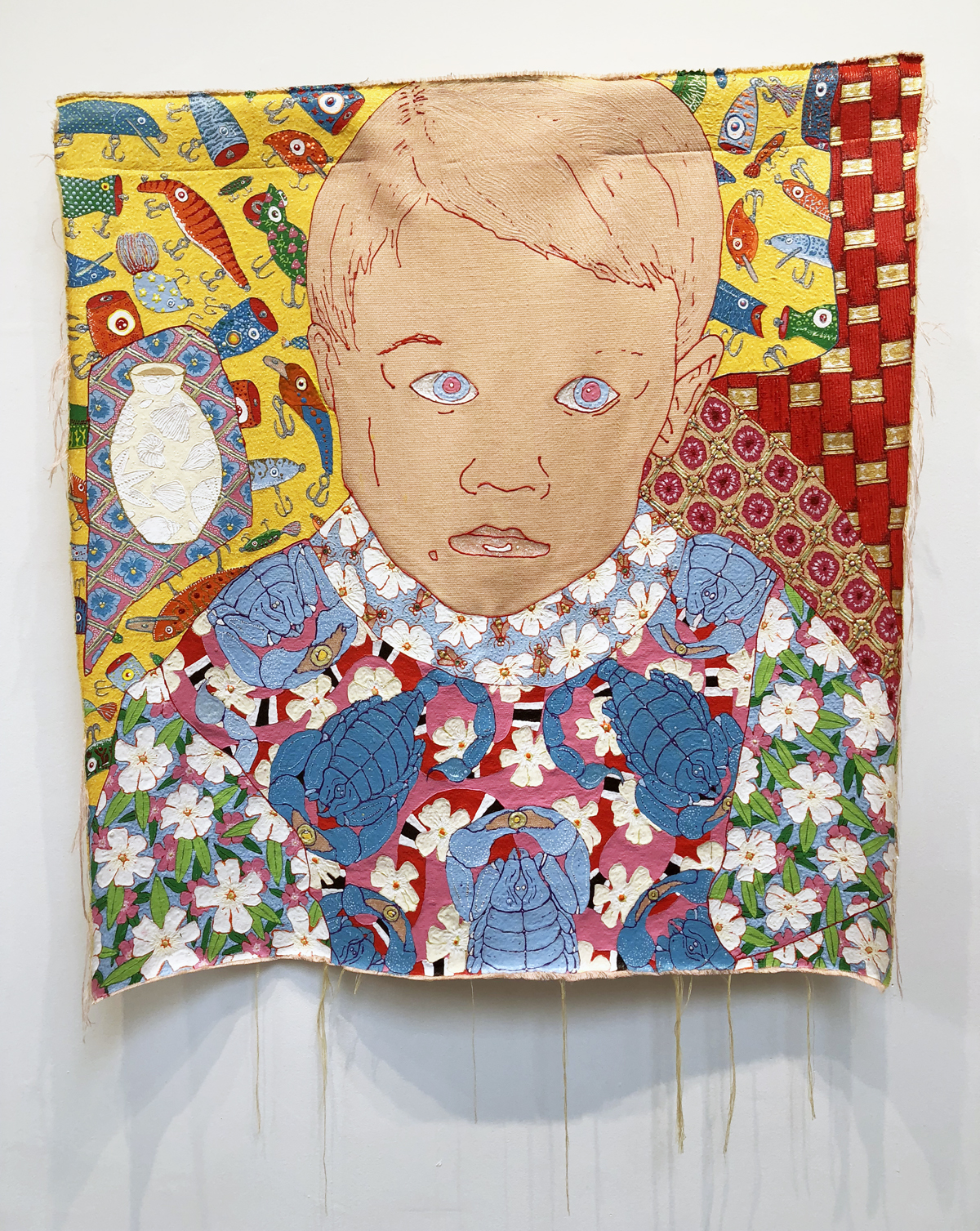

It’s a kind of mindset that Calderwood has little use for, one that is far too convenient to actually express the complexities and contradictions that are part and parcel of being a person, especially a queer person. Calderwood’s work thrives on complications. In keeping with queer art traditions from Warhol to Caravaggio, Calderwood takes on the static meaning in everyday symbols and expands them light-years beyond their dictionary definitions. Throughout their show, Calderwood (who uses she/her and they/them pronouns) embeds one loaded image after another to create portraits that are unified by style, but alive with tensions.

Calderwood’s drive to complicate manifests itself on the most basic level, in the raw material of their work. The show was originally conceived as an exploration of humbler art techniques, and for See You in Hell Calderwood returned to the craft supplies from the bible camp they attended as a child. Working with these media is a technical challenge that Calderwood nails to impressive effect. Wielding dimensional paint and polymer clay to create impossibly detailed paintings and brittle but fleshy sculptures, there is not a single piece within their show that looks remotely gimmicky.

But Calderwood’s materials complicate on a conceptual level too. “[They were materials] that I used to help me socialize,” Calderwood says, “I would make objects for people [at camp] to express desire in safe ways.”