In response to the imposing and extractive Land Art of the 1960s and 1970s, artist Judy Chicago once said: “I was and am horrified by the masculine built environment and the masculine gesture of knocking down trees and digging holes in the earth.”

Chicago’s reaction to this kind of art was to create work like Women and Smoke (1971–72), a film piece in which she and other women painted their naked bodies in iridescent colors, set off smoky flares, and danced fervently in a desert landscape. The work has a primordial feel; this isn’t the world of Richard Serra or Michael Heizer where large-scale landscapes are dug up and reconstructed. Chicago and her collaborators left no marks on the land; once the colored smoke dissipated, the only remnants were documentation of their relationship with it.

But the story of work like Chicago’s begins at least six decades earlier when, in 1905, the Oakland-based photographer Anne Brigman began creating nude self-portraits in the mountains. Though this act might be unremarkable today, Brigman is considered the first woman to photograph herself nude—or at least the first to publicize it. The work that followed is the foundation of Anne Brigman: A Visionary in Modern Photography, a major retrospective at the Nevada Museum of Art in Reno.

Following the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, Brigman began making more regular trips to the Sierra Nevada to escape the dire situation in the city. Here too Brigman was ahead of her time; it was then rare for women to hike the high Sierra, which required long stagecoach rides and pack mules. Brigman’s legacy was born when she united her burgeoning interest in female nudes (not always her own) with her love for nature and the Sierra.

Brigman practiced a form of photography called pictorialism, which drew on the aesthetics of painting in order to distinguish fine art photography from more scientific photography. Brigman’s work also evidences a clear inspiration from classical Greek and pre-Christian art and mythology. One of her earliest nudes in the Sierra is Dryads (c. 1905), depicting a large, twisting juniper tree clinging to a granite rock face. Two women lounge on the granite surface, one above the other, looking at each other as if in the middle of leisurely conversation. The title refers to the tree nymphs of Greek mythology; and even absent the presence of water, the models’ poses recall the countless bathing nymphs littered throughout art history.

