In 2005, Dax Pierson was on tour as keyboardist with Subtle, an Anticon Records-affiliated dance-punk-meets-hip-hop sextet, when tragedy struck. The band’s tour van slipped on black ice on a freeway in Iowa. After the car flipped upside down, Pierson’s seatbelt gave out, and he fell on his head.

The resulting injuries rendered Pierson partially paralyzed in all four limbs—including in his fingertips.

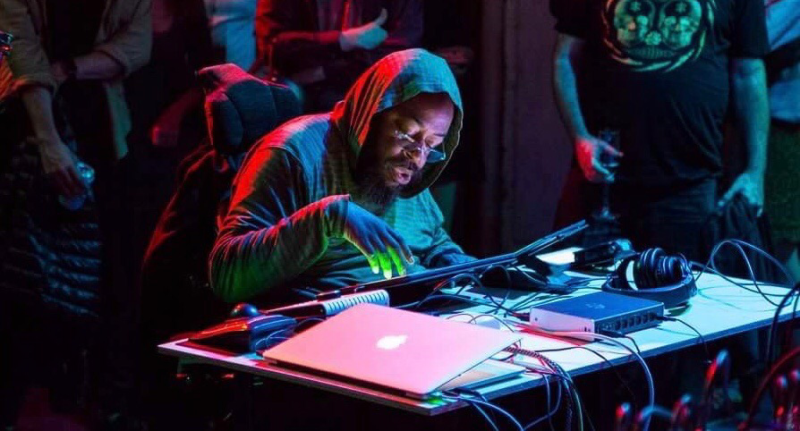

Now, 14 years later, Pierson has released his solo debut under his real name, and his first album in 11 years. Live in Oakland, out this month on Ratskin Records, introduces Pierson’s new style of freeform electronic compositions with a sprawling, ocean-like musical topography. With recordings of doctor’s visits and his wheelchair’s mechanical noise interspersed among droning synths and dramatic, reverb-heavy percussion, Pierson lets listeners into his recovery process, where the emotional challenges have sometimes been as heavy as the physical ones.

On the opening track, Pierson repeats the warning like a mantra: “Don’t take your physical abilities for granted. For you could lose them—at the snap of a neck.”