Marianne & Leonard: Words of Love, a warmly absorbing new documentary by British filmmaker Nick Broomfield, opens with an image of a beautiful young Norwegian woman steering a sailboat off the sun-soaked Greek island of Hydra. The footage, which was shot by famed documentarian and Broomfield mentor D.A. Pennebaker on a visit to the island in the 1960s, recurs from slightly different angles throughout the film. But Marianne Ihlen — an early lover of Leonard Cohen and the subject of several of his most famous songs including “So Long Marianne” — doesn’t steer this moving, sympathetic, but ultimately frustrating tribute. Perhaps inevitably, Cohen does, via Broomfield’s fascination with the singer’s tortured relations with the many women he romanced.

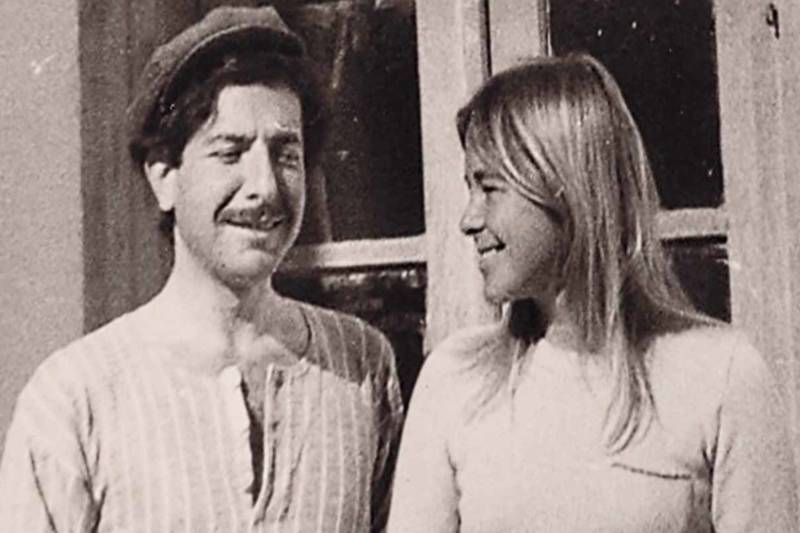

Ihlen and Cohen met in 1960 on Hydra, which at that time was forming as a hub of literary hippies with full subscriptions to the sexual revolution. The two had in common uncommon physical beauty and a sense of themselves as refugees, she from an abusive partner, he from the Orthodox Jewish family that both confined and inspired him. They became lovers, and Ihlen sustained Cohen through the writing of his early novel Beautiful Losers.

Juggling a deftly edited mix of footage, the voices of Cohen and Ihlen, and well-chosen testimony from friends of both, Broomfield covers the often excruciating bouts of parting and reconnecting that marked their relationship. Theirs was a love match, everyone agrees, but a brief one with a long tail of grief for Marianne, who repeatedly put her own life (and, tragically, that of her son Axel) on hold to be there for Cohen. Once he found his voice and his fortune as a singer, Marianne gradually got left behind, though he supported her financially, and their liaison sputtered on between Greece, Norway, Montreal and New York as Cohen got fully on board for free love.

With his trademark blithe disregard for the boundaries between narrative and non-fiction, Broomfield has cheerfully inserted himself into a bunch of impish but keenly observed and compassionate portraits of, respectively, Hollywood madam Heidi Fleiss, rocker Courtney Love, serial killer Aileen Wuornos and Sarah Palin. Depending on how you feel about his resolutely non-ideological approach, Marianne & Leonard is either the best thing he’s done or uncharacteristically circumspect, almost self-effacing. I say almost because Broomfield casually admits up front that he was, briefly, Marianne’s lover on Hydra, and the two remained friends until her death from leukemia in 2016.

The film is his least transgressive, but also most mature portrait of a woman who, by her own admission, suffered from crippling insecurities exacerbated by the claims to artistry of those she hung out with. Counterculture enclaves were rife with such women, and though Cohen waxes ecstatic onscreen about the movement’s gender parity, Broomfield (a bit of an Apollo in his youth too) gives the hippie moment its due while remaining admirably clear-eyed about the emotional wreckage and broken families that the sexual revolution left in its wake.

Marianne & Leonard founders, though, in sticking Ihlen within the vexing label of muse, which in its mostly male iteration functions as code for a passive beauty who makes the meals and clears the terrain, makes no demands and sits — in Marianne’s case, quite literally — at the feet of genius. (She’d have needed heroic reserves of forbearance to cope with choice cuts of early Cohen-speak like this one: “When I got up in the morning I had to decide whether I was in a state of grace.”) Genius, in return, is full of worship until the muse wears out her welcome. We see Marianne only through the attenuating fog of her beauty and her equable nature, where she languishes as a placeholder for all the women Cohen loved (or at least obsessed over) and left.

Late in life Cohen is heard regretting his own heedlessness. It’s not that Broomfield has cooked the books of Marianne’s history with Cohen. Indeed to the degree that he ever takes sides he’s with her and, probably correctly, identifies her as a somewhat tragic casualty. But though his focus keeps veering away to Cohen, he allows another woman, the vivacious and psychologically astute Aviva Layton (who was married to Cohen’s friend and fellow writer Irving Layton and knows the price of taking up with a congenital escape artist) to provide crucial insight into Marianne’s plight, as well as the reasons why she was so widely beloved of men and women alike. Layton is perceptive, too, about Cohen’s symbiotic bond with his intense mother, from whom he inherited a lifelong struggle with depression, and about her influence on his inability to sustain relationships with women.

As she lay dying in a hospital, Ihlen asked a friend to contact Cohen. Close to death himself, he wrote her a widely publicized letter of farewell, only this time minus the grandiloquence. “So Long, Marianne” is a beautiful melody, but willy-nilly, Broomfield’s sensitive tribute to its subject — and object — makes crystal-clear why it was never her favorite of his songs.