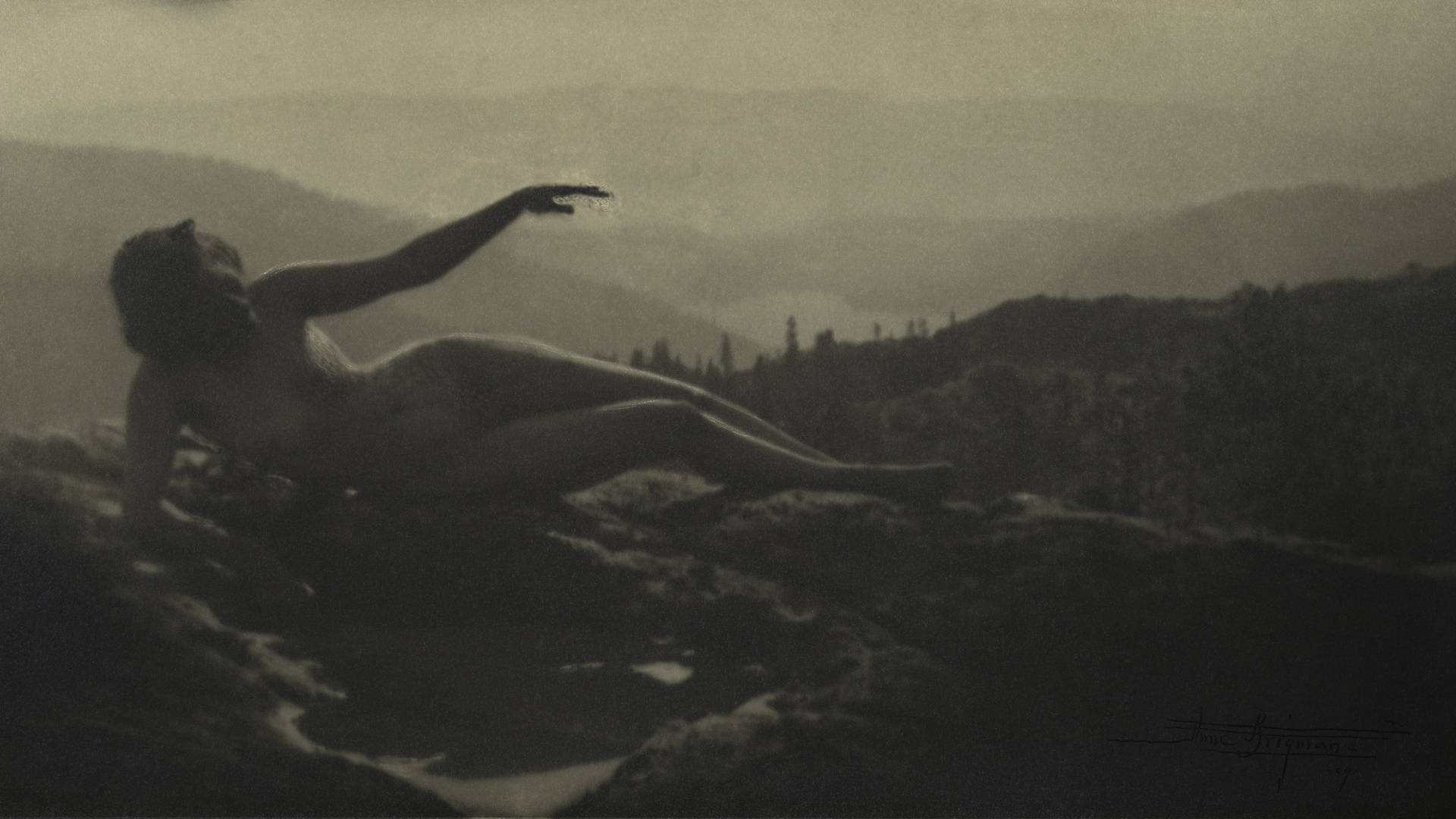

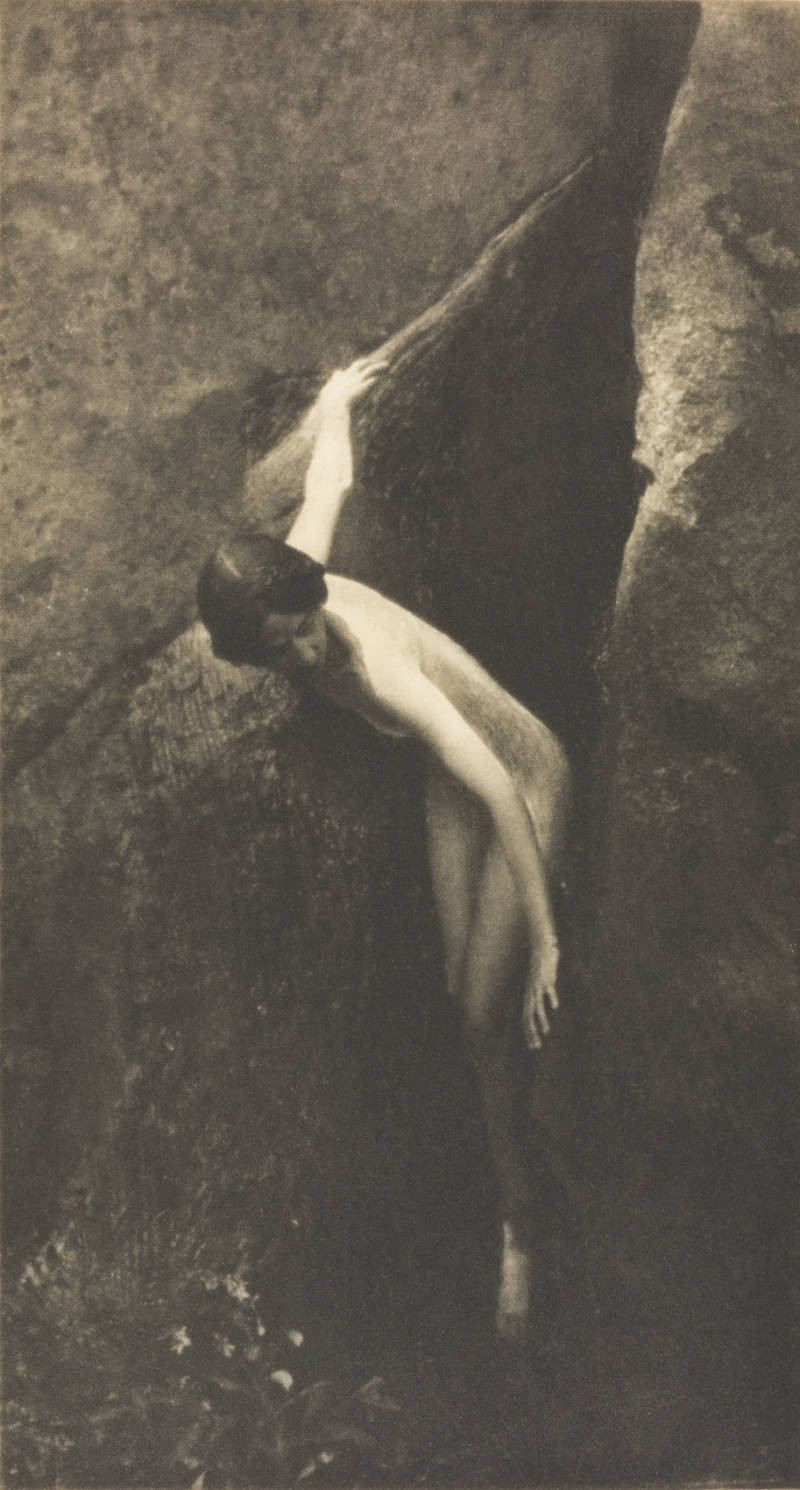

Beyond the classical allusions, Brigman’s work exhibits a profound connection with nature—especially with trees. In Soul of the Blasted Pine (1906), one of the best representations of this relationship, a subject stands inside the crevice of a tree trunk that has been felled, presumably, by a strike of lightning. The woman grips the trunk with one hand and stretches the other towards the sky, as if to recreate the tree’s former state. The distinction between the forms of the woman and tree is blurred, and of her work, Brigman said, “I’ve dreamed of and loved to work with the human figure—to embody it in rocks and trees, to make it part of the elements, not apart from them.” Her work was a way of erasing the artificial divide between individuals and their landscapes, between human and non-human natural elements.

