When I first read the title of Harvey Quaytman’s exhibition at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, I assumed the “static” of Against the Static was, because it followed an article, the noun form of the word: the buzz and crackle of signal disturbances.

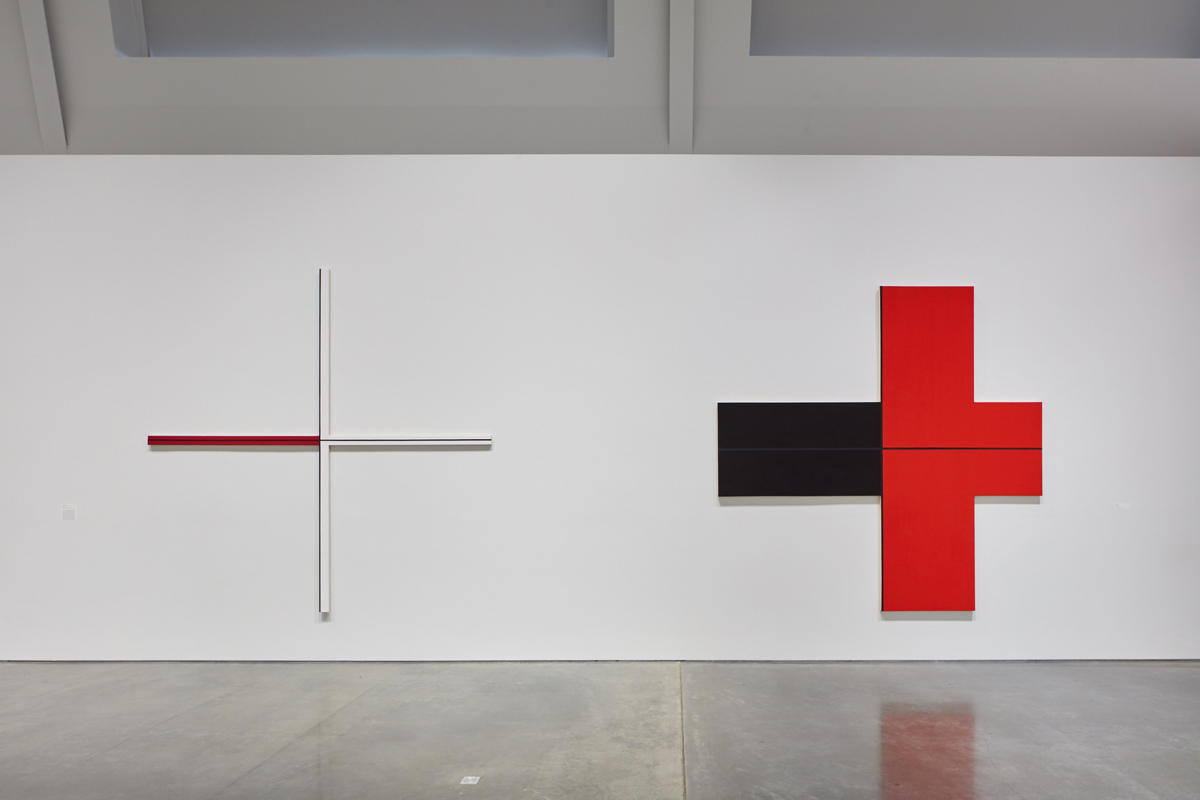

Halfway through the late artist’s first museum retrospective, I realized I had it all wrong. Quaytman’s practice was about movement, curves and the (very) active process of making a painting in his own alchemical way. The “static” he rallied against in his four-decade long career as part of the downtown New York art scene was an adjective: the unmoving, still and sedentary descriptor.

But then again, Quaytman loved language. In addition to wood, stretched canvas, acrylic paint, rare pigments and various chemical compounds, language was one of his materials. The titles of the paintings in Against the Static are filled with delightful puns, alliterations and half-rhymes. In that spirit, my initial confusion feels intentional and altogether appropriate.

And so a third understanding of the exhibition title opens up: Quaytman, under-recognized but incredibly prolific, painted against the static that was the noise of fads, movements, successes and failures in the 20th-century art world. The result is a body of work that patiently lumbers along its own trajectory, and an exhibition that reveals surprisingly fresh canvases around each corner.

Friends, colleagues, admirers and even museum directors use phrases like “artist’s artist” and “painter’s painter” to describe Quaytman. (This is code for “he didn’t sell a lot of work,” “he didn’t get the critical attention we think he deserved,” or both.) But these characterizations also make it sound like you have be an artist, or specifically a painter to appreciate Quaytman’s work. BAMPFA curator Apsara DiQuinzio organizes and annotates the exhibition to prove this is definitely not the case.

