There’s a long-standing narrative trope in theater, film and books of an uptight Westerner “finding themselves” using the backdrop of an unfamiliar land as a way to frame the action, and lend it an air of exoticism. In Everything is Illuminated, directed at the Aurora Theatre by outgoing Artistic Director Tom Ross, this trope is central, as New York writer Jonathan (Jeremy Khan) travels to the Ukraine to find the literal land from which his Jewish family roots stem.

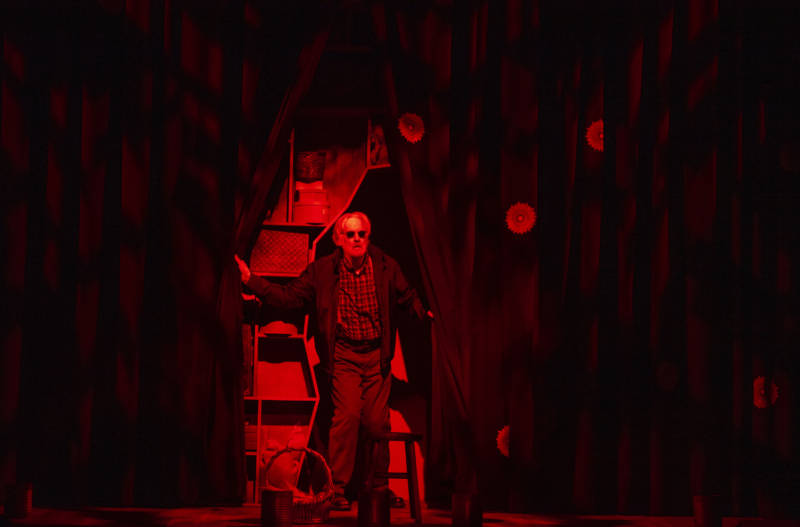

Armed only with an old photograph and a surfeit of foolish hope, Jonathan looks for the woman who saved his grandfather’s life during World War II. This quest makes little objective sense to Jonathan’s so-called guides: the upbeat America-phile Alex (Adam Burch) and his ill-tempered Grandfather (Julian López-Morillas). But they’ve been paid upfront for the excursion, so after some pushback from Grandfather (the driver, despite his affectation of blindness), the three plus the flatulent “seeing-eye bitch” named Sammy Davis Jr. Jr. set off on a stereotype-laden, buddy-flick-worthy roadtrip to find the village of Trachimbrod, Jonathan’s grandfather’s hometown.

For every scene that paints Jonathan as an ugly American, whining about the local cuisine or spartan accommodations, the play isn’t hesitant to paint a similarly unsympathetic portrait of Grandfather, whose anti-American, anti-semitic tirades go mostly untranslated by his affable grandson. Alex only wants to keep the peace, and manufacture an experience for Jonathan that will satisfy him enough to recommend the business to others when he goes back to America.

“This is your journey,” he keeps reminding Jonathan with a toothy grin. Unfortunately, for much of the first half of the play, the script is so frequently wooden and transparently cinematic in intention—if not delivery—that it’s hard to feel invested in the expedition, despite strong performances from the actors.

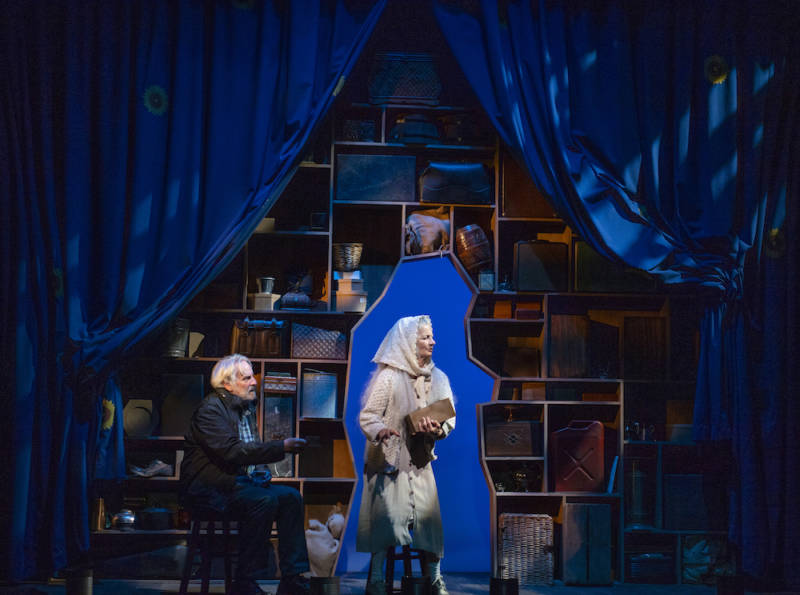

Block (and, I imagine, Foer, though I have yet to read the book) forces Alex to speak in his broken English even when he is acting as narrator, not speaking directly to Jonathan, and the inevitable laughs his imperfect command of the language inspires feel patronizing. Also derailing the play’s momentum is an abrupt shift to the far past, to introduce characters from Jonathan’s novel-in-progress: mythologized versions of his ancestors (played by López-Morillas and Marissa Keltie) who speak in exaggerated borscht-belt patois and urge him to keep writing, as neither he nor they know yet where they will wind up.

That said, when the road-trippers at last make contact with someone outside of their insular bubble of machismo and neurosis, the play turns the previous set of tropes on their heads, revealing what had been clumsily alluded to all along: that there’s far more beneath the surface of any one “journey” than any one protagonist will ever know.