Though King became an icon of non-violence and peace, he also inwardly wrestled with anger and, at times, would snap at those he loved. Looking at how King dealt with anger reveals its dual nature—how it can be a motivating force for change, while also containing the potential for destruction.

When he was a young child, seeing his father’s anger had a real impact on King. Once, a white sales clerk told his father that they had to move to the back of a shoe store, rather than being waited on in the front of the shop. “Whereupon he took me by the hand and walked out of the store. This was the first time I had seen Dad so furious,” King later recalled, in a collection of writings called The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr.

“That experience revealed to me at a very early age that my father had not adjusted to the system, and he played a great part in shaping my conscience,” noted King.

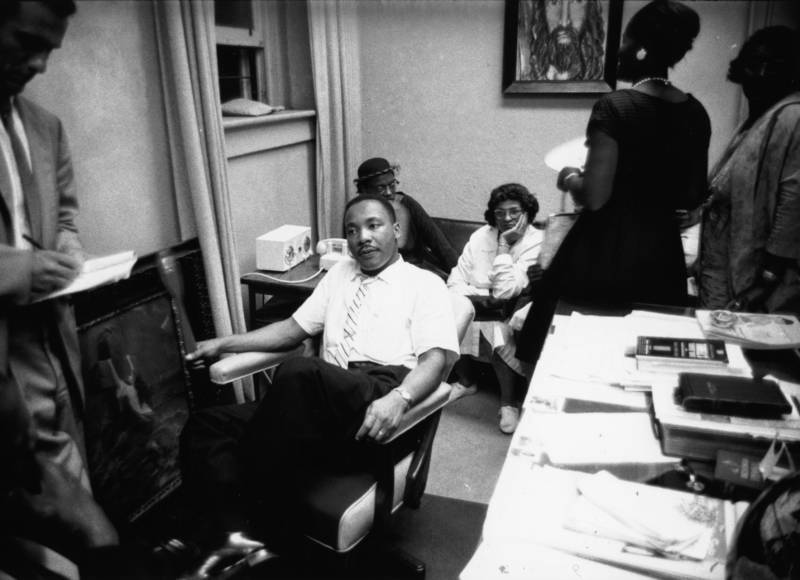

King was only 26 years old when he was thrust into a leadership role in the struggle for civil rights. Rosa Parks had just been arrested in Montgomery, Alabama, where King was working as a preacher. King found himself having to speak before thousands of people who had gathered in a mass meeting at the Holt Street Baptist Church—and those people were upset.

“How could I make a speech that would be militant enough to keep my people aroused to positive action and yet moderate enough to keep this fervor within controllable and Christian bounds?” King later wrote. “What could I say to keep them courageous and prepared for positive action and yet devoid of hate and resentment? Could the militant and the moderate be combined in a single speech?”

He told the crowd that the only weapon they would use was the weapon of protest—that they would follow the teachings of Jesus.

Their resolve was soon tested when someone threw dynamite at King’s house. He rushed home to find that a crowd of his supporters had gathered, and some had weapons. His wife, Coretta Scott King, later wrote in her book My Life, My Love, My Legacy that the atmosphere “was so rife with tension that if a black man had tripped over a white man, it could have set off a riot.”

King calmly stood on his front porch, told everyone to go home, and spoke about loving your enemies. “It was a really noble moment,” says David Garrow, a historian who wrote a biography of King. “Most people would be expressing very intense anger, and he was utterly to the contrary.”

In private, though, King struggled. He later recalled that that night, he lay awake in bed thinking that his wife and baby could have been killed by the blast. He wrote, “I could feel the anger rising.” But then he caught himself, and thought, “You must not allow yourself to become bitter.”

“He deeply believed in something that almost sounds silly, that almost sounds trite, but he really believed in the power of redemptive love,” says Clarence Jones, who worked as an attorney and speechwriter for King.

“From Dr. King’s standpoint, anger is part of a process that includes anger, forgiveness, redemption and love,” explains Jones. “Because if you only have anger, the anger will paralyze you. You cannot do anything constructive.”

In 1963, Jones went to see King in jail, in Birmingham, Alabama. Jones was hoping to talk about how to raise bail for the imprisoned protesters, but King was preoccupied with a full-page ad that he had seen in the local newspaper. It was an open letter written by the local white clergymen, and it said King should leave the city. It didn’t have a word about the injustice of segregation.

“So he was very angry,” recalls Jones.

King’s response, initially scribbled on the scraps of paper he had in his cell, is the famous Letter from a Birmingham Jail. His anger propelled him to write one of the most powerful pieces of persuasive writing ever. He passionately explained the principles of non-violent protest and the righteous, justifiable anger of African-Americans.

That’s not to say King never just showed irritation or snapped at people. He was, after all, human.

“Yes, he got angry with people he worked with. But the anger was in the context of respect and love,” says Jones. He says King’s anger was often more like a disappointment that people had misunderstood what his expectations were or weren’t meeting them.

Those episodes became more common in the last months of his life, after years of nonstop tension and work, says Garrow.

“There were a number of occasions where King expressed irritation at close friends and staff members,” says Garrow, noting that King was apparently depressed, exhausted, and drinking a lot.

King’s close companion, Ralph Abernathy, has written that on the day he was assassinated, King argued with a female friend, lost his temper, and knocked her across a hotel room bed.

“It was more of a shove than a real blow, but for a short man, Martin had a prodigious strength that always surprised me,” Abernathy wrote in his autobiography, And the Walls Came Tumbling Down. “She leapt up to fight back, and for a moment they were engaged in a full- blown fight, with Martin clearly winning. Then it was all over.”

Many found it shocking to think that King could be physically abusive to anyone, and Abernathy was widely criticized for telling this story.

In an interview with C-SPAN before he died, Abernathy said that King would have wanted him to be honest. “Jesus was a nonviolent personality,” noted Abernathy, “but Jesus became violent on one occasion when he ran the people out of the temple.”

Clayborne Carson, director of the Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University, says he doesn’t know if this account about King is true.

“But I do recognize that a Martin Luther King can be angry. It would surprise me if that were not the case,” says Carson. “I have no doubt that he got mad. There were many things for him to get mad at. He felt sometimes betrayed by other people. He felt the same kind of impatience that other people felt with the pace of change. All of these things would anger him.”

He says King learned how to use that anger productively. “You could be angry that the system that is oppressing you, but try not to direct that anger towards people who were caught up in that system,” says Carson.

During the bus boycott in Montgomery, for example, King did occasionally lose his cool with white officials—and quickly regretted it. “I was weighed down by a terrible sense of guilt, remembering that on two or three occasions I had allowed myself to become angry and indignant,” King wrote. “I had spoken hastily and resentfully. Yet I knew that this was no way to solve a problem…you must be willing to suffer the anger of the opponent, and yet not return anger.”

This, he knew, was not always easy. Later, after he had become famous,King had an advice column in Ebony magazine. Someone once asked, “How can I overcome my bad temper? When I am angry, I say things to those I love that hurt them terribly.”

King replied that the letter-writer had made an important first step by admitting this weakness. “You should also seek to concentrate on the higher virtue of calmness. You expel a lower vice by concentrating on a higher virtue,” King explained. “A destructive passion is harnessed by directing that same passion into constructive channels.”