Staff at Mills College are following in the footsteps of the Oakland liberal arts institution’s adjunct faculty members by unionizing as part of a broader organized labor trend in Bay Area higher education.

Staff at Mills College, Recovering From Budget Crisis, Follow Faculty in Union Campaign

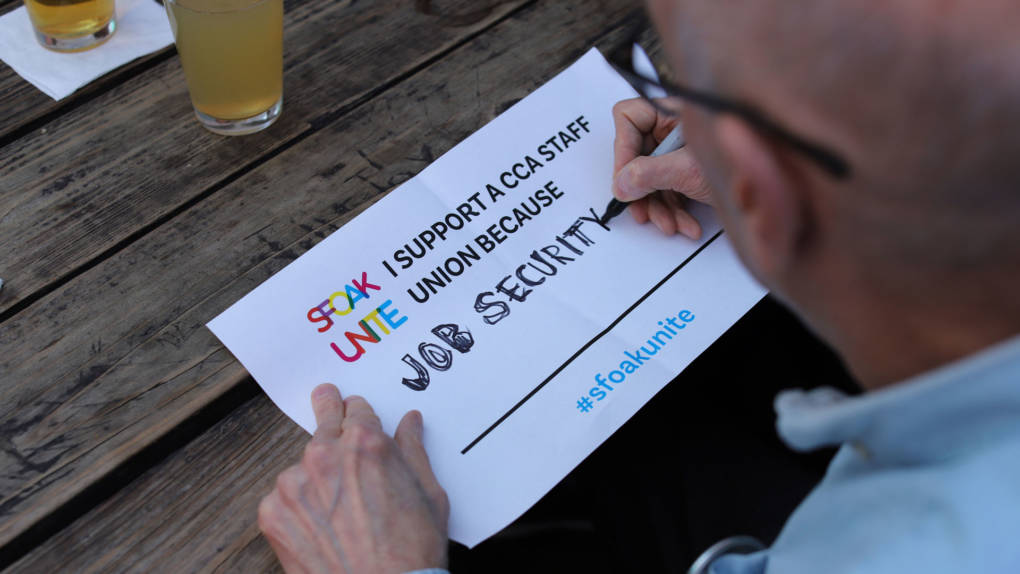

Last month Mills staff announced the campaign to unionize with Service Employees International Union (SEIU) Local 1021, which also represents Mills faculty and this year organized staff at California College of the Arts. Organizers say the effort has widespread support on campus and estimated more than 200 employees are eligible for the bargaining unit.

On Thursday, members of the staff organizing committee, joined by a student supporter, delivered a letter to Elizabeth Hillman, the school’s president, requesting the administration voluntarily recognize the union in order to avoid a costly, potentially contentious election process through the National Labor Relations Board. “We seek to cultivate a partnership with College administration that honors the overwhelming support for unionization among Mills staff,” it reads.

“When it comes to labor unions, Mills embraces the democratic principle of free and fair decision-making by employees,” said Hillman, who’s led Mills since 2016, in a statement to KQED. “We’re now assessing how the possibility of unionization would affect our efforts to work together with our faculty and the entire community to ensure a sustainable future for Mills.”

Workers in various departments say they’re organizing for higher wages, stronger benefits and greater representation in institutional decision-making as Mills rebounds from a “financial emergency” two years ago. Like faculty and staff at other local colleges to unionize in recent years, they’re motivated to address issues such as wage stagnation, with incoming employees earning more than longtime ones in similar roles, by the rising cost-of-living in the Bay Area.

“Mills has a social-justice and diversity policy that’s public and is supposed to drive institutional decisions around staffing and pedagogy,” said Brendan Glasson, a 2018 Mills graduate and staff organizer who now works as the music center technical director. “This is about helping Mills adhere itself further to its commitments to equity and sustainable working conditions.”

Some Mills staff have gone as many as eight years without raises, and benefits such as retirement contributions have declined as well, according to staff organizers. Employees have also been laid off and then encouraged to reapply for similar positions with added responsibilities. For example, Madison Davis, an alum and staff organizer who’s worked as a Mills fundraiser since 2017, said her job was previously divided between two people.

