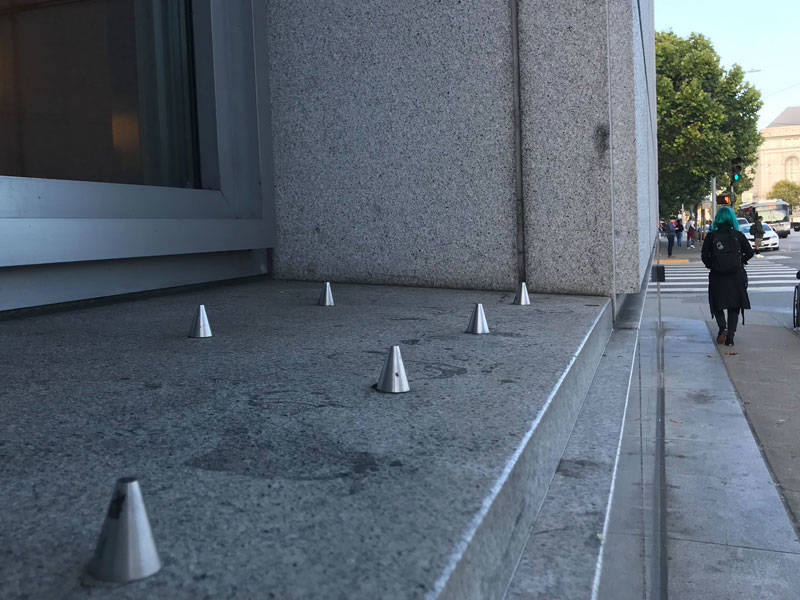

A city’s public architecture can tell you a lot about what it thinks of its citizens. Are the benches comfortable? Can I lay down here? Is there a place to sit while waiting for the bus? Urban planning provides tangible evidence of how a region grapples with some of its most pressing issues, whether that’s budget shortfalls or a crisis of livability.

Bay Area Rapid Transit is currently under fire for its pilot project aimed at preventing fare evaders from jumping through turnstiles with newly-installed modifications to gates at the Richmond and Fruitvale stations. The retrofitted gates, officially presented to BART’s board of directors as ‘Double-Decker’ and ‘Pop-Up’ modifications, have been derided as ‘skull-crushers‘ and ‘inverted guillotine’ gates by riders on Twitter.

“I haven’t seen anything that even comes close to the overt hostility of these inverted guillotine prototypes,” says Kurt Kohlstedt, digital director and producer for the architecture and design podcast 99% Invisible. “Usually they try to hide it better! I’ve encountered a lot of hostile design, but this one really takes the cake.”

In a viral tweet over the weekend, BART riders expressed their concerns over a recent fare-evasion modification pilot gate spotted at Fruitvale station. Many were quick to point out how the preventative effort is a disturbing example of anti-poor, anti-homeless and ableist design. Others called the prototypes an extreme example of hostile architecture.