Walt Whitman’s poem “To a Stranger” is an ode to an outline, a poem addressed to an imaginary other that is so vivid in the mind’s eye one forgets they’re a dream. His work is a masterpiece of longing, a lifetime of shared intimacy mapped across a fleeting look.

But one wonders what shape “Stranger” would have taken if Whitman, a gay man, had a language to describe his love in both poetic and political terms. If he had lived into the 21st century and had the means of expression we possess today, would he have written from such a melancholy distance? If he had witnessed all of the ways queer love can be lost—to AIDS, drugs, violence, neglect—would he risk hurt to embrace the world?

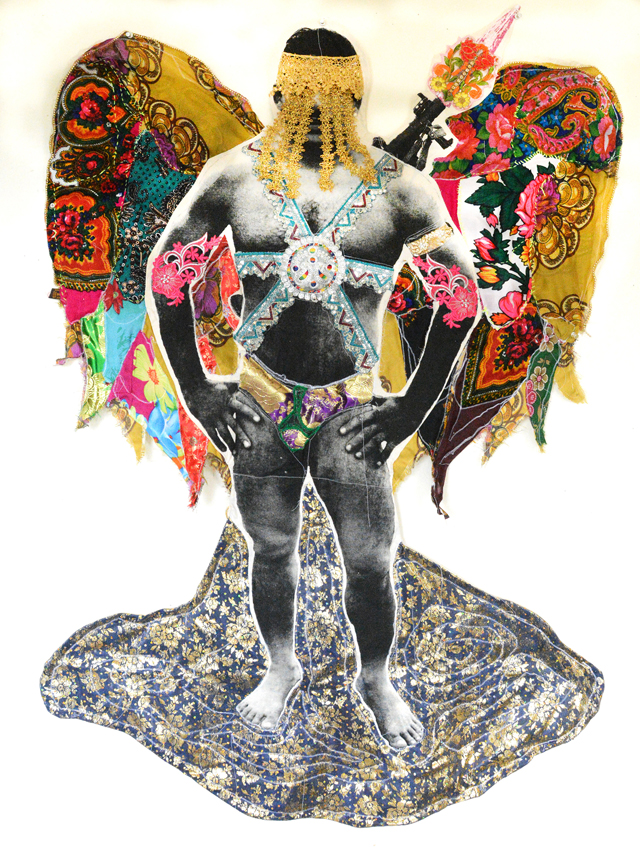

Taking its title from the final verse of “To a Stranger,” SF Camerawork’s I am to see to it that I do not lose you finds Orestes Gonzalez and Zulfikar Ali Bhutto taking on Whitman’s spirit, while honoring and recognizing great loss. The imagined others they pine for aren’t romantic partners, but fellow queers who have fallen and been forgotten, whose presences are dearly missed and whose voices yearn to be heard. [Ed. note: This show is curated by frequent KQED Arts contributor Roula Seikaly.]

It’s a show concerned with queer time—how one accounts for the present without a clear line to the past, how one builds a future from a murky and muddled now. And while I am to see can sometimes want too much, it remains a remarkable showcase of two artists holding out their arms to shepherd their subjects from the fringes back into the fabric of history.

Of the two bodies of work on display, Orestes Gonzalez’s narrative photo series Julio’s House most fully engages with the spirit of Whitman’s abstract longing. Documenting his late uncle’s home in the wake of his passing, Gonzalez creates an intimate portrait through the possessions of a man who is no longer there.