Vija Celmins’ lessons on how to be an artist, based on her own 80 years of life experience, might look something like this:

- Reduce your practice to its most simple elements: looking and making.

- Do it over and over and over again.

Of course there’s more to it than that, and over the past 57 years (if we begin her career in 1962, her first year in graduate school at UCLA), Celmins has proved that an incredible variety of work—oil paintings, graphite drawings, cast and painted objects, charcoal drawings and prints—depicting an incredible variety of things—stars, waves, spiderwebs, clouds, studio objects, airplanes, the desert floor—can emerge from that deceptively simple premise.

To Fix the Image in Memory, SFMOMA’s retrospective of the Riga-born, New York-based artist (her first in North America in over 25 years), collects examples of all of the above into semi-chronological and thematic groupings on the museum’s fourth floor. It’s a far less splashy show than we might expect from SFMOMA these days, and that comes as relief, especially when what one needs to take in Celmins’ work is ample time and space for looking.

Looking—really looking—at Celmins’ work isn’t a purely visual experience. Heater, one of her early pared-down paintings of objects in her 1960s Venice, California studio, puts an electric space heater in the center of a gray canvas. The only vibrant color comes from the orange glow at the heater’s center, so warm and matter-of-fact it half convinces viewers the image, too, must emanate heat.

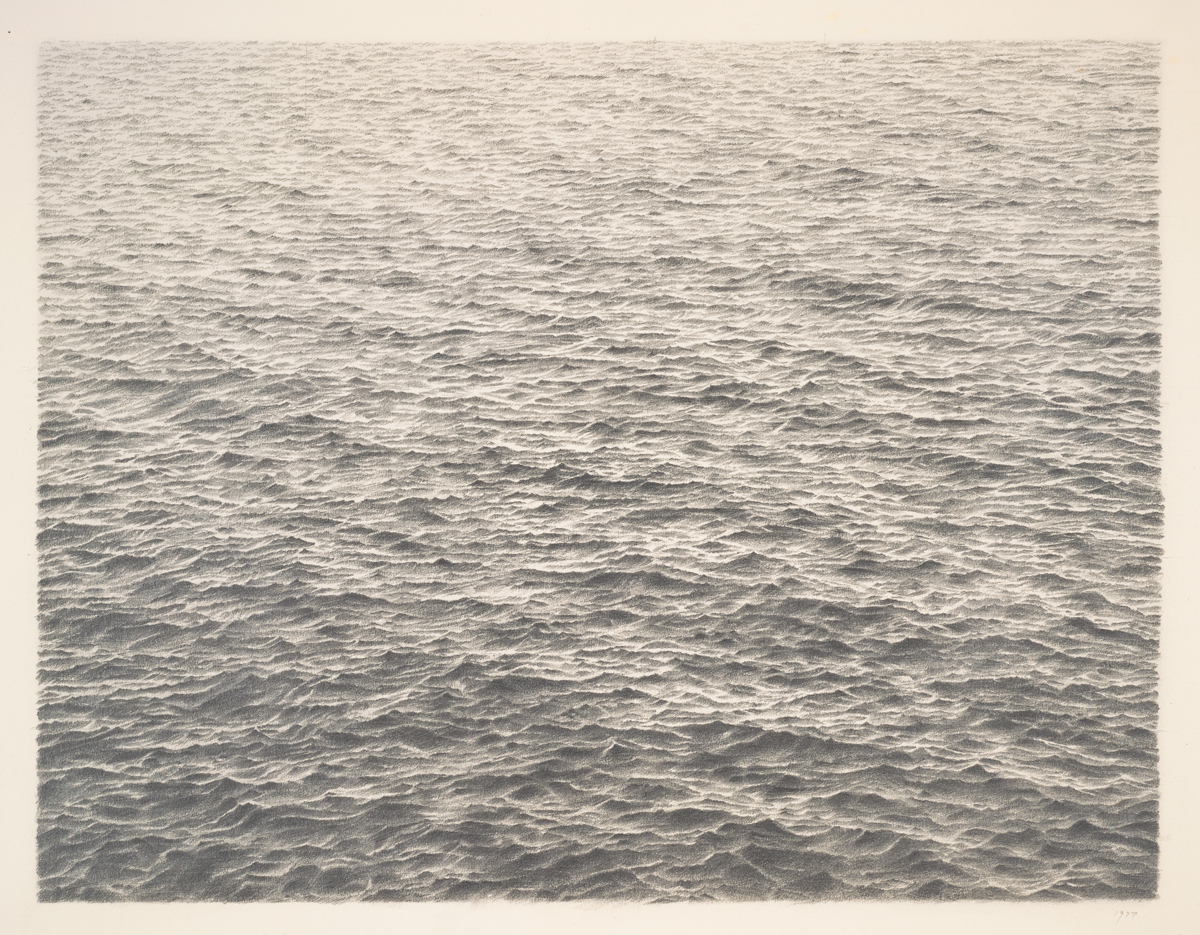

Elsewhere, in a gallery full of her ocean drawings, the repetition of graphite on paper, and Celmins’ precise gestures, threaten to lull viewers into a false supposition that once you’ve seen one ocean drawing, you’ve seen them all. That is, until Untitled (Ocean with Cross #1). By this time, the show has already trained viewers to stop and read any accompanying wall text for delicious details. (How else would you learn that Comb, her 75-inch-tall homage to René Magritte, was scaled to the height of Celmins’ then-husband?)