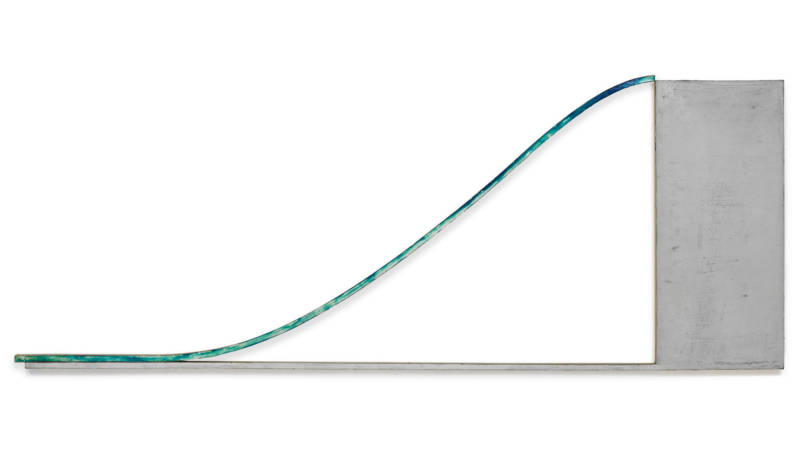

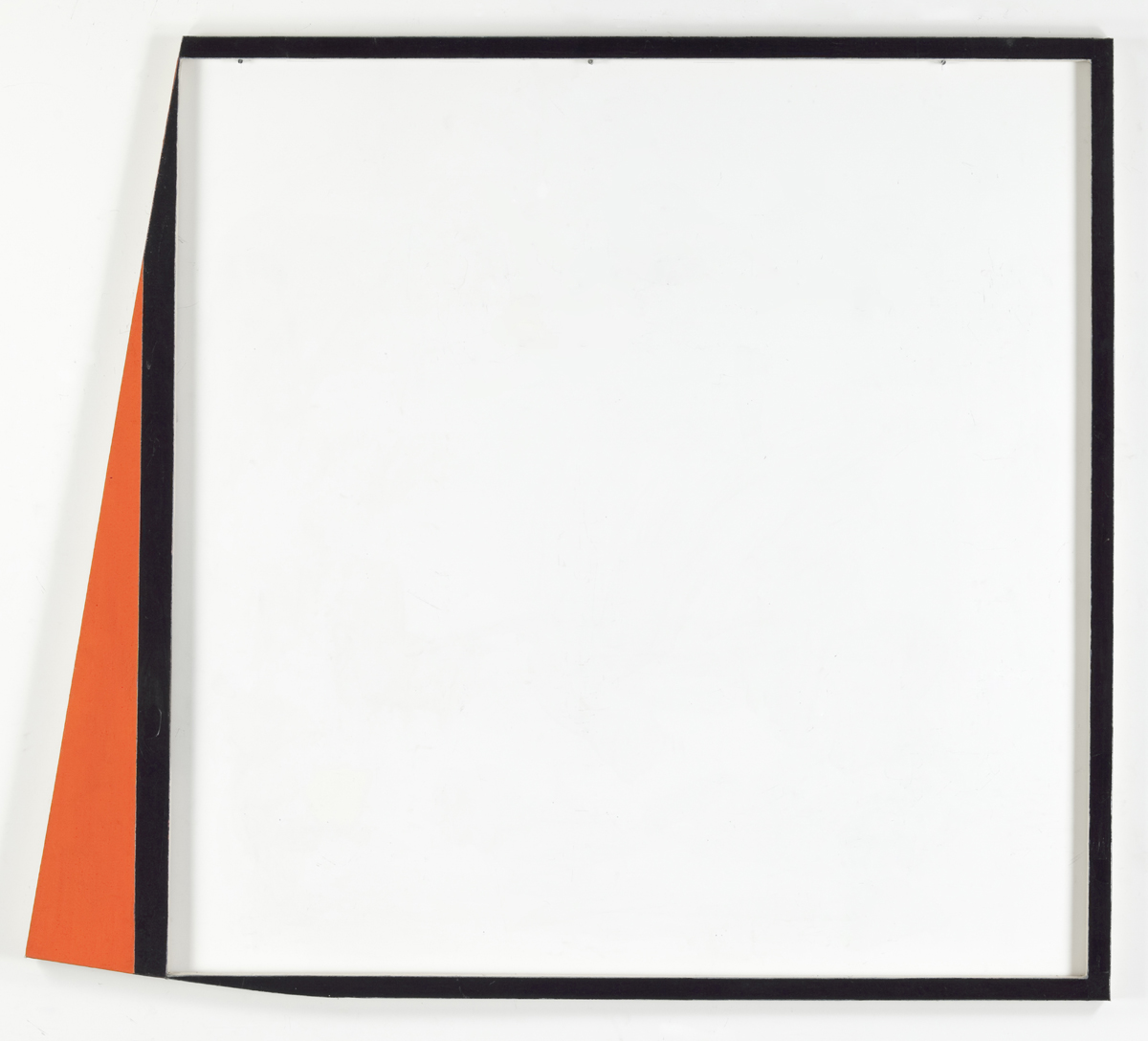

Quaytman’s career began in the early 1960s, heavily influenced by the colors and sinuous curves of abstract expressionists Arshile Gorky and Willem de Kooning. His rectangular canvases covered in swirls quickly turned into enormous curvilinear shapes inspired by Hebrew letters, Islamic calligraphy, airplane wings and the swing of a plumb bob. Pulling these paintings into object-hood even more, Quaytman poured acrylic resin medium directly onto the canvas surfaces, damming up the edges with aluminum tape and leaving behind crispy ridges.