In a one-room show on the San Francisco Museum of Art’s third floor, a “new to the collection” exhibition of framed Polaroids is actually new to just about everyone, a treasure trove of secret photographs that were almost lost to history.

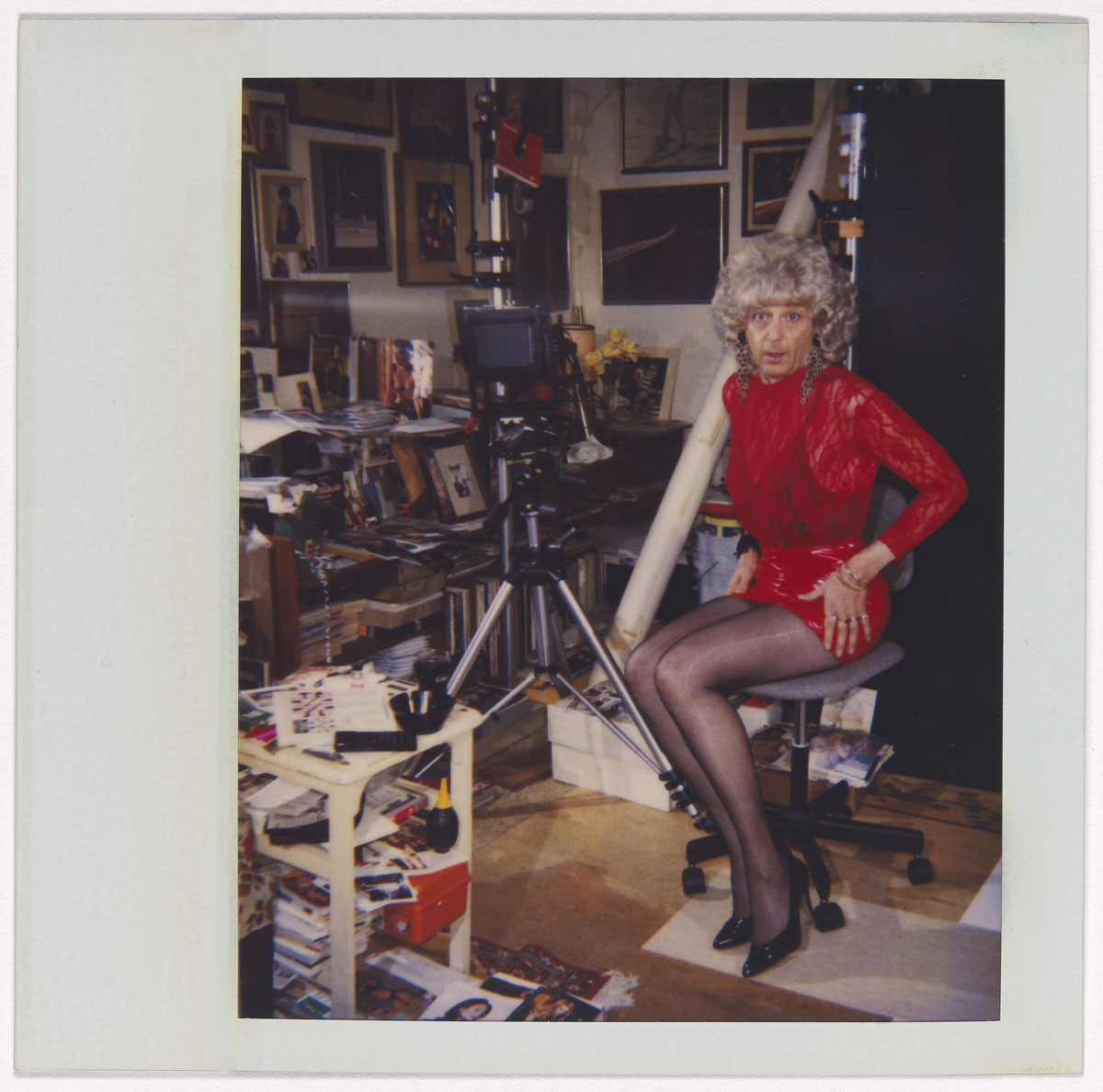

April Dawn Alison, curated by Erin O’Toole, presents a constellation of images on dark painted walls, images discovered after the death of an Oakland commercial photographer known to friends, family and neighbors as Alan Schaefer. Indoors, seemingly alone, Schaefer became someone else: April Dawn Alison, a feminine alter ego who, over the course of 30 years, photographed herself in playful poses and bondage scenarios. As contemplative and exuberant. Dressed up and stripped down.

Naming—and gendering—the artist responsible for the works in April Dawn Alison requires careful consideration. O’Toole opts for “she,” writing “the Polaroids are of April Dawn, by April Dawn.” In the accompanying catalog from London publisher Mack, Hilton Als’ essay employs a more fluid use of both pronouns: “April was a maker and so was the guy who made April; these pictures are a record of a double consciousness, the he who wants to be a she and the she who is a model and photographer.” Zackary Drucker’s writing ties the work to a long lineage of trans artists and performers, using “she” throughout.

An equal amount of consideration went into the decision of whether or not to present these images publicly at all. Schaefer passed away at age 67 in 2008. O’Toole edited April Dawn Alison down from 9,200 Polaroids, a collection that remained remarkably intact while an estate liquidator sold off the rest of the artist’s belongings piecemeal. San Francisco painter Andrew Masullo purchased (or better put, rescued) the collection from the liquidator, gifting it to SFMOMA in 2017.

O’Toole writes about discussing issues of privacy and intent with the artist’s friends and family, concluding: “I have come to believe that the deep humanity, emotional impact, and visual sophistication of these photographs demands that they be shared.” It’s rare to see a curatorial statement dip into first person, let alone acknowledge any moral quandaries the organizer might have experienced in the process of putting together a show.

In the case of April Dawn Alison, this honesty and openness is fitting. Alison shot the intimate Polaroids in the tight quarters of a living space that appears increasingly filled with photography equipment, framed images, fashion ads and stacked storage boxes as time progresses. The images are incredibly vulnerable, even as she makes a silly face for the camera, widening her eyes in mock surprise or sticking out her tongue.