The story of French artists Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore—neé Lucy Schwob and Suzanne Malherbe—is long and rich enough to fill multiple exhibitions, or multiple volumes.

But here’s the abridged version: They met as teenagers in 1909 and were inseparable until Cahun’s death in 1954. In the intervening years, Cahun and Moore moved to Paris, published books together, worked on experimental theater productions, participated in the Surrealist movement and staged political actions. Facing increasing anti-Semitism, they relocated to the island of Jersey in 1937, where they waged a two-woman propaganda war against Nazi occupying forces during World War II. They were arrested for their troubles, and sentenced to death by soldiers who couldn’t believe two middle-aged women were responsible for so much unrest. They were liberated, with the island, after spending a year in prison.

![Claude Cahun (Lucy Schwob) and Marcel Moore (Suzanne Malherbe), 'Untitled' [I am in training don't kiss me], 1927.](https://ww2.kqed.org/arts/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2019/02/04_ShowMe_Cahun_Moore_1200.jpg)

And throughout their relationship, they made art, a body of work “rediscovered” in the 1980s to fill an unknown gap in the lineage of queer, gender fluid, surrealist portraiture.

Show Me as I Want to Be Seen, the current group exhibition at the Contemporary Jewish Museum organized by assistant curator Natasha Matteson, uses Cahun and Moore’s collaborative photography as a jumping-off point to examine themes of identity (its performance, legibility and slippage) in the work of ten contemporary artists.

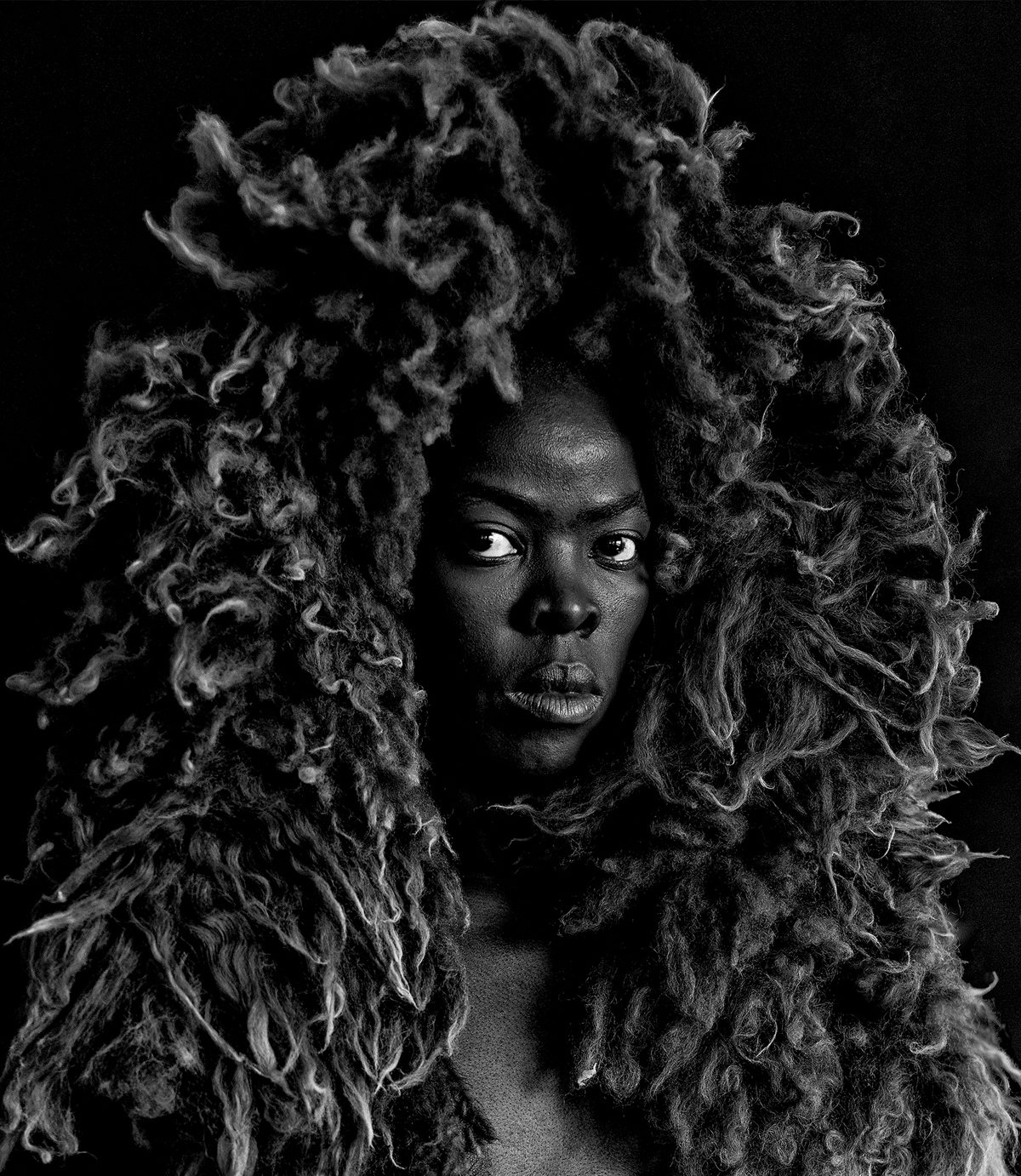

Of those, the clearest inheritor of Cahun and Moore’s subversive legacy appears in South African photographer Zanele Muholi’s staged self-portraits. In high contrast black-and-white gelatin silver prints, the artist poses in costumes fashioned from ordinary household objects—latex gloves, paper, a handbag—usually staring directly into the camera. Like the many photos of Cahun sporting theatrical makeup, Muholi darkens their skin in these images, a gesture of “reclaiming blackness” and forcibly confronting white supremacist notions of beauty. The results are striking.

While most of Muholi’s contemporaries in Show Me deploy images of bodies to some extent (the lone exception is Davina Semo’s sculptures, where the artwork titles carry the weight of personhood), some tread more closely to Cahun and Moore’s penchant for surrealism than portraiture.