It all started with a feeling.

The year was 1992, and Grateful Dead manager Danny Rifkin was driving a van past San Quentin State Prison with the Gyuto Monks. According to Grateful Dead publicist Dennis McNally, “The monks saw the building and said, ‘We sense a lot of pain over there.'”

When Rifkin told them it was a prison, they asked to pull over for a puja, or healing prayer. Rifkin later connected with prison chaplain Earl Smith to see about getting inside San Quentin, and he asked, “What’s the single best thing we can do?”

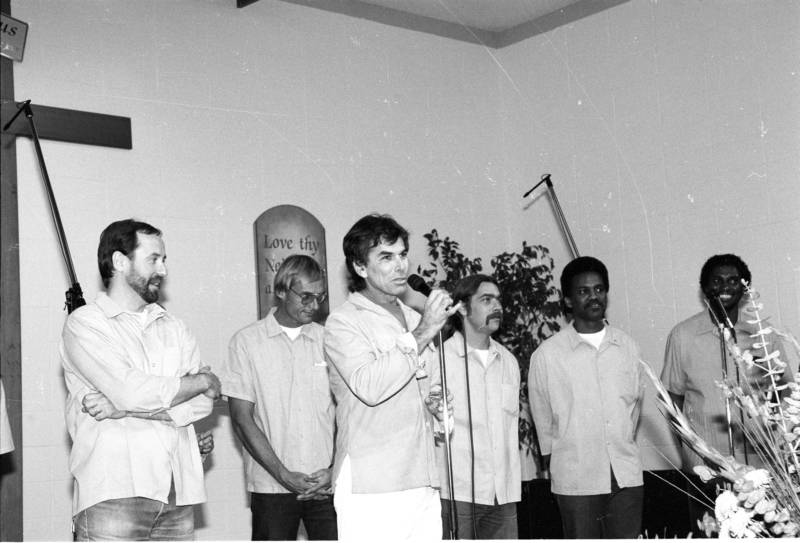

“And Earl said, ‘Convince these guys that they’re not here isolated for the rest of their lives, and that they still have a connection to the rest of the planet and society,'” McNally recalls. “Eventually, this led to Mickey Hart learning about their gospel choir.”

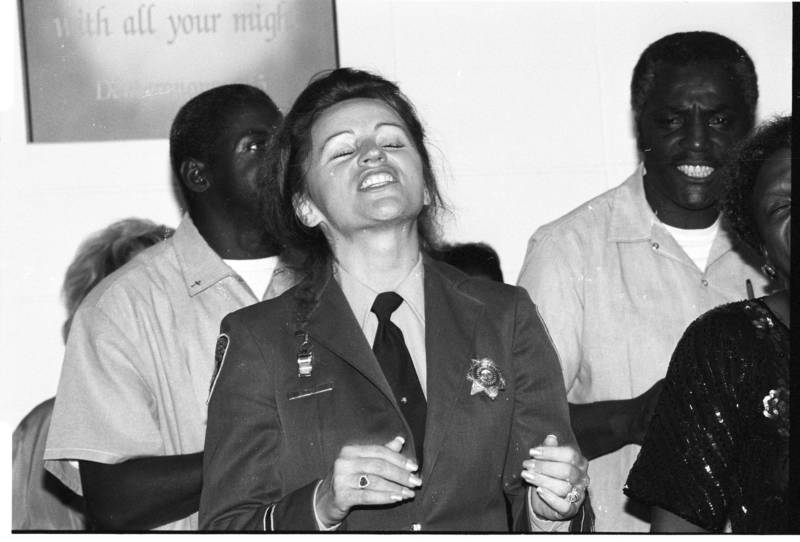

The resulting concert inside San Quentin is a key moment in Invisible Bars, a documentary by Bay Area filmmaker John Beck about the effect of prison on the families and children of the incarcerated. (It premieres on KQED TV on Tuesday, March 19, at 11 p.m.)