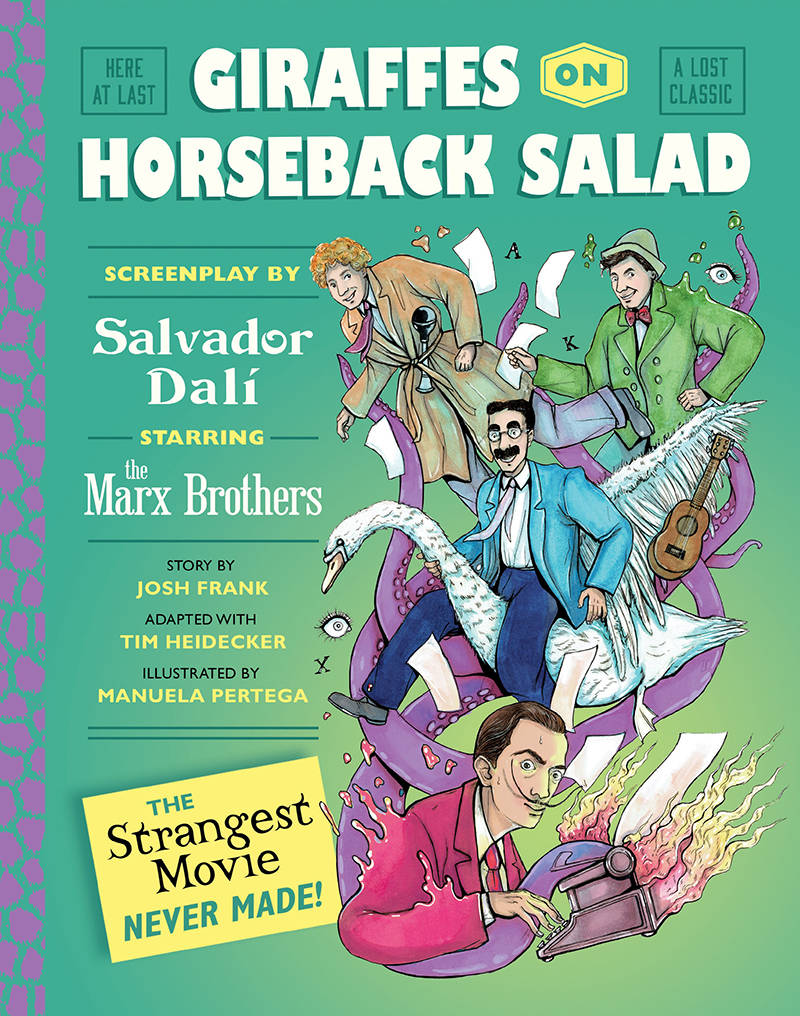

When Harpo Marx met Salvador Dalí, it was kismet, as Josh Frank reports in Giraffes on Horseback Salad, his diverting graphic novel about the pair’s 1937 attempt to collaborate on a movie of the same name. While it’s not too surprising that the troublemaking artist and the seditious comedian would be simpatico, their bond went deeper than that. They painted each other, and Dalí sent his new friend a full-size harp strung with barbed wire. Harpo replied with a photo of himself pretending to play the lethal harp, all his fingers wrapped in bandages. (It’s included in this book, courtesy of his son Bill.)

Of the two men, Dalí seems to have been the most infatuated. He wrote to André Breton, “I’m in Hollywood, where I’ve made contact with the three American surrealists: Harpo Marx, Disney and Cecil B. DeMille.”

So overcome was Dalí with Harpo’s genius that he wrote a treatment, and later an abbreviated screenplay, for a Marx Brothers movie to be called Giraffes on Horseback Salad. He and Harpo even pitched it to Louis B. Mayer. But as Frank puts it, “The meeting did not go well.” Among Dalí’s ideas: “Harpo opens an umbrella and a chicken explodes on all the onlookers. He … puts each piece [of chicken] carefully on a saddle that he uses as a plate, a saddle not for a horse, but for a giraffe!” The surrealist script fell flat even with Groucho Marx, who said simply, “It won’t play.”

Eighty years later, Dalí’s idea still won’t play. Even jazzed up with jokes by Tim Heidecker (a modern Marx Brother if there ever was one), Giraffes on Horseback Salad — the movie, not the book — is a baffling mess. Neither Dalí or Harpo seems to have realized that their approaches to humor were vastly different. The Marx Brothers’ work was acutely conscious of, and responsive to, established structures: They subverted the social order using its own rules. Groucho and Chico’s wordplay exemplifies this, and even Harpo’s silent antics acknowledged conventions in order to upend them.

Dalí, more often than not, simply headed off in a direction orthogonal to accepted reality. As a result, he’s not generally particularly funny at all. Some of his creations have a lightness — the spindly-legged elephants, his collaborations with designer Elsa Schiaparelli, his own kooky image — but usually his surrealism is deadly serious. That funk of portent permeates Giraffes on Horseback Salad like a vapor.