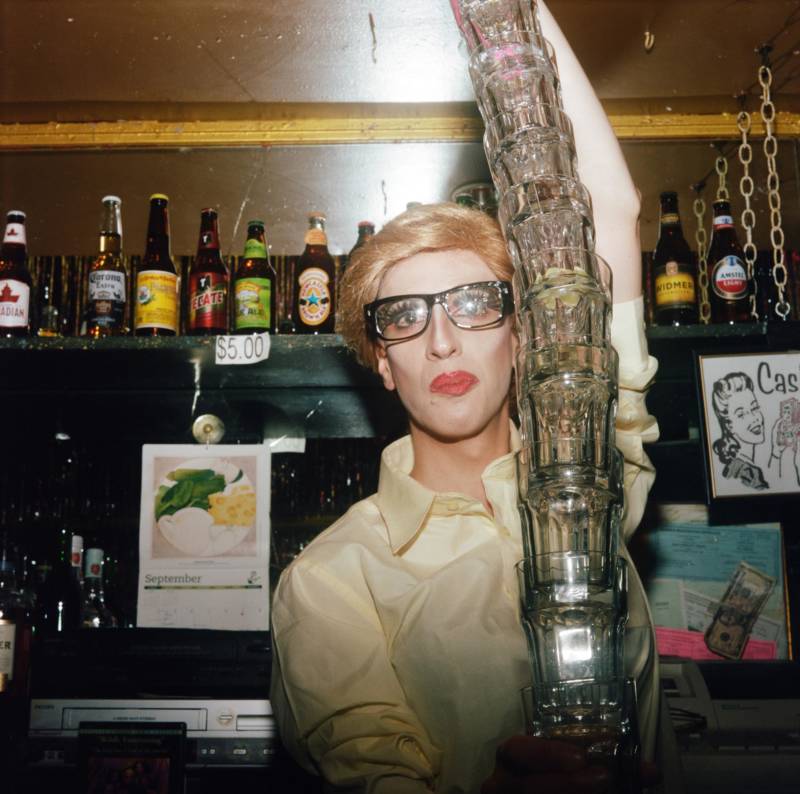

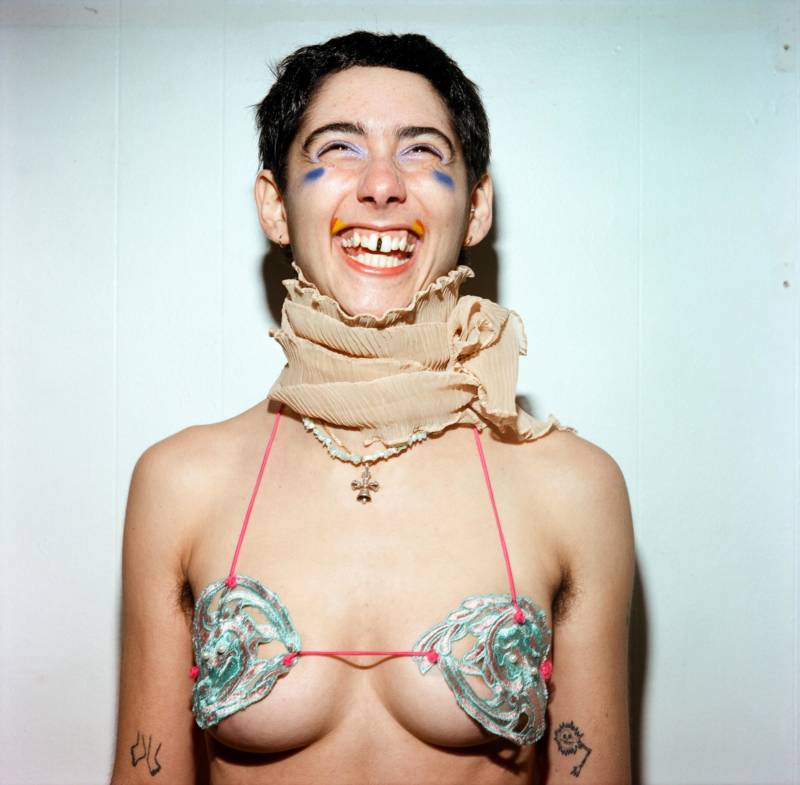

In 2012 Marissa Patrice Leitman started going to Aunt Charlie’s, a narrow hallway of a bar in the Tenderloin district, for High Fantasy, the lawless, now-defunct Tuesday drag night, with a hulking film camera and a long flash cord. Her documentation of the neighborhood’s last working-class gay bar in the years since shows intimate, sustained attention to a site of revelry and tenderness, release and hurt. The freelance photographer and cofounding director of artist-run performance space Hit Gallery developed a style in tandem with her deepening relationship to the bar’s community, showing how the boundaries between audience and performer eroded in riotous and sometimes subtle collective acts of self-discovery.

The pictures, some of which recently appeared in a book published by Nighted Life, compose There Will Always Be Roses in San Francisco, the latest in a series of Aunt Charlie’s-themed exhibitions at the Tenderloin Museum. Ahead of the show, which opens Thursday, Oct. 3 and runs through Sunday, Nov. 3, Leitman reflected on photographing the High Fantasy drag scene, and how it changed her own life. The conversation has been edited for concision and clarity.

Can you tell me about your introduction to Aunt Charlie’s?

It was in a stalker way: I knew about it before I moved to San Francisco from musicians and drag performers. On my first night, Colin Self performed. Sometimes it’s dead-ass empty, only old regulars. Other times people are slammed against the railing—it was one of those nights.

How did your first impression live up to your preconceived notion of the place?

It was ten times smaller than I thought, but it met the rest of my expectations. I was totally mystified. It had this esteem, my idea was of a cool, beautiful, glamorous place, and it is that.

You didn’t start going for a photography project. What attracted you to the community?

At first it was the façade, everybody acted like a celebrity. Whether or not they had much materially to show, they had the attitude. Later I liked how they would also just let you be. As glamorous and grandiose as it might be, it also has a familial, humble vibe. That comes from the bar historically—it’s the oldest gay bar in the Tenderloin, people there lived through AIDS.

High Fantasy specifically has traditional, older queens and also younger queens. There’s shade and arguments but not much judgment about whether one generation is better. And there’s drag kings and women who perform as drag queens. There’s no rules and everybody’s interacting. … At the last one, I thought, “If there was an earthquake that’d be fine, I could die here.”

How did you earn the trust of the people you photographed?

I have photography ethics that drive me crazy—I won’t take pictures of people I don’t know. I went to a drag show last night in L.A. to see my friend, and I was getting stink-eye from people who thought I was being pretentious by refusing to take their picture. I’m trying to break some of these rules. I take pictures out of admiration—determining or admitting what I’m attracted to.

You have a conspicuous camera.

I purposefully use really big cameras. It’s a Mamiya C330 that makes me look like a steampunk or some kind of Victorian fetishist. It has an extended flash cord, like 20 feet long. I’m not very graceful with it either. I’m stumbling around with this giant cord wrapped around my neck.

In this setting some people are excited by the camera, right?

It’s a drag bar so there’s no shortage of vanity, and over time people become comfortable with the object, it has more presence than a point-and-shoot, a ritualistic way of presenting itself.