Burgess Franklin Collins, better known as Jess, remains one of the more intriguing San Francisco artists to emerge from San Francisco’s post-war avant-garde. Much like his art, Jess was hermetic and slightly anachronistic in his tastes, eschewing prevailing aesthetic trends, and the art world altogether, to pursue a vision all his own.

Even his biography reads like one of the fairy tales he was fond of: giving up a career as a nuclear scientist because he wanted no role in bringing about the apocalypse, Jess enrolled in the California School for the Arts (now the San Francisco Art Institute) in 1949 to study painting and rekindle a childhood passion for art. A year later he met and became romantically involved with the poet Robert Duncan, adopting his new mononym. The two moved into a Mission Victorian where they remained life and creative partners for the next three decades, living happily ever after, as it were (Duncan died in 1988, Jess in 2004).

The continued allure of Jess is attested to by two ongoing exhibitions, Mythos, Psyche, Eros: Jess and California, at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and Secret Compartments at Anglim Gilbert Gallery. While the SFMOMA exhibition seeks to connect the dots between Jess and other California artists whose sensibilities and practices overlapped with his, the Anglim Gilbert show fills the gaps in the museum’s presentation, yielding a far more interesting depiction of Jess’ wide-ranging body of work.

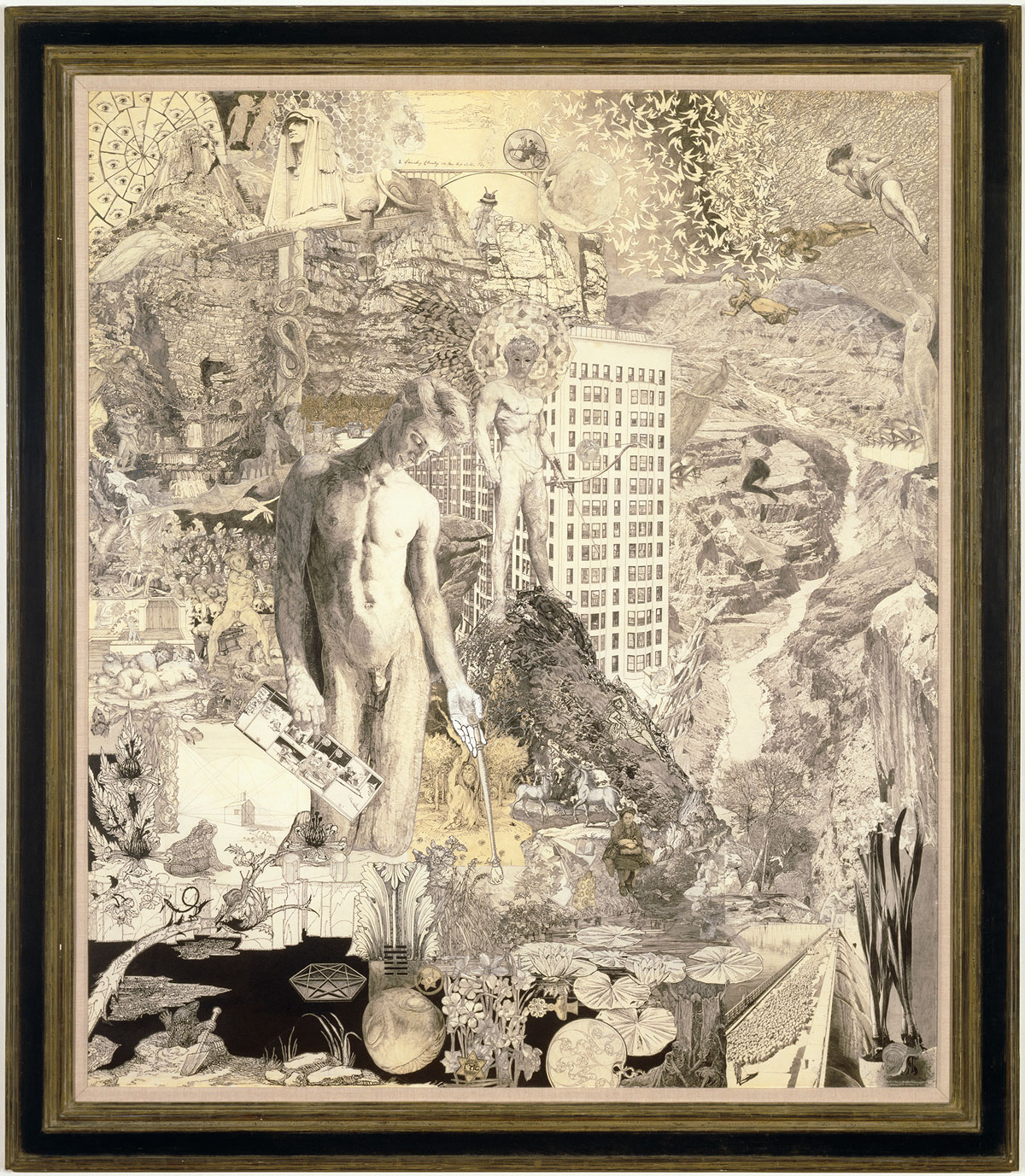

Jess preferred methods of making that began with existing images. Whether collaging delicate sprigs of printed matter into fantastic “paste-ups,” copying found images in a paint-by-numbers style for his “Translation” oils, or adding to and altering thrift store-sourced canvases, Jess’ métier was a kind of visual alchemy by which base materials became fantastic.

Whereas Dadaists used collage to critique modern life, and the Surrealists, after them, saw it as a means to open the floodgates of the unconscious, Jess’s approach to cutting and pasting was more self-contained, by turns whimsical and cabalistic. Much like Joseph Cornell and his shadow boxes, Jess’ assemblages, as he generally referred to his work, were indexes of his fascination with the outmoded and esoteric—Victoriana, children’s books, the occult—as much as they were tributes to his inner circle, Duncan especially.

Befitting someone whose favorite book was Finnegans Wake, Jess’s compositions are dense, riddled with literary and historical allusions. But they are also celebrations of surface—be it the gloppy residue of impasto, the delicacy of mass-reproduced engravings, or the sight of a naked man.