“You may think you know everything there is to know about Monet,” teased curator Melissa Buron at the press preview for the de Young’s Monet: The Late Years, implying shocking, revelatory secrets to be learned within the subterranean depths of the museum’s special exhibition galleries.

Pshaw, I thought. While not everyone is an Impressionist scholar (that descriptor would be reserved for George Shackelford, deputy director of the Kimbell Art Museum and co-curator, with Buron, of the exhibition), c’mon, we all know Claude Monet. That is, in whatever way one can know an artist through thousands of reproductions of his or her most famous works—on mugs, T-shirts, coasters and, befitting our current local forecast, umbrellas.

But there’s a reason why the de Young is opening this Monet show just two years after the Legion of Honor hosted Monet: The Early Years, and it’s not solely because the museum knew it would bring in hordes of paying attendees. (As board president Dede Wilsey enthused during the press preview, “Anything Impressionist, and anything Monet,” she said, “just reeks of success.”)

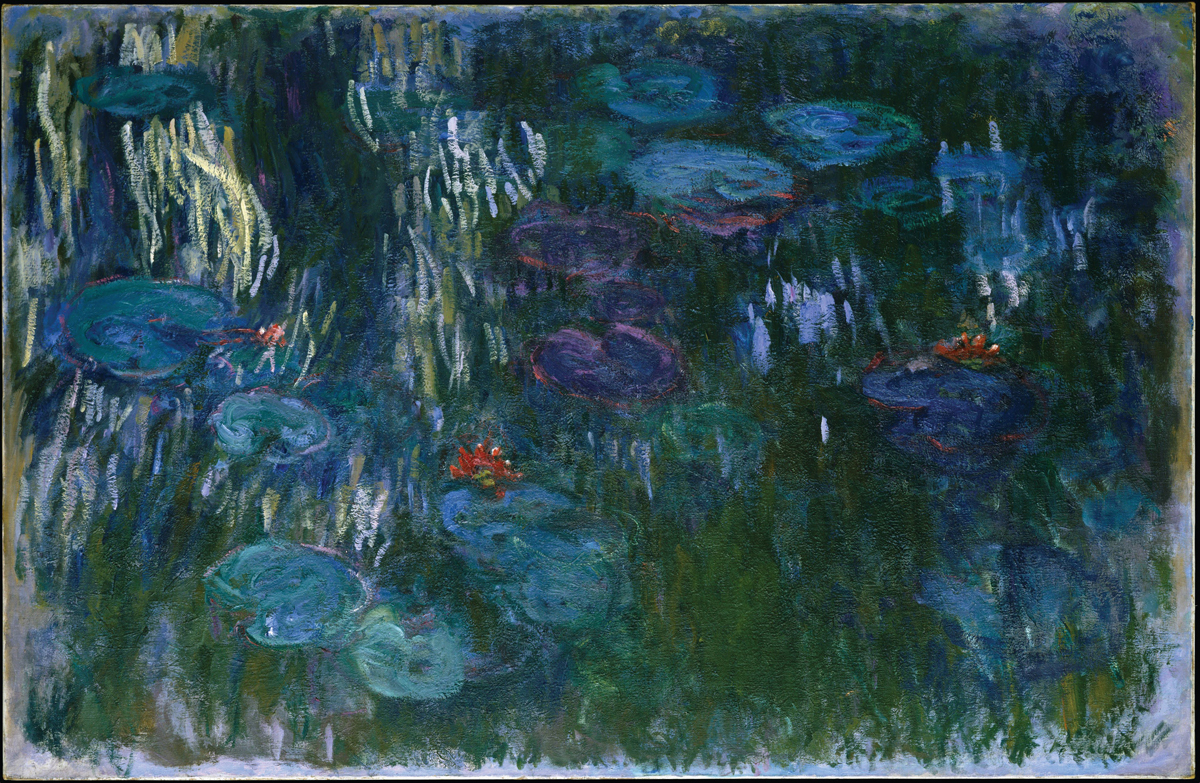

Simply put, seeing Monet’s paintings in person is exhilarating—especially because we think we know his work so well. Reproductions in books or on screens can’t capture his scintillating combinations of color, his buildup of oil paint on a canvas, the speed implied in his frenetic brushwork, or the vertiginous feeling of standing before a five-and-a-half-foot-tall painting and losing sense of which way is up.

The majority of the pieces on view at the de Young come from the final decade of Monet’s painting career, 1914 to 1924, when the French Impressionist was in his 70s and 80s (he died at age 86 in 1926). All were made in Giverny, at his bucolic residence in northern France surrounded by a meticulously maintained garden and man-made pond. As an introduction to “what we think we know,” the exhibition begins with a sampling of paintings from the late 1800s and early 1900s: images of the Seine, a Japanese footbridge, Monet’s beloved water lilies. By comparison, these canvases come to seem sedate and restrained in the rooms that follow.