In 1991, rock critic Gina Arnold stood under the 115-degree Arizona sun at a stop of the pioneering touring festival, Lollapalooza. The event was in its first year; Nine Inch Nails, Siouxsie & the Banshees and Ice-T headlined; tickets were $27; and the organizers had “this hippyish belief in music to elevate people,” Arnold recalls.

Twenty-seven years later, music festivals have swelled into a big business. Save for a few exceptions, two companies run the show: Goldenvoice—whose repertoire includes Coachella, Stagecoach and Firefly—and Live Nation, which produces Bonnaroo, Austin City Limits, Sasquatch! and dozens of other fests around the country. Attendance costs have ballooned to several hundreds of dollars and that hippie spirit has given way to corporatization.

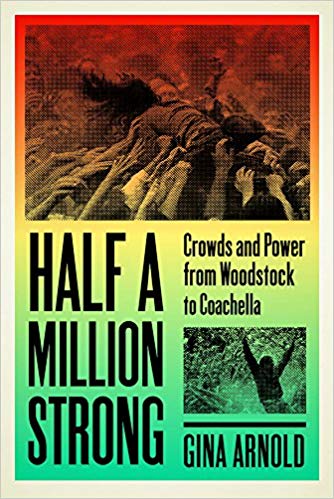

Arnold, who once wrote for Rolling Stone, Spin and East Bay Express, and now teaches at the University of San Francisco, studies the communal power and changing nature of the rock festival in her new book, Half a Million Strong: Crowds and Power from Woodstock to Coachella.

A comprehensive history of every American rock festival would be too unwieldy, so Arnold gave herself strict parameters: the events in question couldn’t take place in stadiums and had to draw over 400,000 people in attendance. With these guidelines, Arnold maps out a social history of music festivals in the United States.

The rock festival, she argues, sells a promise of utopia. For one weekend, attendees can enjoy a respite from the individualistic, isolating culture of capitalism and the work week’s grind. But more often than not, the promise is doomed from the start.

“We go to the rock festival with these high ideals,” Arnold says. “It holds out to us things that we really want in life: community and a sense of connection. But when you get there, it’s actually a harsh environment with a lot of crowds, noise and distress. … Sometimes, it extends to much worse things, especially if you’re a non-male, non-white person. What does it mean if our idea of utopia isn’t enjoyable for non-white, [non]-males?”

With large-scale festivals, this utopia-for-sale is mostly accessible to the privileged among us. To attend the “best weekend of the summer,” as Los Angeles’ FYF Fest sells it, attendees shell out hundreds for admission, travel and Instagram-worthy outfits. Once there, a “no ins or outs” policy forces the purchase of beer, food and other wares at high markups. The respite is there—depending on your tax bracket.

In Half a Million Strong, Arnold highlights the tension between festivals’ utopian aims and the quest for profit. She examines how heavyweights of the 1960s, like Woodstock, Altamont and the Monterey International Pop Festival, laid the idealistic foundation for the modern-day music festival. Raves get a chapter as the natural extension of those ’60s fests, but Arnold looks at how the capitalistic aims of promoters complicate their ambitions of peace, love, unity and respect.

While examining these tensions, Arnold also looks to lesser-known events that have uplifted marginalized communities and advocated for social good. Wattstax festival in Los Angeles in 1972, a benefit put on by Stax records on the seventh anniversary of the 1965 Watts riots, offers an example of a festival that—boasting a bill of Isaac Hayes, the Staples Singers, Richard Pryor and Carla Thomas—carved out a refuge for and by black folks.

That human need for a sense of community, Arnold explains, is why festivals are in more demand today than ever. “There’s just a real emptiness in people’s experiences now,” Arnold says of the increasingly private and isolating experience of our technology-driven society. “People just have a huge hunger for what I called in the book ‘listening together’—that sense of being a part of something larger.”