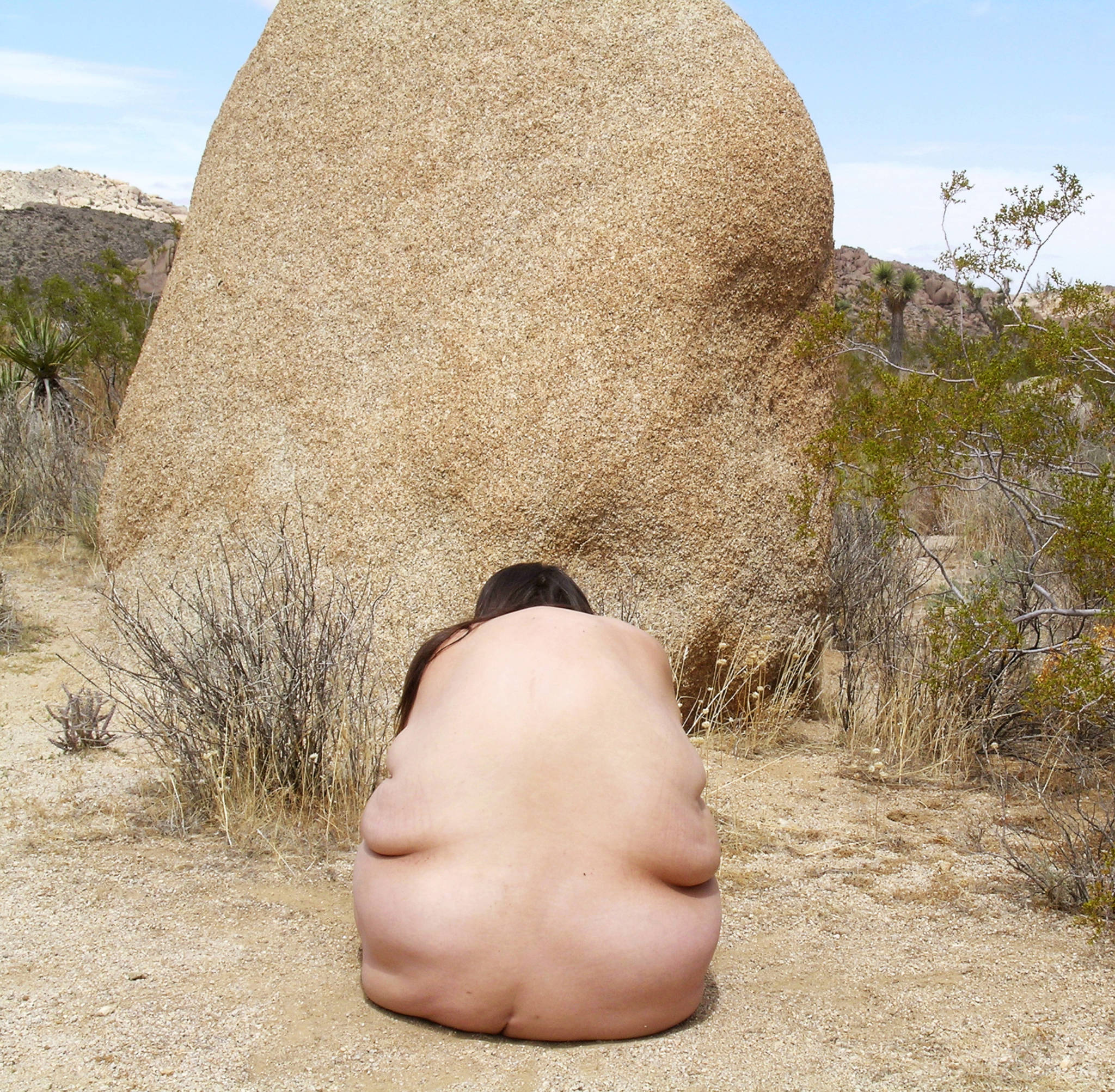

This erasure is seen in many of Brigman’s Sierra works, such as The Lone Pine (c. 1908), which depicts a wind-ravaged pine growing practically horizontally out of a granite surface. A model kneels on the boulders in front of the tree with a curved back and her head buried in her arms. She replicates the curvature of the pine, lending it some of her humanity while also borrowing some of the tree’s timelessness. This paganistic relationship with nature was also about freedom—the freedom to be in the land and to create. “My pictures,” Brigman wrote in the San Francisco Call newspaper following her separation from her husband, “tell of my freedom of soul.”