Growing up, Jeffrey Thomas Leong heard stories from his father, a Chinese immigrant who first traveled to San Francisco in 1920.

“Around the dinner table at night, he would tell us about his experiences growing up in China and coming to America,” says Leong, an East Bay poet and writer. “But he wouldn’t give us too much information. It would be little sketches.”

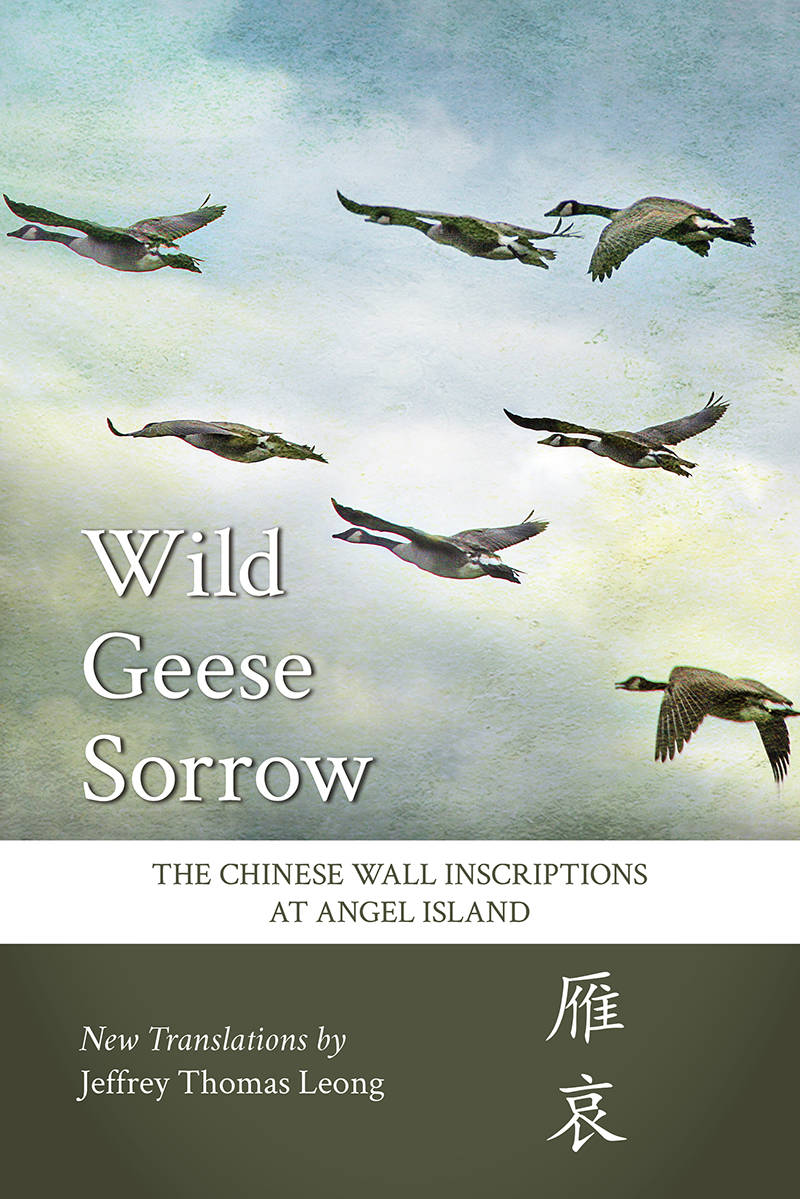

Those vague memories, which Leong recounts in the introduction to his book, Wild Geese Sorrow: The Chinese Wall Inscriptions at Angel Island, included his father’s journey through Angel Island, where he passed interrogations at the immigration station while his travel companion was denied entry and ultimately deported.