Due to the working conditions and low morale, Mills struggles with employee retention, and union organizers point out that rapid staff turnover also diminishes the student experience. “As a longtime employee, I’m watching Mills become a place where people work for 2-5 years and then leave, and that’s not particularly sustainable for us or our students,” said Vala Burnett, a Mills alum and staff organizer who’s worked as a health-sciences coordinator since 2005.

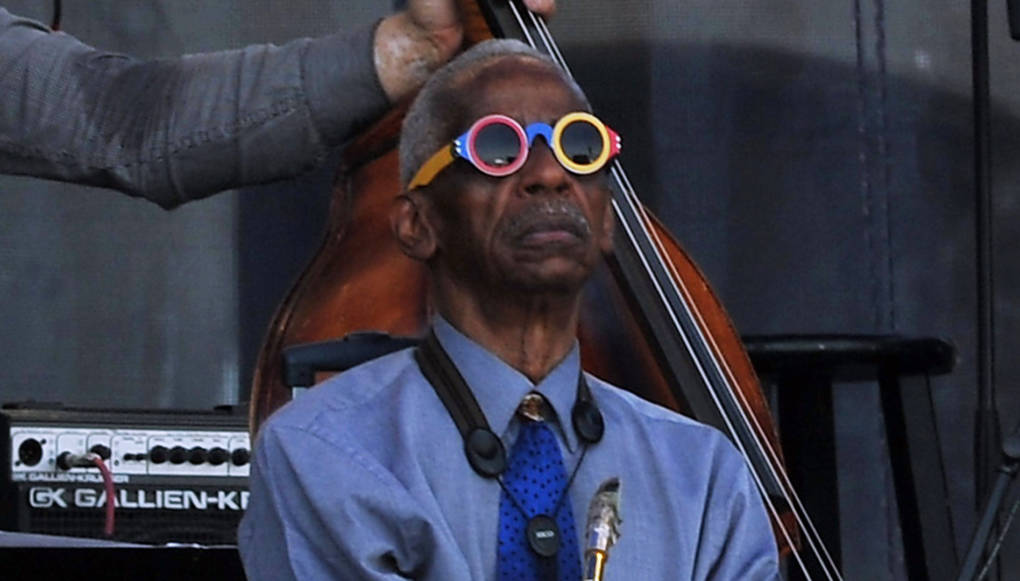

Mills, a private college for women and gender non-binary students, with graduate programs for all genders, declared a financial emergency in 2017 to resolve a $9 million deficit, and moved to fire eleven professors, many of them tenured, including the internationally renowned composer and improviser Roscoe Mitchell. The American Association of University Professors criticized the administration for “declining to consider … alternatives to terminating faculty appointments.”

Beyond forcing out Mitchell, an important draw for music students, the crisis dramatically affected the storied Center for Contemporary Music: Co-directors Chris Brown and Maggi Payne, longtime campus and music scene fixtures, retired early in the hopes of pre-empting additional cuts. Several other departments were also marked for downsizing as the school struggled to increase enrollment and, in the view of critics, prioritized sciences over liberal arts.

“Like many other small colleges, we are continuing to manage a budget deficit created by investment in new programs and lower enrollments,” Hillman said in a statement.

In the wake of the restructuring—part of a financial stabilization plan aiming to balance the budget by next year—Mills staff believe unionizing will give them greater representation in cost-cutting decisions in order to avoid or mitigate the effects of similar layoffs. “So it’s also about transparency,” Burnett said. “Through this process we get to the table, we get to open the books, and then staff is positioned to bring our knowledge to help Mills solve its problems.”

SEIU Local 1021, which represents staff and faculty at several local private colleges, helped Mills adjuncts ratify their first union contract in 2016. According to the union, the contract provided adjuncts with an average 13-percent raise, protection against reduction of benefits and more say in working conditions. SEIU, known for representing public employees, has been organizing adjunct professors in recent years as part of its “Faculty Forward” campaign.