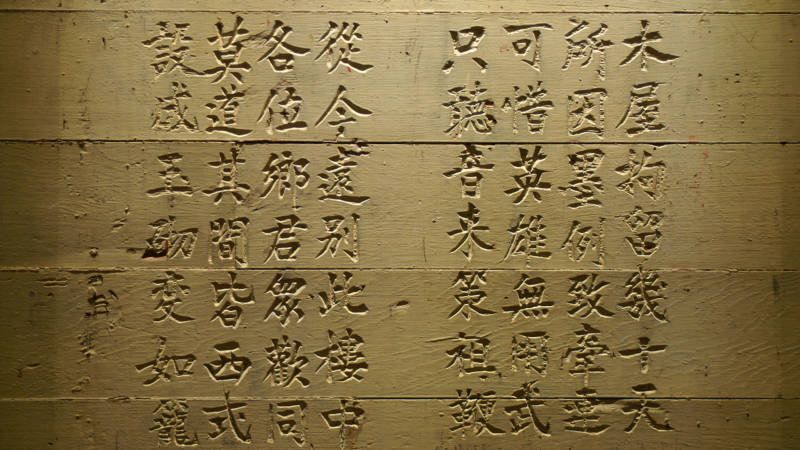

Imprisoned upon arrival, the Chinese immigrants etched their anguish, literally, into the walls. In the “wood house” at Angel Island, men carved poems into its surfaces, many of which were preserved by putty that immigration officials plastered, ironically, to erase the detainees’ efforts. The inscriptions—desperately chronicling heartbreak with a certain visceral immediacy—serve as a remarkable testimony of a Chinese immigrant experience that has largely been forgotten along with the larger history of Angel Island’s immigration station.

In Wild Geese Sorrow, Leong compiles 70 of the 200 or so identifiable poems written on the walls, including both the original text and his own translations.

Between 1910 and 1940, when the immigration station was active, the Chinese Exclusion Act was still in effect. It was the first U.S. law of its kind, banning immigrants of Chinese descent. At Angel Island, some 175,000 Chinese immigrants were processed as officials attempted to detect “paper sons” hoping to circumvent the racist law by fabricating relations to American-settled relatives. Few were ultimately deported, but countless were interrogated and detained indefinitely in wooden barracks.

Why is this history so seldom discussed? “There’s still that kind of attitude about Asian history not [being] as important as European history,” Leong says. The harsh realities of immigration were additionally kept quiet within families themselves, much like in Leong’s own, due to the “level of silence around the trauma of that experience,” he adds. “There is a lot that’s unknown and will never be known, especially because that generation, many have passed on and there are few remaining. Those stories are very precious.”

The detainees wrote mostly anonymously, describing hopeless despair, desperate financial circumstances and the injustice of American “barbarians.” Some engravings are deeply poetic in their literary imagery. Some are cruder expressions of anxiety and personal history. Others include cutting revelations about migration, such as this poem: “Since ancient times, leaving home results / in worthless change. / From expeditions, how many men ever return?” Another reads: “I am born unlucky, of Chinese descent, / So I must endure humiliation and contain hatred…”

These messages from the past, of course, feel deeply pertinent to the country’s current political and cultural battle surrounding immigration, though Leong says he could never have imagined contemporary U.S. policies hewing so closely to the island’s history.

“People ask me in readings, during Q&A—did they separate the children from their parents at Angel Island?” Leong says. “Because of what’s going on now, that’s a logical question. And I tell them, the answer is no. At Angel Island, young children went with the mothers, and the teenage boys had to go into the men’s barracks.”

The Trump administration’s recent family separations at the border are startling, but also only the continuation of an age-old reality. “Human beings who are put in a situation where they’re held against their will and have no idea what their fate will be is something as old as Angel Island and obviously older in human history,” he says.

Yet Wild Geese Sorrow does not stand solely as a relevant history lesson or as a remembrance of dehumanization and injustice. While the poems were carved in tragedy, they represent, for many detainees, the early memories of what often became a new life in America. Their words are a record of an immigrant community’s origins, rooted in perseverance in the face of daunting circumstances.

“The ultimate story I have to remind people: 95% of the people were able to land after their appeals and so on. Only about about 5% were deported. They are my parents, they are the forerunners of the Chinese American community,” Leong says. “They raised families and were successful, hard working people for the most part. That’s something to be proud of.”

Jeffrey Thomas Leong reads from Wild Geese Sorrow at Green Apple Books on Feb. 12. Details here.